Ghosondi

Ghosondi (घोसोंड़ी) or Ghosundi (घोसुन्डी) is a village in Chittorgarh tahsil in Chittorgarh district in Rajasthan.

Contents

Variants

- Ghosundi घोसुंडी (म.प्र.) (AS, p.313)

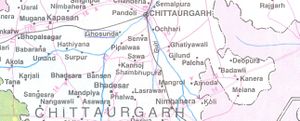

Location

Jat clans

Gajraj (गजराज) Gajrania (गजरनिया) Gajraniya (गजरनियाँ) is a gotra of Jats found in Rajasthan. They were the protectors of elephants (गज). [1]

History

Ghosundi Inscription of Sarvatata second century BC

|

| Ghosundi Inscription of second century[2] |

The earliest epigraphic evidence regarding the worship of Lord Narayana is found from the Ghosundi Stone Inscription of Maharaja Sarvatata of 1st Century B.C. Ghosundi is a village in the Chittorgarh district of Rajasthan. The inscription record the erection of enclosing wall around the stone object of worship called Narayana Vatika for the divinities Sankarshana and Vasudeva by one Sarvatta who was a devotee of Bhagavat and had performed an Asvamedha Sacrifice. [3]

The Hathibada Ghosundi Inscriptions, sometimes referred simply as the Ghosundi Inscription or the Hathibada Inscription, are among the oldest known Sanskrit inscriptions in the Brahmi script, and dated to the 1st-century BCE. Some scholars, such as Jan Gonda, have dated these to the 2nd century BCE.[4][5]

The Hathibada inscription were found near Nagari village, about 8 miles (13 km) north of Chittorgarh, Rajasthan, India, while the Ghosundi inscription was found in the village of Ghosundi, about 3 miles (4.8 km) southwest of Chittorgarh. They are linked to Vaishnavism tradition of Hinduism.

The Hathibada Ghosundi Inscriptions were found in the same area, but not exactly the same spot. One part was discovered inside an ancient water well in Ghosundi, another at the boundary wall between Ghosundi and Bassi, and the third on a stone slab in the inner wall of Hathibada. The three fragments are each incomplete, but studied together. They are believed to have been displaced because the Mughal emperor Akbar during his seize of Chittorgarh camped at Nagari, built some facilities by breaking and reusing old structures, a legacy that gave the location its name "Hathi-bada" or "elephant stable". The part discovered in the Hathibada wall has the same style, same Brahmi script, and partly same text as the Ghosundi well text, thereby suggesting a link.[6][7]

The inscription is significant not only for its antiquity but as a source of information about ancient Indian scripts, the society, its history and its religious beliefs.[8] It confirms the ancient reverence of Hindu deities Samkarshana-Vasudeva (also known as Balarama-Krishna), an existence of stone temple dedicated to them in 1st-century BCE, the puja tradition, and a king who had completed the Vedic Asvamedha sacrifice.[9][10][11]

Taken together with independent evidence such as the Besnagar inscription found with Heliodorus pillar, the Hathibada Ghosundi Inscriptions suggest that one of the roots of Vaishnavism in the form of Bhagavatism was thriving in ancient India between the 2nd and 1st century BCE.[12][13] They are not the oldest known Hindu inscription, however. Others such as the Ayodhya Inscription and Nanaghat Cave Inscription are generally accepted older or as old.[14][15]

Hathibada Ghosundi Inscriptions

The discovered inscription is incomplete, and has been interpolated based on Sanskrit prosody rules. It reads:[16]

Fragment A

1 ..... tena Gajayanena P(a)rasarlputrena Sa-

2 ..... [j]i[na] bhagavabhyam Samkarshana-V[a]sudevabhya(m)

3 ......bhyam pujasila-prakaro Narayana-vat(i)ka.

Fragment B

1. ....[tr](e)(na) Sarvatatena As[v]amedha....

2 .....sarvesvarabh(yam).

