Babylon

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

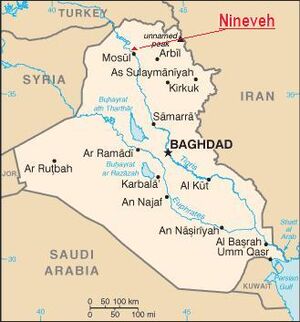

Babylon (बेबीलोन) is a city of ancient Mesopotamia, the remains of which can be found in present-day Al Hillah, Babil Province, Iraq, about 85 kilometers south of Baghdad.

Contents

- 1 Variants of name

- 2 Location

- 3 Origin

- 4 Jat Gotras Namesake

- 5 Jat Gotras Namesake

- 6 Mention by Pliny

- 7 History

- 8 Mention by Pliny

- 9 Mention by Pliny

- 10 Jat History

- 11 Assyrian period

- 12 Neo-Babylonian Empire

- 13 Hellenistic period

- 14 Persian Empire period

- 15 Archaeology of Babylon

- 16 Ch 3.8 Description of Darius-III's Army at Arbela against Alexander

- 17 Ch 3.16: Escape of Darius into Media.— March of Alexander to Babylon and Susa

- 18 Ch 7.22 An Omen of Alexander's Approaching Death

- 19 Further reading

- 20 See also

- 21 References

Variants of name

- Babylonia (Pliny.vi.30, Pliny.vi.39)

- Babel (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 418)

- Babylon (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 94, 153, 171, 172, 224, 239, 808, 372, 385, 396-420.)

- Babylonians (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 155, 156, 161, 171, 402.)

- Babylonia (बेबीलोनिया)

- Babylonian (बेबीलोनिया)

- Al Hillah

- Babil (Province in Iraq)

- Babilu (bāb-ilû, meaning 'Gateway of the god(s)')

- בבל (Babel) (In Bible)

Location

All that remains today of the ancient famed city of Babylon is a mound, or tell, of broken mud-brick buildings and debris in the fertile Mesopotamian plain between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, in Iraq.

Origin

Arrian[1] writes....The Hebrew name for Babylon is Babel, i.e. Bab-Bel, court of Bel: porta vel aula, civitas Beli (Winer). In Jer. xxv. 26; li. 41, it is called Sbeshach, which Jewish commentators, followed by Jerome, explain by the Canon Atbash, i.e. after the alphabet put in an inverted order. According to this rule the word Babel, which is the Hebrew name of Babylon, would be written Sheshach. Sir Henry Rawlinson, however, says it was the name of a god after whom the city was named; and the word has been found among the Assyrian inscriptions representing a deity.

The form Babylon is the Greek variant of Akkadian Babilu (bāb-ilû, meaning "Gateway of the god(s)", translating Sumerian Ka.dingir.ra). In the Bible, the name appears as בבל (Babel), interpreted by Book of Genesis 11:9 to mean "confusion" (of languages), from the verb balbal, "to confuse".

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Babal Jat clan may get name from Babylon, a city of ancient Mesopotamia, the remains of which can be found in present-day Al Hillah, Babil Province, Iraq, about 85 kilometers south of Baghdad.Babylon was also known by names - Babil (a Province in Iraq), Babilu (bāb-ilû, meaning 'Gateway of the god(s)'), Babel (In Bible).

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Babal = Babel (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 418)

- Babal = Babylon (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 94, 153, 171, 172, 224, 239, 808, 372, 385, 396-420.)

- Babal = Babylonians (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 155, 156, 16)

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[2] mentions Mesopotamia .... Babylon, the capital of the nations of Chaldæa, long enjoyed the greatest celebrity of all cities throughout the whole world: and it is from this place that the remaining parts of Mesopotamia and Assyria received the name of Babylonia. The circuit of its walls, which were two hundred feet in height, was sixty miles. These walls were also fifty feet in breadth, reckoning to every foot three fingers' breadth beyond the ordinary measure of our foot. The river Euphrates flowed through the city, with quays of marvellous workmanship erected on either side. The temple there18 of Jupiter Belus19 is still in existence; he was the first inventor of the science of Astronomy. In all other respects it has been reduced to a desert, having been drained of its population in consequence of its vicinity to Seleucia20, founded for that purpose by Nicator, at a distance of ninety miles, on the confluence of the Tigris and the canal that leads from the Euphrates. Seleucia, however, still bears the surname of Babylonia: it is a free and independent city, and retains the features of the Macedonian manners. It is said that the population of this city amounts to six hundred thousand, and that the outline of its walls resembles an eagle with expanded wings: its territory, they say, is the most fertile in all the East.

18 As to the identity of this, see a Note at the beginning of this Chapter.

19 Meaning Jupiter Uranius, or "Heavenly Jupiter," according to Parisot, who observes that Eusebius interprets baal, or bel, "heaven." According to one account, he was the father of king Ninus and son of Nimrod. The Greeks in later times attached to his name many of their legendary fables.

20 The city of Seleucia ad Tigrin, long the capital of Western Asia, until it was eclipsed by Ctesiphon. Its site has been a matter of considerable discussion, but the most probable opinion is, that it stood on the western bank of the Tigris, to the north of its junction with the royal canal (probably the river Chobar above mentioned), opposite to the mouth of the river Delas or Silla (now Diala), and to the spot where Ctesiphon was afterwards built by the Parthians. It stood a little to the south of the modern city of Baghdad; thus commanding the navigation of the Tigris and Euphrates, and the whole plain formed by those two rivers.

