Northeast Africa

Northeast Africa (उत्तरपूर्व अफ्रीका) or the Horn of Africa is a peninsula in Africa.[1] In ancient and medieval times, the Horn of Africa was referred to as the Bilad al Barbar ("Land of the Barbarians").[2]

Contents

Location

It extends hundreds of kms into the Arabian Sea and lies along the southern side of the Gulf of Aden. The area is the easternmost projection of the African continent. Referred to in ancient and medieval times as the land of the Barbara and Habesha,[3] the Horn of Africa denotes the region containing the countries of Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia.[4]

Variants

This peninsula is known by various names.

- Bilad al Barbar = "Land of the Barbarians". In ancient and medieval times, the Horn of Africa was referred to as the Bilad al Barbar ("Land of the Barbarians").[5]

- Somali Peninsula: It is also known as the Somali Peninsula, or in the Somali language, Geeska Afrika, Jasiiradda Soomaali or Gacandhulka Soomaali.[6]

- HoA: The Horn of Africa is sometimes shortened to HoA or is quite commonly designated simply the "Horn", while inhabitants are sometimes colloquially referred to as Horn Africans.[7]

- Greater Horn of Africa: Sometimes the term Greater Horn of Africa is used, either to be inclusive of neighbouring northeast African countries, or to distinguish the broader geopolitical definition of the Horn of Africa from narrower peninsular definitions.[8]

- Ancient Greeks and Romans referred to the Somali peninsula as Regio Aromatica or Regio Cinnamonifora due to the aromatic plants, or Regio Incognita owing to its uncharted territory.

- Abyssinian Peninsula: Certain media outlets and scholars might define the region as Abyssinian Peninsula.[9]

- In other languages that are local or adjacent to the Horn of Africa, it is known as የአፍሪካ ቀንድ yäafrika qänd in Amharic, القرن الأفريقي al-qarn al-'afrīqī in Arabic, Gaaffaa Afriikaa in Oromo and ቀርኒ ኣፍሪቃ in Tigrinya.

History

According to both genetic and fossil evidence archaic humans evolved into anatomically modern humans in the Horn of Africa around 200,000 years ago and dispersed from the Horn of Africa.[10]][11][12][13][14]

Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) from southern Ethiopia is the oldest anatomically modern Homo sapiens skeleton currently known (196 ± 5 ka).[15] The recognition of Homo sapiens idaltu and Omo Kibish I as anatomically modern humans would justify the description of contemporary humans with the subspecies name Homo sapiens sapiens. A comprehensive review concluded that the more complete fossils represent some of the most significant discoveries of early Homo sapiens made thus far, owing not only to the morphological information they possess, but also to their well constrained geochronology and archaeological context.[16][17][18] Because of their early dating and unique physical characteristics idaltu and kibish represent the immediate ancestors of anatomically modern humans as suggested by Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosomal Adam[19][20][21] and the Out-of-Africa theory.[22][23][24]

Migration

The Southern migration route of the Out of Africa occurred in the Horn of Africa through the Bab el Mandeb. Today at the Bab-el-Mandeb straits, the Red Sea is about 12 miles (20 kms) wide, but 50,000 years ago it was much narrower and sea levels were 70 meters lower. Though the straits were never completely closed, there may have been islands in between which could be reached using simple rafts. Shell middens 125,000 years old have been found in Eritrea,[32] indicating the diet of early humans included seafood obtained by beachcombing.

The findings of the Earliest Stone-Tipped Projectiles from the Ethiopian Rift dated to more than 279,000 years ago in combination with the existing archaeological, fossil and genetic evidence, isolate this region as a source of modern cultures and biology, and it is considered the place of origin of humankind.[25][26]

According to linguists, the Horn of Africa is the proposed original homeland of the Proto-Afroasiatic language as it is considered the region the Afroasiatic languages family displays the greatest diversity, a sign often viewed to represent a geographic origin.[35] The Horn of Africa is also the place where the haplogroup E1b1b originated. Christopher Ehret and Shomarka Keita have suggested that the geography of the E1b1b lineage coincides with the distribution of the Afroasiatic languages.[27] Genetic analysis done on the Afroasiatic speaking population further found that a pre-agricultural back-to-Africa migration into the Horn of Africa occurred through Egypt 23,000 years ago and it brought a non-African ancestry dubbed Ethio-Somali in the region.[28]