Fragment C

1 ....vat(ena) [Ga]j(a)yan[e]na P(a)r(asaripu)t(re)na [Sa](r)[vata]tena As(vame)[dha](ya)- [j](ina)

2 ....(na)-V(a)sudevabh[y]a(m) anihata(ohyam) sa(r)v(e)[s]va[r](a)bh(yam) p(u)[j](a)- [s](i)l(a)-p[r]a[k]aro Nar[a]yana-vat(i)[k](a). </poem>

– Ghosundi Hathibada Inscriptions, 1st-century BCE[17]

Extrapolation

Bhandarkar proposed that the three fragments suggest what the complete reading of fragment A might have been. His proposal was:

Fragment A (extrapolated)

1 (Karito=yam rajna Bhagava)tena Gajayanena Parasariputrena Sa-

2 (rvatatena Asvamedha-ya)jina bhagava[d*]bhyaih Samkarshana-Vasudevabhyam

3 (anihatabhyarh sarvesvara)bhyam pujasila-prakaro Narayana-vatika.

Translations

Bhandarkar – an archaeologist, translates it as,

(This) enclosing wall round the stone (object) of worship, called Narayana-vatika (Compound) for the divinities Samkarshana-Vasudeva who are unconquered and are lords of all (has been caused to be made) by (the king) Sarvatata, a Gajayana and son of (a lady) of the Parasaragotra, who is a devotee of Bhagavat (Vishnu) and has performed an Asvamedha sacrifice.

– Ghosundi Hathibada Inscriptions, 1st-century BCE[19]

Harry Falk – an Indologist, states that the king does not mention his father by name, only his mother, and in his dedicatory verse does not call himself raja (king).[20] The king belonged to a Hindu Brahmin dynasty of Kanvas, that followed the Hindu Sungas dynasty. He translates one of the fragments as:

adherent of the Lord (bhagavat), belonging to the gotra of the Gajayanas, son of a mother from the Parasara gotra, performer of an Asvamedha.[21]

Benjamín Preciado-Solís – an Indologist, translates it as:

[This] stone enclosure, called the Narayana Vatika, for the worship of Bhagavan Samkarsana and Bhagavan Vasudeva, the invincible lords of all, [was erected] by [the Bhaga]vata king of the line of Gaja, Sarvatata, the victorious, who has performed an asvamedha, son of a Parasari.[22]

घोसुन्डी का लेख द्वितीय शताब्दी ई.पू.

यह लेख कई शिला खण्डों में टूटा हुआ है. इनमें से एक बड़ा खण्ड उदयपुर संग्रहालय में सुरक्षित है. प्रारम्भ में ये लेख घोसुन्डी गांव से, नगरी के निकट, जो चित्तौड़ से सात मील दूर है, प्राप्त हुआ था. लेख की भाषा संस्कत और लिपि ब्राह्मी है. प्रस्तुत लेख में संकर्षण और वासुदेव के पूजाग्रह के चारों ओर पत्थर की चारदिवारी बनाने और गजवंश के सर्वतात द्वारा अश्वमेघ यज्ञ करने का उल्लेख है. ये सर्वतात पाराशरी का पुत्र था यह भी इसमें अंकित है.

श्री जोगेन्द्रनाथ घोष के विचार से इस लेख में वर्णित नाम कण्ववंशीय ब्राह्मण मालूम होता है, जिसमें गाजायन गोत्र का सूचक और सर्वतात व्यक्ति का. जोह्नसन के विचार से यक लेख किसी ग्रीक, शुंग या आन्ध्रवंशीय का होना चाहिय. आन्ध्रों में ’गाजायन’ ’सर्वतात’ आदि नाम उस वंश के शासकों में पाये जाते हैं. जिससे यहां के शासक का आन्ध्रवंशीय होना अनुमानित होता है. इन शिलाखण्डों की पंक्तियां साथ के बाक्स में है.[23]