History

Historical resources inform us that Babylon was in the beginning a small town that had sprung up by the beginning of the third millennium BC (the dawn of the dynasties). The town flourished and attained prominence and political repute with the rise of the first Babylonian dynasty. It was the "holy city" of Babylonia by approximately 2300 BC, and the seat of the Neo-Babylonian Empire from 612 BC. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The earliest source to mention Babylon may be a dated tablet of the reign of Sargon of Akkad (ca. 24th century BC short chronology). The so-called "Weidner Chronicle" states that it was Sargon himself who built Babylon "in front of Akkad" (ABC 19:51). Another chronicle likewise states that Sargon "dug up the dirt of the pit of Babylon, and made a counterpart of Babylon next to Agade". (ABC 20:18-19).

Some scholars, including linguist Ignace Gelb, have suggested that the name Babil is an echo of an earlier city name. According to Dr. Ranajit Pal, this city was in the East [1]. Herzfeld wrote about Bawer in Iran, which was allegedly founded by Jamshid; the name Babil could be an echo of Bawer. David Rohl holds that the original Babylon is to be identified with Eridu. The Bible in Genesis 10 indicates that Nimrod was the original founder of Babel (Babylon). Joan Oates claims in her book Babylon that the rendering "Gateway of the gods" is no longer accepted by modern scholars.

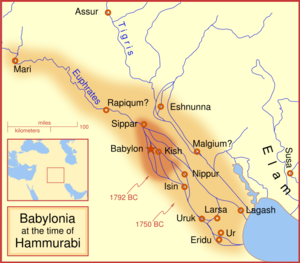

Over the years, the power and population of Babylon waned. From around the 20th century BC, it was occupied by Amorites, nomadic tribes from the west who were Semitic speakers like the Akkadians, but did not practice agriculture like them, preferring to herd sheep. The First Babylonian Dynasty was established by Sumu-abum, but the city-state controlled little surrounding territory until it became the capital of Hammurabi's empire (ca. 18th century BC). Hammurabi is known for codifying the laws of Babylonia into the Code of Hammurabi that was to have a profound influence on the region. From that time onward, the city continued to be the capital of the region known as Babylonia — although during the 440 years of domination by the Kassites (1595–1185 BC), the city was renamed Karanduniash.

The city itself was built upon the Euphrates, and divided in equal parts along its left and right banks, with steep embankments to contain the river's seasonal floods. Babylon grew in extent and grandeur over time, but gradually became subject to the rule of Assyria.

It has been estimated that Babylon was the largest city in the world from ca. 1770 to 1670 BC, and again between ca. 612 and 320 BC. It was perhaps the first city to reach a population above 200,000.[3]

It is recorded that Babylon's legal system developed a form of negligence law, and Babylon was probably the first culture to develop negligence law. In the common law world, the law of negligence was not fully rediscovered until the 20th century.

Assyrian period

During the reign of Sennacherib of Assyria, Babylonia was in a constant state of revolt, led by Mushezib-Marduk, and suppressed only by the complete destruction of the city of Babylon. In 689 BC, its walls, temples and palaces were razed, and the rubble was thrown into the Arakhtu, the sea bordering the earlier Babylon on the south. This act shocked the religious conscience of Mesopotamia; the subsequent murder of Sennacherib was held to be in expiation of it, and his successor Esarhaddon hastened to rebuild the old city, to receive there his crown, and make it his residence during part of the year. On his death, Babylonia was left to be governed by his elder son Shamash-shum-ukin, who eventually headed a revolt in 652 BC against his brother in Nineveh, Assurbanipal.

Once again, Babylon was besieged by the Assyrians and starved into surrender. Assurbanipal purified the city and celebrated a "service of reconciliation", but did not venture to "take the hands" of Bel. In the subsequent overthrow of the Assyrian Empire, the Babylonians saw another example of divine vengeance.

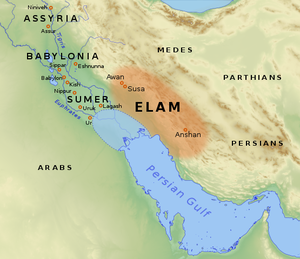

Neo-Babylonian Empire

Under Nabopolassar, Babylon threw off the Assyrian rule in 626 BC, and became the capital of the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

With the recovery of Babylonian independence, a new era of architectural activity ensued, and his son Nebuchadnezzar II (605–562 BC) made Babylon into one of the wonders of the ancient world. Nebuchadnezzar ordered the complete reconstruction of the imperial grounds, including rebuilding the Etemenanki ziggurat and the construction of the Ishtar Gate — the most spectacular of eight gates that ringed the perimeter of Babylon. The Ishtar Gate survives today in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Nebuchadnezzar is also credited with the construction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon (one of the seven wonders of the ancient world), said to have been built for his homesick wife Amyitis. Whether the gardens did exist is a matter of dispute. Although excavations by German archaeologist Robert Koldewey are thought to reveal its foundations, many historians disagree about the location, and some believe it may have been confused with gardens in Nineveh.

