Heng-Nu Jats

Author : Ch. Reyansh Singh

According to Christopher P. Atwood the people mentioned in history as Hiung-nu or Xiong-nu or Hun(a) are non but the same people, i.e. these terms are denoting or referring to the same people (with different names of different regions).[1]

Moreover BS Dahiya wrote, Finally we come to the conclusion that the Chinese name Hiung-nu is correct, after all. These Hiung-nu were a clan dominant at that time. It was this clan which produced emperors like Touman, Maodun, Giya in the first three centuries prior to the Christian era. These Hiung-nu are still existing as a Jat clan in India and are called Heng or Henga. We must remember that the Kang Jat were named by the Chinese as Kang-nu; similarly the Heng were called Heng-nu or Hiung-nu. These were the 'Huna Mandal' rulers who fought with almost all the Indian powers, right up to 10th century A.D.[2] Further BS Dahiya also says, "The Hiung-nu of the Chinese are the Henga Jats of Mathura. The Chinese were right in stating that the Hiung-nu were a part of the Yue-che(Guti) people."[3]

Author's Note- Here mentioned Yueche or Guti people are non But the Jats[4]

"The Chinese author of Thung-Kiang-Nu, writes in the year 555 A.D. that the Aptal or Hephthalites were of the race of Ta-Yue-che."[5][6][7][8][9]

Contents

- 1 Conclusions

- 2 Varients

- 3 The Inter-relation between Hunas, Xiong-nu, Kidarites, Hephthalites and Alchons

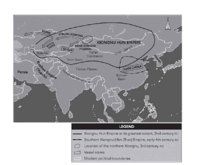

- 4 The Xiong-Nu Empire

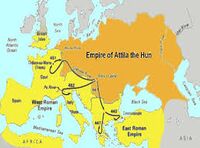

- 5 The Hunnic Empire

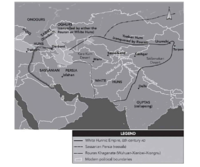

- 6 White Hunnic Empire

- 7 Later/Other Hunnish Principalities

- 8 Rouran Khaganate

- 9 The Xianbei people

- 10 Tiele People & Ashina tribe

- 11 In Traditions of Indian Subcontinent

- 12 Gurjara People

- 13 Monuments

- 14 Clans Originations

- 15 Hunnic Empires in Eurasia

- 16 In Authors Said?

- 17 Notable Persons

- 18 Also see

- 19 Quotes under research

- 20 Note

- 21 References

Conclusions

So, it can be clearly concluded that, Hiungnu or Xiongnu are non but the Henga Jats of India. As it can be clear by the vision of Historian DS Ahlawat as he mentioned(Tr. from Hindi), that "... In chinese language the term 'Henga' is denoted as 'Hingnu'. Which is a Jat clan. ..."[10]

Differentiative People

For The people who tries to create difference between Hiung-Nu or Hunas or Xiongnu, I have a strong material, which is taken from BS Dahiya's epic Jats the Ancient Rulers "... They had a custom of wounding themselves at the time of the funeral of their kings; and Herodotus says that the same custom was observed by the Scythians also. So the Hunas had common customs with the Sakas. Talking about the scripts of various people, the Lalitavistara an Indian work, lists 45 scripts and "Hunalipi" is entered at S. No. 23. The Chinese translated these works and the corresponding entries in the "Fo Pon hing tsi-king" of Jnanagupta (587 A.D.); the "Pou yas king" of Tchu-Fa-hun (308 A.D.), and "Fang Kouang ta Tehouang yen king" of Divakara (683 A.D.)-are Mona, Hiung-nu, and Houna respectively. These are but transcriptions of Mana, and Huna (Kshavan), i.e., the name of Jat clans. This shows that the Chinese knew that all these clans were of the same Yue-che (Gutti) stock and therefore they used the name of the race (Yue-che) or the name of the particular clan which was at that particular time well known to the Chinese authors. These various names were taken, [p.43]: as synonyms of each other. That means that there was no difference between the various clans, racially and linguistically speaking. H. Deguignes, identified the Hiung-nu of the Chinese records with the Huns of Europe, in his five volume Historic general des Huns, des Tures, des mongols, etc., des autres'. From Chinese records, the Russian scholars N.A. Aristov and K. Inostranc-Sev, proved the identity of Hiung-nu and the Hunas. Friedrich Hirth also arrived at the same conclusion as quoted by Dr Buddha Prakash, in "Kalidasa and the Hunas". ...."[11] And Christopher P. Atwood had also proved it by a great effort in "Huns and Xiongnu; New thoughts on an old problems"[1]

