Didda

Didda (958 - 1003 AD) was ruler of Kashmir from 958 AD to 1003 AD, first as a Regent for her son and various grandsons, and thereafter as sole ruler in her own right. The contemporary information about her rule is almost nil and meagre references relating to her are obtained from the Rajatarangini, a work written by Kalhana in the twelfth century.

Contents

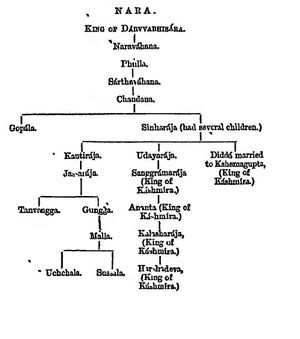

Didda in the Genealogy of Nara

Rajatarangini[1] provides us following Genealogy of Nara:

Formerly at Darvvabhisara there lived a king named Nara of the Gotra of Bharadvaja, who had a son named Naravahana, and Naravahana had a son named Phulla. Phulla had a son named Sarthavahana, his son was Chandana, and Chandana had two sons, Gopala and Sinharaja, Sinharaja had several children, his daughter Didda was married to Kshemagupta. Didda made Sanggramaraja (son of her brother Udayaraja) king. She had another brother, Kantiraja, and he had a son named Jassaraja, Sanggramaraja had a son named Ananta, while of Jassaraja were born Tanvangga and Gungga. Ananta's son was Kalasharaja, and of Gungga was born Malla. Kalasha's son is king Harshadeva, and Malla's sons were Uchchala and Sussala.

Clan of Didda

Didda was a daughter of Simharāja, the king of Lohara, and a granddaughter of Bhima Shahi, one of the Hindu Shahi of Kabul. Lohara lay in the Pir Panjal range of mountains, on a trade route between western Punjab and Kashmir.[2][3]

Marriage

She married the king of Kashmir, Ksemagupta, thus uniting the kingdom of Lohara with that of her husband.

History

When Ksemagupta died following a fever contracted after a hunt in 958, he was succeeded by his son, Abhimanyu II. As Abhimanyu was still a child, Didda acted as Regent and effectively exercised sole power.[4] Compared to other societies of the period, women in Kashmir were held in high regard[5] Even prior to becoming Regent Didda had considerable influence in state affairs, and coins have been found which appear to show both her name and that of Ksemagupta.[6] With Rudrama Devi of the Kakatiya dynasty, she is one of the very few queens in Indian history.[7]

Her first task was to rid herself of troublesome ministers and nobles, whom she drove from office only to have them rebel against her. The situation was tense and she came close to losing control, but having asserted her position with support from others, including some whom she bribed, Didda displayed a ruthlessness in executing not only the rebels who had been captured but also their families. Further trouble erupted in 972 when Abhimanyu died. He was succeeded by his son, Nandigupta, still a young child himself, and this caused restlessness among the Dāmaras, who were feudatory landlords and later to cause huge problems for the Lohara dynasty which Didda founded.[8]

In 973 she "disposed of" Nandigupta, in Stein's phrase, and then did the same to Tribhuvanagupta, his younger brother, in 975. This left her youngest grandson, Bhimagupta, on the throne, again with Didda as Regent. Her desire for absolute power became untrammeled, especially after the death of Phalunga, a counsellor who had been prime minister of her husband before being exiled by Didda after Ksemagupta's death and then brought back into her fold when his skills were required.

She also took a lover called Tunga at this time and although he was a mere herdsman this provided her with a sense of security sufficient that in 980 she arranged for Bhimagupta to be tortured to death and assumed unfettered control for herself, with Tunga as her prime minister.[9] Although there remained some discontent among the Dāmaras, Didda and Tunga were able to resolve the issues by force and by diplomacy, causing Stein to comment that

The statesmanlike instinct and political ability which we must ascribe to Didda in spite of all the defects of her character, are attested by the fact that she remained to the last in peaceful possession of the Kashmir throne, and was able to bequeath it to her family in undisputed possession.[10]

She adopted a nephew, Samgrāmarāja, to be her heir in Kashmir but left the rule of Lohara to Vigraharāja, who was either another nephew or perhaps one of her brothers. From this decision arose the Lohara dynasty of Kashmir, although Vigraharāja even during her lifetime made attempts to assert his right to that area as well as Lohara.[11][12]

In Rajatarangini

According to Rajatarangini[13] The queen of Kashmir Didda was excessively grieved at the death of her son Abhimanyu whose infant son Nandigupta became king. For a short time, the queen, remained sunk in grief and did not exercise much cruelty. And from that time she became religious. The superintendent of the city, named Bhuyya, brother of Sindhu, and a good man, was her adviser in her pious deeds. She was how once more loved by all, because of her affection towards her subjects. Ministers who allay the cruelty of their sovereigns are scarce. For the benefit; of her dead son, the queen built a town, named Abhimanyupura, and an image of a god, named Abhimanyusvami. She then went to Diddapura and set up a god Diddāavami, and a temple for the convenience of travellers from the interior of the country. For the benefit of her dead husband, she built Kangkanapura, and there set up an image of another god (Vishnu) of white stone which was also called Diddāsvāmi. She also built a large house (a sarai) for the Kashmirians and for her own countrymen (the People of Lohara.) She set up a god named Sinoasvami after her father's name, and built a house far the dwelling of tho Brahmanas of her country. At the junction of the Vitasta and the Sindhu River, she built temples and houses of gods, and made the place holy. She built in all sixty-four images of gods. She repaired the part of the city, which was injured by fire ; and built stone walls to the temples.