Persia captures Babylon

In 539 BC, the Neo-Babylonian Empire fell to Cyrus the Great, king of Persia, with an unprecedented military manoeuvre. The famed walls of Babylon were indeed impenetrable, with the only way into the city through one of its many gates or through the Euphrates, which ebbed beneath its thick walls. Metal gates at the river's in-flow and out-flow prevented underwater intruders, if one could hold one's breath to reach them. Cyrus (or his generals) devised a plan to use the Euphrates as the mode of entry to the city, ordering large camps of troops at each point and instructed them to wait for the signal. Awaiting an evening of a national feast among Babylonians, Cyrus' troops diverted the Euphrates river upstream, causing the Euphrates to drop to wading levels or to dry up altogether. The soldiers marched under the walls through thigh-level water or as dry as mud. The Persian Army conquered the outlying areas of the city's interior while a majority of Babylonians at the city center were oblivious to the breach. The account was elaborated upon by Herodotus,[4] and is also mentioned by passages in the Old Testament.[5][6] Cyrus claimed the city by walking through the gates of Babylon with little or no resistance from the drunken Babylonians.

Cyrus later issued a decree permitting the exiled Jews to return to their own land (as explained in the Old Testament), to allow their temple to be rebuilt back in Jerusalem.

Under Cyrus and the subsequent Persian king Darius the Great, Babylon became the capital city of the 9th Satrapy (Babylonia in the south and Athura in the north), as well as a centre of learning and scientific advancement. In Achaemenid Persia, the ancient Babylonian arts of astronomy and mathematics were revitalised and flourished, and Babylonian scholars completed maps of constellations. The city was the administrative capital of the Persian Empire, the preeminent power of the then known world, and it played a vital part in the history of that region for over two centuries. Many important archaeological discoveries have been made that can provide a better understanding of that era.[7][8]

The early Persian kings had attempted to maintain the religious ceremonies of Marduk, but by the reign of Darius III, over-taxation and the strains of numerous wars led to a deterioration of Babylon's main shrines and canals, and the disintegration of the surrounding region. Despite three attempts at rebellion in 522 BC, 521 BC and 482 BC, the land and city of Babylon remained solidly under Persian rule for two centuries, until Alexander the Great's entry in 331 BC.

Hellenistic period

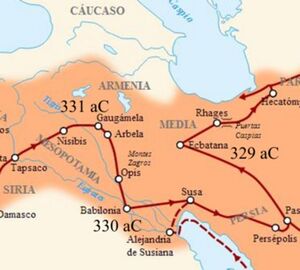

In 331 BC, Darius III was defeated by the forces of the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great at the Battle of Gaugamela, and in October, Babylon fell to the young conqueror. A native account of this invasion notes a ruling by Alexander not to enter the homes of its inhabitants.Template:Fact

Under Alexander, Babylon again flourished as a centre of learning and commerce. But following Alexander's death in 323 BC in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar, his empire was divided amongst his generals, and decades of fighting soon began, with Babylon once again caught in the middle.

The constant turmoil virtually emptied the city of Babylon. A tablet dated 275 BC states that the inhabitants of Babylon were transported to Seleucia, where a palace was built, as well as a temple given the ancient name of Esagila. With this deportation, the history of Babylon comes practically to an end, though more than a century later, it was found that sacrifices were still performed in its old sanctuary. By 141 BC, when the Parthian Empire took over the region, Babylon was in complete desolation and obscurity.

Persian Empire period

Under the Parthian, and later, Sassanid Persians, Babylon remained a province of the Persian Empire for nine centuries, until about 650 AD. It continued to have its own culture and peoples, who spoke varieties of Aramaic, and who continued to refer to their homeland as Babylon. Some examples of their cultural products are often found in the Babylonian Talmud, the Mandaean religion, and the religion of the prophet Mani.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[9] mentions Mesopotamia....The whole of Mesopotamia formerly belonged to the Assyrians, being covered with nothing but villages, with the exception of Babylonia1 and Ninus.2 The Macedonians formed these communities into cities, being prompted thereto by the extraordinary fertility of the soil.

1 The great seat of empire of the Babylonio-Chaldæan kingdom. It either occupied the site, it is supposed, or stood in the immediate vicinity of the tower of Babel. In the reign of Labynedus, Nabonnetus, or Bel- shazzar, it was taken by Cyrus. In the reign of Augustus, a small part only of Babylon was still inhabited, the remainder of the space within the walls being under cultivation. The ruins of Babylon are found to commence a little south of the village of Mohawill, eight miles north of Hillah.

2 Nineveh. See c. 16 of the present Book.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[10] mentions Mesopotamia....Babylon, the capital of the nations of Chaldæa, long enjoyed the greatest celebrity of all cities throughout the whole world: and it is from this place that the remaining parts of Mesopotamia and Assyria received the name of Babylonia. The circuit of its walls, which were two hundred feet in height, was sixty miles. These walls were also fifty feet in breadth, reckoning to every foot three fingers' breadth beyond the ordinary measure of our foot. The river Euphrates flowed through the city, with quays of marvellous workmanship erected on either side. The temple there18 of Jupiter Belus19 is still in existence; he was the first inventor of the science of Astronomy. In all other respects it has been reduced to a desert, having been drained of its population in consequence of its vicinity to Seleucia20, founded for that purpose by Nicator, at a distance of ninety miles, on the confluence of the Tigris and the canal that leads from the Euphrates. Seleucia, however, still bears the surname of Babylonia: it is a free and independent city, and retains the features of the Macedonian manners. It is said that the population of this city amounts to six hundred thousand, and that the outline of its walls resembles an eagle with expanded wings: its territory, they say, is the most fertile in all the East.