Oscar Terry Crosby mentions[12] "It may have been preceded by an intermediate wave of Mongols -the Hueng-nu(Huns) who were the cousins and enemies of the Yue-che."

Remember, that "Otto Maenochen Helforn, in his paper 'Huns and the Hiung-Nu' shows that the Hunas of the Sanskrit works were the Hephthalites. The Chinese author of Thung-Kiang-Nu, writes in the year 555 A.D. that the Aptal or Hephthalites were of the race of Ta-Yue-che."[5]

Author's Note- Remember that Aftal Hephtalite are non, but the Hunas and 'Ta-Yue-Che' is a term to denote "Great Jats"

They were Jats in Origin

Their(Huns') identity has been clarifies as belonging to the Ta-Yue-Che stock of race. [Note, Ta-Yue-Che → Massagetae (or Goths) → "Great" Jats; See, below!]

- According to H.G. Wells, "the Hephthalites (Huns) were descend from the Yueche (Jat) race."[6][13]

- Maenchen-Helfen also noted in his famous monography that despite the fact that the Huns were called Massagetae by the Romans and Greeks.[14]

- Chinese chronicles of "The Weishu chap. 102, p. 2278; Zhoushu chap. 50, p. 918; Beishi chap. 97, pp. 3230–31; and Suishu chap. 83, p. 1854; all wrote that the Hephtalites (Yada in the Weishu, the Zhoushu, and the Beishi Yida in the Suishu) “are a branch of the Da Yuezhi”.[15]

- Tongdian (chinese source, dated ca.801 CE) mention about the Huna/Yada country Yidatong as under, "Yada country, Yidatong: Yada country is said to either be a division of the Gaojgu or of Da Yuezhi stock. They originated from the north of the Chinese frontier and came down south from the Jinshan mountain. They are located to the west of Khotan. To Chang’an, to the east, there are 10,100 li. To the reign of Wen(cheng) of the Late Wei (452–466), eighty or ninety years have elapsed. Their clothing is similar to that worn by other Hu barbarians, [but] with the addition of tassels. They all cut their hair. Their speech is different from that of the Ruanruan, the Gaoju, and all the other Hu. Their troops number perhaps 100,000 men. They wander in search of water and grass. Their country is without the She but has the Yu, and has many camels and horses. They apply punishments harshly and promptly; regardless of how much or how little a robber has taken, his body is severed to the waist, and even though only one has robbed, ten may be condemned. When a person dies, wealthy families pile up stones to make a [burial] vault, while the poor ones simply dig a hole in the ground and bury [the corpse]. All of the deceased’s personal effects are placed in the tomb. Brothers, again, all together marry a wife. Kangju, Yutian, Sule, Anxi and over thirty of the small countries of the Western Regions have all been subjugated by them. They are reputed to be a large country. They often sent envoys bearing tribute. In the Xiping reign period of Xiao Ming Di, Fu Zitong and Song Yun were sent as ambassadors to the Western Regions but were not able to learn much of the history or geography of the countries they traversed.[16]

- The Chinese author of "Thung-Kiang-Nu" stated (in 555AD.) that, "The Aptal or Hephthalites were of the race of Ta-Yue-Che."[5][7][8][9][6]

- Mihirkula - A prominent ruler of Hunas proudly calls himself as the ruler of a "Jit country" as clear by the mentioning in a (Hindi) book, "The Travels of Huen Tsang in India" by Thakur Prasad Sharma (Suresh)[17]