घोसुंडी

विजयेन्द्र कुमार माथुर[24] ने लेख किया है ... घोसुंडी (AS, p.313) राजस्थान का एक ऐतिहासिक स्थान है। यह स्थान ऐतिहासिक दृष्टि से महत्त्वपूर्ण है। इस स्थान से शुंग कालीन अभिलेख प्राप्त हुए हैं। अभिलेखों से ज्ञात होता है कि द्वितीय शती ई. पू. के लगभग ही देश के इस भाग में भागवत धर्म (वासुदेव कृष्ण की पूजा) का प्रचलन प्रारंभ हो गया था और बौद्ध धर्म अवनति के मार्ग पर बढ़ रहा था। एक अभिलेख में सकर्षण या बलराम की उपासना का भी उल्लेख है।

Notable persons

Population

External links

References

- ↑ Dr Mahendra Singh Arya, Dharmpal Singh Dudee, Kishan Singh Faujdar & Vijendra Singh Narwar: Ādhunik Jat Itihas (The modern history of Jats), Agra 1998 p. 240

- ↑ डॉ गोपीनाथ शर्मा: 'राजस्थान के इतिहास के स्त्रोत', 1983, पृ.43-44

- ↑ God Narayana in the Inscription

- ↑ Jan Gonda (2016). Visnuism and Sivaism: A Comparison. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 166 note 243. ISBN 978-1-4742-8082-2.

- ↑ James Hegarty (2013). Religion, Narrative and Public Imagination in South Asia: Past and Place in the Sanskrit Mahabharata. Routledge. pp. 46 note 118. ISBN 978-1-136-64589-1.

- ↑ D. R. Bhandarkar, Hathi-bada Brahmi Inscription at Nagari, Epigraphia Indica Vol. XXII, Archaeological Survey of India, pages 198-205

- ↑ Dilip K. Chakrabarti (1988). A History of Indian Archaeology from the Beginning to 1947. Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-81-215-0079-1.

- ↑ D. R. Bhandarkar, Hathi-bada Brahmi Inscription at Nagari, Epigraphia Indica Vol. XXII, Archaeological Survey of India, pages 198-205

- ↑ Richard Salomon (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 239–240. ISBN 978-0-19-509984-3.

- ↑ Gerard Colas (2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 230–232. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

- ↑ Rajendra Chandra Hazra (1987). Studies in the Puranic Records on Hindu Rites and Customs. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 200–201. ISBN 978-81-208-0422-7.

- ↑ Gerard Colas (2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 230–232. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

- ↑ Lavanya Vemsani (2016). Krishna in History, Thought, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-1-61069-211-3.

- ↑ Theo Damsteegt (1978). Epigraphical Hybrid Sanskrit. Brill Academic. pp. 209–211.

- ↑ Julia Shaw (2013). Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, C. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD. Routledge. pp. 264 note 14. ISBN 978-1-61132-344-3.

- ↑ D. R. Bhandarkar, Hathi-bada Brahmi Inscription at Nagari, Epigraphia Indica Vol. XXII, Archaeological Survey of India, pages 198-205

- ↑ D. R. Bhandarkar, Hathi-bada Brahmi Inscription at Nagari, Epigraphia Indica Vol. XXII, Archaeological Survey of India, pages 198-205

- ↑ D. R. Bhandarkar, Hathi-bada Brahmi Inscription at Nagari, Epigraphia Indica Vol. XXII, Archaeological Survey of India, pages 198-205

- ↑ D. R. Bhandarkar, Hathi-bada Brahmi Inscription at Nagari, Epigraphia Indica Vol. XXII, Archaeological Survey of India, pages 198-205

- ↑ Harry Falk (2006). Patrick Olivelle (ed.). Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford University Press. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1.

- ↑ Harry Falk (2006). Patrick Olivelle (ed.). Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford University Press. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1.

- ↑ Benjamín Preciado-Solís (1984). The Kṛṣṇa Cycle in the Purāṇas: Themes and Motifs in a Heroic Saga. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-89581-226-1.

- ↑ डॉ गोपीनाथ शर्मा: 'राजस्थान के इतिहास के स्त्रोत', 1983, पृ.43-44

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.313

Back to Jat Villages/Inscriptions