18 As to the identity of this, see a Note at the beginning of this Chapter.

19 Meaning Jupiter Uranius, or "Heavenly Jupiter," according to Parisot, who observes that Eusebius interprets baal, or bel, "heaven." According to one account, he was the father of king Ninus and son of Nimrod. The Greeks in later times attached to his name many of their legendary fables.

20 The city of Seleucia ad Tigrin, long the capital of Western Asia, until it was eclipsed by Ctesiphon. Its site has been a matter of considerable discussion, but the most probable opinion is, that it stood on the western bank of the Tigris, to the north of its junction with the royal canal (probably the river Chobar above mentioned), opposite to the mouth of the river Delas or Silla (now Diala), and to the spot where Ctesiphon was afterwards built by the Parthians. It stood a little to the south of the modern city of Baghdad; thus commanding the navigation of the Tigris and Euphrates, and the whole plain formed by those two rivers.

Jat History

Ram Swarup Joon[11] writes that Pliny has written that during a conflict between KhanKesh, a province in Turkey, and Babylonia, they sent for the Sindhu Jats from Sindh. These soldiers wore cotton uniforms and were experts in naval warfare. On return from Turkey they settled down in Syria. They belonged to Hasti dynasty. Asiagh Jats ruled Alexandria in Egypt. Their title was Asii

Arrian[12] writes....Belus, or Bel, the supreme deity of the Babylonians, was identical with the Syrian Baal. The signification of the name is mighty. [13]

Assyrian period

During the reign of Sennacherib of Assyria, Babylonia was in a constant state of revolt, led by Mushezib-Marduk, and suppressed only by the complete destruction of the city of Babylon. In 689 BC, its walls, temples and palaces were razed, and the rubble was thrown into the Arakhtu, the sea bordering the earlier Babylon on the south. This act shocked the religious conscience of Mesopotamia; the subsequent murder of Sennacherib was held to be in expiation of it, and his successor Esarhaddon hastened to rebuild the old city, to receive there his crown, and make it his residence during part of the year. On his death, Babylonia was left to be governed by his elder son Shamash-shum-ukin, who eventually headed a revolt in 652 BC against his brother in Nineveh, Assurbanipal.

Once again, Babylon was besieged by the Assyrians and starved into surrender. Assurbanipal purified the city and celebrated a "service of reconciliation", but did not venture to "take the hands" of Bel. In the subsequent overthrow of the Assyrian Empire, the Babylonians saw another example of divine vengeance.

Neo-Babylonian Empire

Under Nabopolassar, Babylon threw off the Assyrian rule in 626 BC, and became the capital of the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

With the recovery of Babylonian independence, a new era of architectural activity ensued, and his son Nebuchadnezzar II (605–562 BC) made Babylon into one of the wonders of the ancient world. Nebuchadnezzar ordered the complete reconstruction of the imperial grounds, including rebuilding the Etemenanki ziggurat and the construction of the Ishtar Gate — the most spectacular of eight gates that ringed the perimeter of Babylon. The Ishtar Gate survives today in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Nebuchadnezzar is also credited with the construction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon (one of the seven wonders of the ancient world), said to have been built for his homesick wife Amyitis. Whether the gardens did exist is a matter of dispute. Although excavations by German archaeologist Robert Koldewey are thought to reveal its foundations, many historians disagree about the location, and some believe it may have been confused with gardens in Nineveh.

Persia captures Babylon

In 539 BC, the Neo-Babylonian Empire fell to Cyrus the Great, king of Persia, with an unprecedented military manoeuvre. The famed walls of Babylon were indeed impenetrable, with the only way into the city through one of its many gates or through the Euphrates, which ebbed beneath its thick walls. Metal gates at the river's in-flow and out-flow prevented underwater intruders, if one could hold one's breath to reach them. Cyrus (or his generals) devised a plan to use the Euphrates as the mode of entry to the city, ordering large camps of troops at each point and instructed them to wait for the signal. Awaiting an evening of a national feast among Babylonians, Cyrus' troops diverted the Euphrates river upstream, causing the Euphrates to drop to wading levels or to dry up altogether. The soldiers marched under the walls through thigh-level water or as dry as mud. The Persian Army conquered the outlying areas of the city's interior while a majority of Babylonians at the city center were oblivious to the breach. The account was elaborated upon by Herodotus,[14] and is also mentioned by passages in the Old Testament.[15][16] Cyrus claimed the city by walking through the gates of Babylon with little or no resistance from the drunken Babylonians.

Cyrus later issued a decree permitting the exiled Jews to return to their own land (as explained in the Old Testament), to allow their temple to be rebuilt back in Jerusalem.