Ethiopian agriculture established the earliest known use of the seed grass teff (Poa abyssinica) between 4000–1000 BCE.[29] Teff is used to make the flatbread injera/taita. Coffee also originated in Ethiopia and has since spread to become a worldwide beverage.[30]

Ancient history

Together with northern Somalia, Djibouti, the Red Sea coast of Sudan and Eritrea is considered the most likely location of the land known to the ancient Egyptians as Punt (or "Ta Netjeru," meaning god's land), whose first mention dates to the 25th century BCE.[31]

Dʿmt was a kingdom located in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia, which existed during the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. With its capital at Yeha, the kingdom developed irrigation schemes, used plows, grew millet, and made iron tools and weapons. After the fall of Dʿmt in the 5th century BCE, the plateau came to be dominated by smaller successor kingdoms, until the rise of one of these kingdoms during the 1st century, the Aksumite Kingdom, which was able to reunite the area.[32]

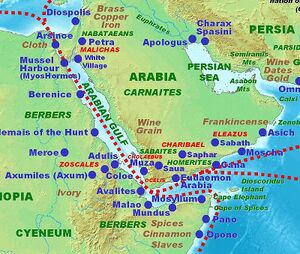

The Kingdom of Aksum (also known as the Aksumite Empire) was an ancient state located in the Eritrean highlands and Ethiopian highlands, which thrived between the 1st and 7th centuries CE. A major player in the commerce between the Roman Empire and Ancient India, Aksum's rulers facilitated trade by minting their own currency. The state also established its hegemony over the declining Kingdom of Kush and regularly entered the politics of the kingdoms on the Arabian peninsula, eventually extending its rule over the region with the conquest of the Himyarite Kingdom. Under Ezana (fl. 320–360), the kingdom of Aksum became the first major empire to adopt Christianity, and was named by Mani as one of the four great powers of his time, along with Persia, Rome and China.

Northern Somalia was an important link in the Horn, connecting the region's commerce with the rest of the ancient world. Somali sailors and merchants were the main suppliers of frankincense, myrrh and spices, all of which were valuable luxuries to the Ancient Egyptians, Phoenicians, Mycenaeans, Babylonians and Romans.[33][34] The Romans consequently began to refer to the region as Regio Aromatica. In the classical era, several flourishing Somali city-states such as Opone, Mosylon and Malao also competed with the Sabaeans, Parthians and Axumites for the rich Indo-Greco-Roman trade.[35]

The birth of Islam

The birth of Islam opposite the Horn's Red Sea coast meant that local merchants and sailors living on the Arabian Peninsula gradually came under the influence of the new religion through their converted Arab Muslim trading partners. With the migration of Muslim families from the Islamic world to the Horn in the early centuries of Islam, and the peaceful conversion of the local population by Muslim scholars in the following centuries, the ancient city-states eventually transformed into Islamic Mogadishu, Berbera, Zeila, Barawa and Merka, which were part of the Barbara civilization.[36][37] The city of Mogadishu came to be known as the "City of Islam"[38] and controlled the East African gold trade for several centuries.[39]

External links

See also

References

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, inc, Jacob E. Safra, The New Encyclopædia Britannica, (Encyclopædia Britannica: 2002), p.61: "The northern mountainous area, known as the Horn of Africa, comprises Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia."

- ↑ George Wynn Brereton Huntingford, Agatharchides, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: With Some Extracts from Agatharkhidēs "On the Erythraean Sea", (Hakluyt Society: 1980), p.83

- ↑ J. D. Fage, Roland Oliver, Roland Anthony Oliver, The Cambridge History of Africa, (Cambridge University Press: 1977), p.190

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, inc, Jacob E. Safra, The New Encyclopædia Britannica, (Encyclopædia Britannica: 2002), p.61: "The northern mountainous area, known as the Horn of Africa, comprises Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia."

- ↑ George Wynn Brereton Huntingford, Agatharchides, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: With Some Extracts from Agatharkhidēs "On the Erythraean Sea", (Hakluyt Society: 1980), p.83

- ↑ Ciise, Jaamac Cumar. Taariikhdii daraawiishta iyo Sayid Maxamad Cabdille Xasan, 1895-1920. JC Ciise, 2005.