- The traders introduced glassware and pottery in China in the fifth century A.D., when these traders reached the Chinese court of Tai-wee (424-451 A.D.) and informed the Chinese that the Ta-yue-chi (Great Jats) under Ki-to-lo (Kidar, their king) had occupied Peshawar, Gandhara, etc.[18]

- Chinese work Pei-she states, "The Kidarite Hunas(Ki-to-lo) are belonged to the stock of Ta-Yue-Che (Great Jats) race."[19][20]

- The Hephthalites are mentions as belonging to Ta-Yue-che race in Ma-Tuan-Lin's Encyclopedia(around, 1317 AD.)[20] He says that[21] "Ye-ta (Ye-tha = Hephthalites) are of the race of Ta-Yue-Che.

- Historian Zonaras of Rome, in 358 AD mentions these Hunas as "Massagetaens" whom attacked Iran between 353-358 AD (under their king Grumbates).[22] They were Chionites(Xiyon Hunas) who attacked Emperor Shahpur II of Iran, whom were mentions as "Massagetae" by Zonaras.[23][24]

- Roman historians Themistius (317-390), Claudian (370-404), and later Procopius (500-560) called the Huns as Massagetae.[25]

- Edekon or Edica king of Sciri, (during Attila's reign) was interpreted as a Hun by Vigilas to Priscus, sources says that his son Odoacer was a Goth.[26]

- The Huns were called Massagetae also by Ambrose (340-397), Ausonius (310-394), Synesius (373–414), Zacharias Rhetor (465-535), Belisarius (500-565), Evagrius Scholasticus (6th century) and others.[27]

- In the Talmud, Goths are mentions as Gogs, where Magog is the country of Kanths" (Sogdian Kant), that is, the kingdom of the white Huns.[28] i.e., Kingdom of White Huns is mentions as Magog, where Gog is rendered for Goths (Goth → Getae → Jits or Jats).

- In 531 AD, Justinian manages to get hold of intelligence through a spy who had defected from the Persians that the Massagetae had decided to ally with the Persians against the Romans and were marching into Roman territory to join up with the invading Persian army. He, however, cleverly uses this against the Persians and deceives the Persian army besieging Martyropolis into believing that these Massagetae have been won over with money by the Roman emperor. Massagetae here are clearly anachronistic references to the Huns.[29]

- Aigan was a Hun[30][31][32][33] But Procopious in Book 3 of his histories, calls Aigan, the officer in command of Belisarius’ cavalry, a Massagetan by birth.[34] i.e., A leading Hunnic chief[35] namely, 'Aigan' is mentions as a Massagetae by Procopius.

- Christopher P. Atwood concluded that, "The Greek designation of the Ounna(Hun, in Greek), is equivalent as of "Massagetai".[36]

- Chi-Hien of Wu Dynasty (A.D. 222-64) & Dharmaraksha of Western Tsin Dynasty(A.D. 265-313) were actully Huns.[37] And source also states Dharmaraksha as a Yuechi[38][39][40][41] i.e. A buddist monk, Dharamraksha is mentioned as a Hun as well as a Yuchi in history. Also this monk of Hunnic Yuchi origin states the Hun and Hsing-nu as one and same people.[42]

- Classical sources also frequently use the names of older and unrelated steppe nomads instead of the name Hun, calling them Scythians and even "Massagetae"[43]

- Jat Historian Thakur Deshraj also stated that Hingu or Hing-Nu is a branch of Yuechi people.[44]

- The Chinese statement in later Sui-Shu(隋書) that Samarqand's Wen/'On (Hun) dynasty was of Yuezhi, 月氏 (or Jat) origin.[45][46]

- Oscar Terry Crosby mentions[47] in his book in year 1905 that, "Hueng-nu(Huns) were the cousins of the Yuh-chis."

- Author V.P.Desai in his book, "Bharat Ke Chaudhary" (Bharatna Anjana), identifies Haga(Henga clan of Jats) as Hunas.