Under Cyrus and the subsequent Persian king Darius the Great, Babylon became the capital city of the 9th Satrapy (Babylonia in the south and Athura in the north), as well as a centre of learning and scientific advancement. In Achaemenid Persia, the ancient Babylonian arts of astronomy and mathematics were revitalised and flourished, and Babylonian scholars completed maps of constellations. The city was the administrative capital of the Persian Empire, the preeminent power of the then known world, and it played a vital part in the history of that region for over two centuries. Many important archaeological discoveries have been made that can provide a better understanding of that era.[17][18]

The early Persian kings had attempted to maintain the religious ceremonies of Marduk, but by the reign of Darius III, over-taxation and the strains of numerous wars led to a deterioration of Babylon's main shrines and canals, and the disintegration of the surrounding region. Despite three attempts at rebellion in 522 BC, 521 BC and 482 BC, the land and city of Babylon remained solidly under Persian rule for two centuries, until Alexander the Great's entry in 331 BC.

Hellenistic period

Please improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unverifiable material may be challenged and removed.

In 331 BC, Darius III was defeated by the forces of the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great at the Battle of Gaugamela, and in October, Babylon fell to the young conqueror. A native account of this invasion notes a ruling by Alexander not to enter the homes of its inhabitants.[citation needed]

Under Alexander, Babylon again flourished as a centre of learning and commerce. But following Alexander's death in 323 BC in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar, his empire was divided amongst his generals, and decades of fighting soon began, with Babylon once again caught in the middle.

The constant turmoil virtually emptied the city of Babylon. A tablet dated 275 BC states that the inhabitants of Babylon were transported to Seleucia, where a palace was built, as well as a temple given the ancient name of Esagila. With this deportation, the history of Babylon comes practically to an end,[citation needed] though more than a century later, it was found that sacrifices were still performed in its old sanctuary. By 141 BC, when the Parthian Empire took over the region, Babylon was in complete desolation and obscurity.

Persian Empire period

Under the Parthian, and later, Sassanid Persians, Babylon remained a province of the Persian Empire for nine centuries, until about 650 AD. It continued to have its own culture and peoples, who spoke varieties of Aramaic, and who continued to refer to their homeland as Babylon. Some examples of their cultural products are often found in the Babylonian Talmud, the Mandaean religion, and the religion of the prophet Mani.

Archaeology of Babylon

Historical knowledge of Babylon's topography is derived from classical writers, the inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar, and several excavations, including those of the Deutsche Orientgesellschaft begun in 1899. The layout is that of the Babylon of Nebuchadnezzar; the older Babylon destroyed by Sennacherib having left few, if any, traces behind.

Most of the existing remains lie on the east bank of the Euphrates, the principal ones being three vast mounds: the Babil to the north, the Qasr or "Palace" (also known as the Mujelliba) in the centre, and the Ishgn "Amran ibn" All, with the outlying spur of the Jumjuma, to the south. East of these come the Ishgn el-Aswad or "Black Mound" and three lines of rampart, one of which encloses the Babil mound on the north and east sides, while a third forms a triangle with the southeast angle of the other two. West of the Euphrates are other ramparts, and the remains of the ancient Borsippa.

We learn from Herodotus and Ctesias that the city was built on both sides of the river in the form of a square, and was enclosed within a double row of lofty walls, or a triple row according to Ctesias. Ctesias describes the outermost wall as 360 stades (68 kilometers/42 mi) in circumference, while according to Herodotus it measured 480 stades (90 kilometers/56 mi), which would include an area of about 520 square kilometers (200 sq mi).

The estimate of Ctesias is essentially the same as that of Q. Curtius (v. I. 26) — 368 stades — and Cleitarchus (ap. Diod. Sic. ii. 7) — 365 stades; Strabo (xvi. 1. 5) makes it 385 stades. But even the estimate of Ctesias, assuming the stade to be its usual length, would imply an area of about 260 square kilometers (100 sq mi). According to Herodotus, the width of the walls was 24 m.

Ch 3.8 Description of Darius-III's Army at Arbela against Alexander

They come to the aid of Darius-III (the last king of the Achaemenid Empire of Persia) and were part of alliance in the battle of Gaugamela (331 BC) formed by Darius-III in war against Alexander the Great at Arbela, now known as Arbil, which is the capital of Kurdistan Region in northern Iraq.