In the Kashmirian Era 89 in the month of Vādra, on the eighth bright lunar day, the queen died, and the Yuvarija Sanggramaraja became king. [14]

Rajatarangini[15] tells that ....Didda, among the wives of kings and Sussalā, among the wives of ministers, reached the utmost perfection of virtue by setting up various religious establishments. Sussalā built the matha of Shrichankuna of stone which till then had existed only in name. (p.216)

Rajatarangini[16] tells ....A certain Brahmana who had some money revived him to life; and thinking that Asamati was a relative of Didda, the daughter of Sahi, he brought Bhikshachara to Didda, and wily Didda, took him and sent him to another country and there in the south he lived privately. When Naravarmma, king of Malava came to know who he was, he instructed him in learning and in arms as his own son. Some say that Jayamati saved Bhikshachara by destroying another boy like him, and of his age. When the king learnt, through his spies that Bhikshachara had returned from foreign countries, his affection towards Jayamati began to abate. But the patient king without disclosing his designs concluded terms with the kings through whose territories Bhikshachara was to come to prevent his entrance into Kashmira. Foolish people who do not hide their jealousy for women or their fear of their enemies are imposed upon by others. Some again say, that after Bhikshachara had been killed, Didda brought a boy like him and caused him to be known by Bhikshachara's name. This report whether true or false was widely believed, and even gods did not suppress the belief. Such facts are more wonderful than what is dreamt in dreams or seen in magic or illusions. The king secretly planned to destroy this man. (p.20-21)

Jat History

Bhim Singh Dahiya[17] has described about the history of Lohara clan. This clan is famous in Kashmir history and gave it a whole dynasty called Lohar dynasty. Their settlement in India was Loharin, in Pir Pantsal range. The Lohar Kot-fort of Lohars is named after them. The famous queen Dida, married to Kshemagupta, was daughter of Lohar Kong Simha Raja, who himself was married to a daughter of Lalli (Jat Clan) Sahi king Bhima of Kabul and Udabhanda (Und, near modern Attock).

Rajatarangini[18] tells that Kshemagupta, King of Kashmir, bestowed thirty-six villages which were attached to the several monasteries that were burnt, to the lord of Khasa. Sinharaja, governor of fort Lohara, married his daughter to the king. This girl's name was Didda, and her mother's father was the Shahi.

Thus Didda was a Lohariya Jat scion, and a granddaughter of Lalli Jats of Kabul baseless called Brahmans. The descendants of their ruling family are still called Sahi Jats.

Queen Didda, made one Sangram Raj, her successor. He was the son of her brother Udaya Raj and he died on 1028 A.D. [19] Lohar itself remained with Vigrah Raj. [20]

Bhim Singh Dahiya writes that another Jat, named Chankuna (चणकुण), of Tokhara clan, was chief minister of Lalitaditya. Why all these Jats were holding predominant positions unless the rulers themselves were Jats of Lohar and other clans? [21]

According to Bhim Singh Dahiya[22] the Gondal clan represents the “Go-nanda” dynasty of Kashmir, the Lohar jats are the descendants of the Lohar kings of Kashmir, just as the Lalli, the Sahi, the Balhara, the Bring, the Takhar, the Dhonchak, the Samil, the Kular, and so on represent the people mentioned in the Rajatarangini of Kalhana.

References

- ↑ Rajatarangini of Kalhana:Kings of Kashmira/Book VII (i), pp. 266-267

- ↑ Stein, Mark Aurel (1989b) [1900], Kalhana's Rajatarangini: a chronicle of the kings of Kasmir, Volume 2 (Reprinted ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0370-1, pp. 293-294

- ↑ Stein (1989a), p. 104

- ↑ Stein (1989a), p. 105

- ↑ Kaw, M. K. (2004), Kashmir and it's people: studies in the evolution of Kashmiri society, APH Publishing, ISBN 978-81-7648-537-1, p. 91

- ↑ Ganguly, Dilip Kumar (1979), Aspects of ancient Indian administration, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-098-3, pp. 68-69

- ↑ Kalia, Ravi (1994), Bhubaneswar: From a Temple Town to a Capital City, Southern Illinois University Press – via Questia, p. 21

- ↑ Stein (1989a), p. 105

- ↑ Stein (1989a), p. 105

- ↑ Stein (1989a), p. 106

- ↑ Stein (1989a), p. 106

- ↑ Stein (1989b), p. 294

- ↑ Rajatarangini of Kalhana:Kings of Kashmira/Book VI,p.162-163

- ↑ Rajatarangini of Kalhana:Kings of Kashmira/Book VI,p.167

- ↑ Kings of Kashmira Vol 2 (Rajatarangini of Kalhana)/Book VIII (i) ,p.216

- ↑ Kings of Kashmira Vol 2 (Rajatarangini of Kalhana)/Book VIII,p.20-21

- ↑ Jats the Ancient Rulers (A clan study)/Jat Clan in India,p. 263

- ↑ Rajatarangini of Kalhana:Kings of Kashmira/Book VI,p.154

- ↑ RAJAT, VI, 355 and VII, 1284

- ↑ For details see, RAJAT, Vol II, p. 293; Steins note. E

- ↑ Jats the Ancient Rulers (A clan study)/Harsha Vardhana : Linkage and Identity,p.225

- ↑ Jats the Ancient Rulers (A clan study)/Introduction,p.xi

Back to Jat Ranis