- The Sakas, the Hunas, called themselves Jats because they were Jats and they never dreamed of changing their names. Therefore, we may say with confidence that Hunas were Indo-Europeans by race, as is supported by recent excavations in Outer-Mongolia, Central Asia and other parts of Asia and Europe.[48]

- Calvin Kephart referring to the Ephthalites, who are called white Hunas, he says, "They were called the white Hunas by their enemies: According to the Chinese, they actually were a tribe of the Yue-chi or Getes" (p. 525 quoting Encyclopaedia Britannica, XIIIth Edn. Vol. IX, p. 679-680, and Vol. XX, p. 422).[49] and two groups of the Massagetae sometime after 500 B.C. took their names as Yue-Chi and White Huns and their later dynastic divisions were called "Kushans".[50]

- Prof. B. S. Dhillon agrees the view and says that Huns (or White Huns) were a branch of the Massagetae or 'great' Jats.[51]

- J.J. Modi says, "The Goths were an offshoot of Huna People."[52]

- Christopher Beckwith also suggested that the name "Huna" is as similar as "Saka"[53]

- Historian BS Dahiya writes[54] ... It is interesting to note that Majumdar and Altekar have pointed out that the so-called white Hunas may possibly be the Kusanas. Similarly Jayaswal also believes that Toraman the conqueror of north India in the beginning of the sixth century A.D., was a Kusana. Historian Fleet holds the same opinion. All these views have been given because really there was no difference between the so-called Hunas and the so-called Kusanas. They were all from the same stock, namely the Jat stock. As shown above the Chinese chronicles are consistent in stating that the so-called White Hunas or the Hephthalites as well as the Kusanas belong to the race of Ta-Yue-che, i.e., the Great Jats.

- Historian DS Ahlawat also agreed to the view, as under[6] "we can accept that Huna and Hephthalites as descends from Jat race."

- With a numerous references and sources G.W. Bowersock mentions, Distinguish Hunnic groups(tribes) as Under: "Goths, Alans, Gepids, Sciri, Sarmatians."[55]

- Vishveshvaranand Indological Journal 1980 (An International Peer-Reviewed Refereed Research Journal) agrees the statement that Henga Jats of Mathura are the Hiung-Nu of the Chinese.[56]

- Even romans identifies them as Scythians and Avars.[55]

- Ivan Georgiev also concluded the same result, that the Huns were descended from Yuechis.[57]

- It is significant that these Hiung-nu (Hunas) were also of Aryan features. This is proved by the portraits of Huna soldiers being trampled under the hooves of the Chinese horses. These Huna soldiers have straight eyes, fine straight noses, and lots of hair and beard-the kind of features which are not possible in case the Hunas were Mongoloids.[58]

- The Utigur Hunnic tribe is identified as Uti tribe clan of Yuechis.[59] Balgur Hunnic tribe is seems to be Bal tribe.

- Author and editor of Bhārati-bhānam (1980), S. Bhaskaran Nair identified The Hiung-nu of the Chinese with present Henga clan of Mathura. he wrote, "Like the Hiung-nu of the Chinese, the present Henga clan occupying about 300 villages near Mathura."[60]

- Author Ramvir Singh Verma postulates, (translated from Hindi) "The Henga Jats migrated from India to China and ruled their for a long time alongside the coasts of Hung-Hu River and Hingu mountains and today known as Henga or Agre or Haga, Hiung-Nu of the Chinese is transcription of term Henga. These Henga Jats named the Hung-Hu River and Hingu Hills in China. They reside in Mathura district of Uttar Pradesh and have more than 360 villages there, the fear and talkings of the empire of Hing-nu people is still prevalent in China.[61]

- A genetic study published in Human Genetics (Journal) in July 2020 which examined the remains of 52 individuals excavated from the Tamir Ulaan Khoshuu cemetery in Mongolia propose the ancestors of the Xiongnu as an admixture between Scythians and Siberians and support the idea that the Huns are their descendants.[62]