- ↑ eklehaimanot, Hailay Kidu. "A Mobile Based Tigrigna Language Learning Tool." International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (iJIM) 9.2 (2015): 50-53.

- ↑ Schmidt, Johannes Dragsbaek; Kimathi, Leah; Owiso, Michael Omondi (13 May 2019). Refugees and Forced Migration in the Horn and Eastern Africa: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities. Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-03721-5.

- ↑ https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/xenophobia-threatens-undermine-sudan-revolution-191228092525666.html

- ↑ Chan, Eva, K. F.; et al. (28 October 2019). "Human origins in a southern African palaeo-wetland and first migrations". Nature. 857 (7781): 185–189. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1714-1. PMID 31659339.

- ↑ Cabrera VM, Marrero P, Abu-Amero KK, Larruga JM (June 2018). "Carriers of mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup L3 basal lineages migrated back to Africa from Asia around 70,000 years ago". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 18 (1): 98. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1211-4. PMC 6009813. PMID 29921229.

- ↑ Holt, Brigitte M. (1 January 2015), Muehlenbein, Michael P. (ed.), "Chapter 13 - Anatomically Modern Homo sapiens", Basics in Human Evolution, Academic Press, pp. 177–192, ISBN 978-0-12-802652-6,

- ↑ Ghirotto S; Penso-Dolfin L; Barbujani G. (August 2011). "Genomic evidence for an African expansion of anatomically modern humans by a Southern route". Human Biology. 83 (4): 477–89. doi:10.3378/027.083.0403. PMID 21846205. "Data on cranial morphology have been interpreted as suggesting that, before the main expansion from Africa through the Near East, anatomically modern humans may also have taken a Southern route from the Horn of Africa through the Arabian peninsula to India, Melanesia and Australia, about 100,000 yrs ago."

- ↑ Mellars, P; KC, Gori; M, Carr; PA, Soares; Richards, MB (June 2013). "Genetic and archaeological perspectives on the initial modern human colonization of southern Asia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (26): 10699–704. doi:10.1073/pnas.1306043110. PMC 3696785. PMID 23754394. "These data support a coastally oriented dispersal of modern humans from eastern Africa to southern Asia ∼60-50 thousand years ago (ka). This was associated with distinctively African microlithic and "backed-segment" technologies analogous to the African "Howiesons Poort" and related technologies, together with a range of distinctively "modern" cultural and symbolic features (highly shaped bone tools, personal ornaments, abstract artistic motifs, microblade technology, etc.), similar to those that accompanied the replacement of "archaic" Neanderthal by anatomically modern human populations in other regions of western Eurasia at a broadly similar date."

- ↑ Hammond, Ashley S.; Royer, Danielle F.; Fleagle, John G. (July 2017). "The Omo-Kibish I pelvis". Journal of Human Evolution. 108: 199–219. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.04.004. ISSN 1095-8606. PMID 28552208.

- ↑ "Human emergence: Perspectives from Herto, Afar Rift, Ethiopia".

- ↑ WoldeGabriel, Giday; Renne, Paul R.; Hart, William K.; Ambrose, Stanley; Asfaw, Berhane; White, Tim D. (2004). "Geoscience methods lead to paleo-anthropological discoveries in Afar Rift, Ethiopia". Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union. 85 (29): 107. doi:10.1029/2004eo290001. ISSN 0096-3941.

- ↑ Beyene, Yonas (29 April 2010), "Herto Brains and Minds: Behaviour of Early Homo sapiens from the Middle Awash", Social Brain, Distributed Mind, British Academy, doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197264522.003.0003, ISBN 9780197264522

- ↑ Francalacci, Paolo; Morelli, Laura; Angius, Andrea; Berutti, Riccardo; Reinier, Frederic; Atzeni, Rossano; Pilu, Rosella; Busonero, Fabio; Maschio, Andrea; Zara, Ilenia; Sanna, Daria (2 August 2013). "Low-Pass DNA Sequencing of 1200 Sardinians Reconstructs European Y-Chromosome Phylogeny". Science (New York, N.Y.). 341 (6145): 565–569. doi:10.1126/science.1237947. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 5500864. PMID 23908240.