Arrian[19] writes....Alexander therefore took the royal squadron of cavalry, and one squadron of the Companions, together with the Paeonian scouts, and marched with all speed; having ordered the rest of his army to follow at leisure. The Persian cavalry, seeing Alexander, advancing quickly, began to flee with all their might. Though he pressed close upon them in pursuit, most of them escaped; but a few, whose horses were fatigued by the flight, were slain, others were taken prisoners, horses and all. From these they ascertained that Darius with a large force was not far off. For the Indians who were conterminous with the Bactrians, as also the Bactrians themselves and the Sogdianians had come to the aid of Darius, all being under the command of Bessus, the viceroy of the land of Bactria. They were accompanied by the Sacians, a Scythian tribe belonging to the Scythians who dwell in Asia.[1] These were not subject to Bessus, but were in alliance with Darius. They were commanded by Mavaces, and were horse-bowmen. Barsaentes, the viceroy of Arachotia, led the Arachotians[2] and the men who were called mountaineer Indians. Satibarzanes, the viceroy of Areia, led the Areians,[3] as did Phrataphernes the Parthians, Hyrcanians, and Tapurians,[4] all of whom were horsemen. Atropates commanded the Medes, with whom were arrayed the Cadusians, Albanians, and Sacesinians.[5] The men who dwelt near the Red Sea[6] were marshalled by Ocondobates, Ariobarzanes, and Otanes. The Uxians and Susianians[7] acknowledged Oxathres son of Aboulites as their leader, and the Babylonians were commanded by Boupares. The Carians who had been deported into central Asia, and the Sitacenians[8] had been placed in the same ranks as the Babylonians. The Armenians were commanded by Orontes and Mithraustes, and the Cappadocians by Ariaoes. The Syrians from the vale between Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon (i.e. Coele-Syria) and the men of Syria which lies between the rivers[9] were led by Mazaeus. The whole army of Darius was said to contain 40,000 cavalry, 1,000,000 infantry, and 200 scythe-bearing chariots.[10] There were only a few elephants, about fifteen in number, belonging to the Indians who live this side of the Indus.[11] With these forces Darius had encamped at Gaugamela, near the river Bumodus, about 600 stades distant from the city of Arbela, in a district everywhere level;[12] for whatever ground thereabouts was unlevel and unfit for the evolutions of cavalry, had long before been levelled by the Persians, and made fit for the easy rolling of chariots and for the galloping of horses. For there were some who persuaded Darius that he had forsooth got the worst of it in the battle fought at Issus, from the narrowness of the battle-field; and this he was easily induced to believe.

1. Cf. Aelian (Varia Historia, xii. 38).

2. Arachosia comprised what is now the south-east part of Afghanistan and the north-east part of Beloochistan.

3. Aria comprised the west and north-west part of Afghanistan and the east part of Khorasan.

4. Parthia is the modern Khorasan. Hyrcania was the country south and south-east of the Caspian Sea. The Tapurians dwelt in the north of Media, on the borders of Parthia between the Caspian passes. Cf. Ammianus, xxiii. 6.

5. The Cadusians lived south-west of the Caspian, the Albanians on the west of the same sea, in the south-east part of Georgia, and the Sacesinians in the north-east of Armenia, on the river Kur.

6. "The Red Sea was the name originally given to the whole expanse of sea to the west of India as far as Africa. The name was subsequently given to the Arabian Gulf exclusively. In Hebrew it is called Yam-Suph (Sea of Sedge, or a seaweed resembling wool). The Egyptians called it the Sea of Weeds.

7. The Uxians occupied the north-west of Persis, and Susiana was the country to the north and west of Persis.

8. The Sitacenians lived in the south of Assyria. ἐτετάχατο. is the Ionic form for τεταγμἑνοι ἦσαν.

9. The Greeks called this country Mesopotamia because it lies between the rivers Euphrates and Tigris. In the Bible it is called Paddan-Aram (the plain of Aram, which is the Hebrew name of Syria). In Gen. xlviii. 7 it is called merely Paddan, the plain. In Hos. xii. 12, it is called the field of Aram, or, as our Bible has it, the country of Syria. Elsewhere in the Bible it is called Aram-naharaim, Aram of the two rivers, which the Greeks translated Mesopotamia. It is called "the Island," by Arabian geographers.

10. Curtius (iv. 35 and 45) states that Darius had 200,000 infantry, 45,000 cavalry, and 200 scythed chariots; Diodorus (xvii. 53) says, 800,000 infantry, 200,000 cavalry, and 200 scythed chariots; Justin (xi. 12) gives 400,000 foot and 100,000 horse; and Plutarch (Alex., 31) speaks of a million of men. For the chariots cf. Xenophon (Anab., i 8, 10); Livy, xxxvii. 41.

11. This is the first instance on record of the employment of elephants in battle.

12. This river is now called Ghasir, a tributary of the Great Zab. The village Gaugamela was in the district of Assyria called Aturia, about 69 miles from the city of Arbela, now called Erbil.