- ↑ Poznik, G. David; Henn, Brenna M.; Yee, Muh-Ching; Sliwerska, Elzbieta; Euskirchen, Ghia M.; Lin, Alice A.; Snyder, Michael; Quintana-Murci, Lluis; Kidd, Jeffrey M.; Underhill, Peter A.; Bustamante, Carlos D. (2 August 2013). "Sequencing Y Chromosomes Resolves Discrepancy in Time to Common Ancestor of Males versus Females". Science (New York, N.Y.). 341 (6145): 562–565. doi:10.1126/science.1237619. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 4032117. PMID 23908239.

- ↑ Reich, David (2018). Who We are and how We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past. Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-19-882125-0.

- ↑ White, Tim D.; Asfaw, B.; DeGusta, D.; Gilbert, H.; Richards, G. D.; Suwa, G.; Howell, F. C. (2003), "Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia", Nature, 423 (6491): 742–747, Bibcode:2003Natur.423..742W, doi:10.1038/nature01669, PMID 12802332

- ↑ "Meet the Contenders for Earliest Modern Human". Smithsonian.

- ↑ Fleagle, John G.; Brown, Francis H.; McDougall, Ian (17 February 2005). "Stratigraphic placement and age of modern humans from Kibish, Ethiopia". Nature. 433 (7027): 733–736. doi:10.1038/nature03258. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 15716951.

- ↑ Sahle, Yonatan; Hutchings, W. Karl; Braun, David R.; Sealy, Judith C.; Morgan, Leah E.; Negash, Agazi; Atnafu, Balemwal (13 November 2013). "Earliest Stone-Tipped Projectiles from the Ethiopian Rift Date to >279,000 Years Ago". PLoS ONE. 8 (11). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078092. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3827237. PMID 24236011.

- ↑ Cavalazzi, B.; Barbieri, R.; Gómez, F.; Capaccioni, B.; Olsson-Francis, K.; Pondrelli, M.; Rossi, A.P.; Hickman-Lewis, K.; Agangi, A.; Gasparotto, G.; Glamoclija, M. (1 April 2019). "The Dallol Geothermal Area, Northern Afar (Ethiopia)—An Exceptional Planetary Field Analog on Earth". Astrobiology. 19 (4): 553–578. doi:10.1089/ast.2018.1926. ISSN 1531-1074. PMC 6459281. PMID 30653331.

- ↑ Ehret C, Keita SO, Newman P (December 2004). "The origins of Afroasiatic". Science. 306 (5702): 1680.3–1680. doi:10.1126/science.306.5702.1680c. PMID 15576591.

- ↑ Jason A. Hodgson; Connie J. Mulligan; Ali Al-Meeri; Ryan L. Raaum (12 June 2014). "Early Back-to-Africa Migration into the Horn of Africa". PLOS Genetics. 10 (6): e1004393. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004393. PMC 4055572. PMID 24921250.; "Supplementary Text S1: Affinities of the Ethio-Somali ancestry component". doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004393.s017.

- ↑ David B. Grigg (1974). The Agricultural Systems of the World. C.U.P. p. 66. ISBN 9780521098434.

- ↑ Engels, J. M. M.; Hawkes, J. G.; Worede, M. (21 March 1991). Plant Genetic Resources of Ethiopia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521384568 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Simson Najovits, Egypt, trunk of the tree, Volume 2, (Algora Publishing: 2004), p.258.

- ↑ Pankhurst, Richard K.P. Addis Tribune, "Let's Look Across the Red Sea I"

- ↑ Phoenicia, pg. 199.

- ↑ Rose, Jeanne, and John Hulburd, The Aromatherapy Book, p. 94.

- ↑ Vine, Peter, Oman in History, p. 324.

- ↑ David D. Laitin, Said S. Samatar, Somalia: Nation in Search of a State, (Westview Press: 1987), p. 15.

- ↑ I.M. Lewis, A modern history of Somalia: nation and state in the Horn of Africa, 2nd edition, revised, illustrated, (Westview Press: 1988), p.20

- ↑ Brons, Maria (2003), Society, Security, Sovereignty and the State in Somalia: From Statelessness to Statelessness?, p. 116.

- ↑ Morgan, W. T. W. (1969), East Africa: Its Peoples and Resources, p. 18.