Ch 3.16: Escape of Darius into Media.— March of Alexander to Babylon and Susa

Arrian[20] writes.... Immediately after the battle, Darius marched through the mountains of Armenia towards Media, accompanied in his flight by the Bactrian cavalry, as they had then been posted with him in the battle; also by those Persians who were called the king's kinsmen, and by a few of the men called apple-bearers.[1] About 2,000 of his Grecian mercenaries also accompanied him in his flight, under the command of Paron the Phocian, and Glaucus the Aetolian. He fled towards Media for this reason, because he thought Alexander would take the road to Susa and Babylon immediately after the battle, inasmuch as the whole of that country was inhabited and the road was not difficult for the transit of baggage; and besides Babylon and Susa appeared to be the prizes of the war; whereas the road towards Media was by no means easy for the march of a large army. In this conjecture Darius was mistaken; for when Alexander started from Arbela, he advanced straight towards Babylon; and when he was now not far from that city, he drew up his army in order of battle and marched forward. The Babylonians came out to meet him in mass, with their priests and rulers, each of whom individually brought gifts, and offered to surrender their city, citadel, and money.[2] Entering the city, he commanded the Babylonians to rebuild all the temples which Xerxes had destroyed, and especially that of Belus, whom the Babylonians venerate more than any other god.[3] He then appointed Mazaeus viceroy of the Babylonians, Apollodorus the Amphipolitan general of the soldiers who were left behind with Mazaeus, and Asclepiodorus, son of Philo, collector of the revenue. He also sent Mithrines, who had surrendered to him the citadel of Sardis, down into Armenia to be viceroy there.[4] Here also he met with the Chaldaeans; and whatever they directed in regard to the religious rites of Babylon he performed, and in particular he offered sacrifice to Belus according to their instructions.[5] He then marched away to Susa[6]; and on the way he was met by the son of the viceroy of the Susians,[7] and a man bearing a letter from Philoxenus, whom he had despatched to Susa directly after the battle. In the letter Philoxenus had written that the Susians had surrendered their city to him, and that all the money was safe for Alexander. In twenty days the king arrived at Susa from Babylon; and entering the city he took possession of the money, which amounted to 50,000 talents, as well as the rest of the royal property.[8] Many other things were also captured there, which Xerxes brought with him from Greece, especially the brazen statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton.[9] These Alexander sent back to the Athenians, and they are now standing at Athens in the Ceramicus, where we go up into the Acropolis,[10] right opposite the temple of Rhea, the mother of the gods, not far from the altar of the Eudanemi. Whoever has been initiated in the mysteries of the two goddesses[11] at Eleusis, knows the altar of Eudanemus which is upon the plain. At Susa Alexander offered sacrifice after the custom of his fathers, and celebrated a torch race and a gymnastic contest; and then, leaving Abulites, a Persian, as viceroy of Susiana, Mazarus, one of his Companions, as commander of the garrison in the citadel of Susa, and Archelaüs, son of Theodorus, as general, he advanced towards the land of the Persians. He also sent Menes down to the sea, as governor of Syria, Phœnicia, and Cilicia, giving him 3,000 talents of silver[12] to convey to the sea, with orders to despatch as many of them to Antipater as he might need to carry on the war against the Lacedaemonians.[13] There also Amyntas, son of Andromenes, reached him with the forces which he was leading from Macedonia[14]; of whom Alexander placed the horsemen in the ranks of the Companion cavalry, and the foot he added to the various regiments of infantry, arranging each according to nationalities. He also established two companies in each squadron of cavalry, whereas before this time companies did not exist in the cavalry; and over them he set as captains those of the Companions who were pre-eminent for merit.

1. As to the kinsmen and apple-bearers, see iii. 11 supra.

2. Diodorus (xvii. 63) and Curtius (v. 6) state that from the treasure captured in Babylon, Alexander distributed to each Macedonian horseman about £24, to each of the Grecian horsemen £20, to each of the Macedonian infantry £8, and to the allied infantry two months' pay.

3. Belus, or Bel, the supreme deity of the Babylonians, was identical with the Syrian Baal. The signification of the name is mighty. Cf. Herodotus (i. 181); Diodorus (ii. 9); Strabo (xvi. 1).

4. See i. 17 supra.

5. The Chaldees appear in Hebrew under the name of Casdim, who seem to have originally dwelt in Carduchia, the northern part of Assyria. The Assyrians transported these rude mountaineers to the plains of Babylonia (Isa. xxiii. 13). The name of Casdim, or Chaldees, was applied to the inhabitants of Mesopotamia (Gen. xi. 28); the inhabitants of the Arabian desert in the vicinity of Edom (Job i. 17); those who dwelt near the river Chaboras (Ezek. i. 3; xi. 24); and the priestly caste who had settled at a very early period in Babylon, as we are informed by Diodorus and Eusebius. Herodotus says that these priests were dedicated to Belus. It is proved by inscriptions that the ancient language was retained as a learned and religious literature. This is probably what is meant in Daniel i. 4 by "the book and tongue of the Casdim." Cf. Diodorus (ii. 29-31); Ptolemy (v. 20, 3); and Cicero (De Divinatione, i. 1). See Fürst's Hebrew Lexicon, sub voce כֶּֽשֶֹד.

6. In the Bible this city is called Shushan. Near it was the fortress of Shushan, called in our Bible the Palace (Neb. i. 2; Esth. ii. 8). Susa was situated on the Choaspes, a river remarkable for the excellence of its water, a fact referred to by Tibullus (iv. 1, 140) and by Milton (Paradise Reg., iii. 288). The name Shushan is derived from the Persian word for lily, which grew abundantly in the vicinity. The ruins of the palace mentioned in Esther i. have recently been explored, and were found to consist of an immense hall, the roof of which was supported by a central group of thirty-six pillars arranged in the form of a square. This was flanked by three porticoes, each containing two rows of six pillars. Cf. Strabo (xv. 7, 28).

7. The name of the viceroy was Abulites (Curtius, v. 8).

8. If these were Attic talents, the amount would be, equivalent to £11,600,000; but if they were Babylonian or Aeginetan talents, they were equal to £19,000,000. Cf. Plutarch (Alex., 36, 37); Justin (xi. 14); and Curtius (v. 8). Diodorus (xvii. 66) tells us that 40,000 talents were of uncoined gold and silver, and 9,000 talents of gold bearing the effigy of Darius.

9. Cf. Arrian (vii. 19); Pausanias (i. 8, 5); Pliny (Nat. Hist., xxxiv. 9); Valerius Maximus (ii. 10, 1). For Harmodius and Aristogeiton see Thucydides, vi. 56-58.

10. Polis meant in early times a particular part of Athens, viz. the citadel, usually called the Acropolis. Cf. Aristophanes (Lysistrata, 245 et passim).

11. Demeter and Persephone.

12.About £730,000.

13. Antipater had been left by Alexander regent of Macedonia. Agis III., king of Sparta, refused to acknowledge Alexander's hegemony, and after a hard struggle was defeated and slain by Antipater at Megalopolis, B.C. 330. See Diodorus, xvii. 63; Curtius, vi. 1 and 2.

14. According to Curtius (v. 6) these forces amounted to nearly 15,000 men. Amyntas also brought with him fifty sons of the chief laen in Macedonia, who wished to serve as royal pages. Cf. Diodorus, xvii. 64.

Ch 7.22 An Omen of Alexander's Approaching Death

Arrian[21] writes.... Having thus proved the falsity of the prophecy of the Chaldaeans, by not having experienced any unpleasant fortune in Babylon,[1] as they had predicted, but having marched out of that city without suffering any mishap, he grew confident in spirit and sailed again through the marshes, having Babylon on his left hand. Here a part of his fleet lost its way in the narrow branches of the river through want of a pilot, until he sent a man to pilot it and lead it back into the channel of the river. The following story is told. Most of the tombs of the Assyrian kings had been built among the pools and marshes.[2] When Alexander was sailing through these marshes, and, as the story goes, was himself steering the trireme, a strong gust of wind fell upon his broadbrimmed Macedonian hat, and the fillet which encircled it. The hat, being heavy, fell into the water; but the fillet, being carried along by the wind, was caught by one of the reeds growing near the tomb of one of the ancient kings.[3] This incident itself was an omen of what was about to occur, and so was the fact that one of the sailors[4] swam off towards the fillet and snatched it from the reed. But he did not carry it in his hands, because it would have been wetted while he was swimming; he therefore put it round his own head and thus conveyed it to the king. Most of the biographers of Alexander say that the king presented him with a talent as a reward for his zeal, and then, ordered his head to be cut off; as the prophets had directed him not to permit that head to be safe which had worn the royal fillet. However, Aristobulus says that the man received a talent; but afterwards also received a scourging for placing the fillet round his head. The same author says that it was one of the Phoenician sailors who fetched the fillet for Alexander; but there are some who say it was Seleucus, and that this was an omen to Alexander of his death and to Seleucus of his great kingdom. For that of all those who succeeded to the sovereignty after Alexander, Seleucus became the greatest king, was the most kingly in mind, and ruled over the greatest extent of land after Alexander himself, does not seem to me to admit of question.[5]

1. The Hebrew name for Babylon is Babel, i.e. Bab-Bel, court of Bel: porta vel aula, civitas Beli (Winer). In Jer. xxv. 26; li. 41, it is called Sbeshach, which Jewish commentators, followed by Jerome, explain by the Canon Atbash, i.e. after the alphabet put in an inverted order. According to this rule the word Babel, which is the Hebrew name of Babylon, would be written Sheshach. Sir Henry Rawlinson, however, says it was the name of a god after whom the city was named; and the word has been found among the Assyrian inscriptions representing a deity.

2. The perfect passive δεδόμημαι is equivalent to the Epic and Ionic form δέδμημαι.

3. σχεθῆναι. See p. 268, note 4.

4. τῶν τὶς ναυτῶν. This position of τίς is an imitation of the usage in Ionic prose. Cf. Herod, i. 85; τῶν τὶς. See Liddell and Scott, sub voce τίς. Cf. Arrian, ii. 26, 4; vi. 9, 3; vii. 3, 4; 22, 5; 24, 2.

5. Cf. Arrian v. 13 supra.

Further reading

- Joan Oates, Babylon, [Ancient Peoples and Places], Thames and Hudson, 1986. ISBN 0-500-02095-7 (hardback) ISBN 0-500-27384-7 (paperback)

See also

- List of Kings of Babylon

- Mesopotamia

- Assyria

- Akkad, Assur

- Tower of Babel, Babel

- Tomb of Daniel

- Province of Babil

References

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/7b, Ch.22, f.n.

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 30

- ↑ Rosenberg, Matt T. Largest Cities Through History, About.com. Accessed April 19, 2008.

- ↑ Herodotus, Book 1, Section 191

- ↑ Isaiah 44:27

- ↑ Jeremiah 50-51

- ↑ Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia The British Museum. Accessed April 19, 2008.

- ↑ Mesopotamia: The Persians

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 30

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 30

- ↑ Ram Sarup Joon: History of the Jats/Chapter III, p.40-41

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/3b, Ch.16, f.n.3

- ↑ Cf. Herodotus (i. 181); Diodorus (ii. 9); Strabo (xvi. 1).

- ↑ Herodotus, Book 1, Section 191

- ↑ Isaiah 44:27

- ↑ Jeremiah 50-51

- ↑ Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia The British Museum. Accessed April 19, 2008.

- ↑ Mesopotamia: The Persians

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/3a, Ch.8

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/3b, Ch.16

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/7b, Ch.22