- A genetic study published in Nature in May 2018 examined the remains of five Xiongnu. The four samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroups R1, R1b, O3a and O3a3b2, while the five samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroups D4b2b4, N9a2a, G3a3, D4a6 and D4b2b2b. The examined Xiongnu were found to be of mixed East Asian and West Eurasian origin, and to have had a larger amount of East Asian ancestry than neighboring Sakas, Wusun and Kangju. The evidence suggested that the Huns emerged through westward migrations of East Asian nomads (especially Xiongnu tribal members) and subsequent admixture between them and Sakas.[63]

- From the References cited above I, Ch. Reyansh Singh would like to write, that, "The so-called Hun(a)s or Xiong-nu are a branch (Clan) of The Great Ta-Yue-Che race (Great Jats'), which have the very firstly mentions as Houng-nou or Hiung-nu in history. And in India, is still existing as a Jat clan today calls Heng or Henga."

Varients

|

Redirects

- Heng-nu

- Hiungnu

- Hsing-nu

- Xiong-nu

- Hing-nu

- Hingnu

- Hsingnu

- Hing-nu

- Hingu

- Hiung-nu

- Hiang-nu

- Hiyung-nu

- Hiyang-nu

- Huna/Hun

- Heng/Henga

- Hephthalites

- Aftalites

- Huna Jats

- XWN

- XWM

The Inter-relation between Hunas, Xiong-nu, Kidarites, Hephthalites and Alchons

In 1757, Joseph de Guignes first proposed a connection between the European Huns and the Xiongnu on basis of the similarity between the nomadic lifestyles of both peoples[65] and the similarity of their names.[66] In making this equation, de Guignes was not interested in establishing any sort of cultural, linguistic, or ethnic connection between the Xiongnu and the Huns: instead, it was the manner of political organisation that made both "Huns".[67] The equation was then popularized by its acceptance by Edward Gibbon in his The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–1789).[68] David Curtis Wright derives the commonly repeated that the Great Wall of China was built to repel the Xiongnu from a passage in Gibbon.[69] Gibbon argued, from his reading of de Guignes, that the Iranian ("White") and European Huns derived from two distinct divisions of the Xiongnu that survived the destruction of their nation near China.[70] After Gibbon, this thesis quickly became widely accepted among various historians of the Huns.[71] In the late nineteenth century, the classical historian J. B. Bury questioned de Guignes and Gibbon's identification of the Huns with the Xiongnu, arguing that they merely had similar names. He later revised this position, however, and came to accept the link.[72] At the beginning of the twentieth century, German Sinologist Friedrich Hirth discovered passages in the Chinese annals, principally the Wei shu, which he believed proved the connection between the Huns and the Xiongnu.[73] Hirth's work convinced many, and by the 1940s there was a general consensus among historians and archaeologists that the Xiongnu and the Huns were related.[74][75]

By the readings of various article by various authors like, historian Étienne de la Vaissière (2005 and 2015), historian and linguist Christopher Atwood (2012),[1] archaeologist Toshio Hayashi (2014),[76]

Fang Xuanling's Book of Jin lists nineteen Xiongnu tribes: Tuge (屠各), Xianzhi (鮮支), Koutou (寇頭), Wutan (烏譚), Chile (赤勒), Hanzhi (捍蛭), Heilang (黑狼), Chisha (赤沙), Yugang (鬱鞞), Weisuo (萎莎), Tutong (禿童), Bomie (勃蔑), Qiangqu (羌渠), Helai (賀賴), Zhongqin (鐘跂), Dalou (大樓), Yongqu (雍屈), Zhenshu (真樹) and Lijie (力羯).[77]

Etymologically evidences

The chief piece of evidence connecting the Xiongnu to the other Hunnic groups is the apparent similarity of their names. These are recorded in Chinese as Xiōngnú, Greek Οὖννοι (Ounnoi), Latin Hunni, Sogdian Xwn, Sanskrit Hūṇa, Middle Persian Ẋyon and Armenian Hon-k’.[78][79]

- H. W. Bailey believes, "The equivalence of the meaning of Ẋyon to Hun is shown by Syriac use of Hūn to refer to the people called Ẋyon in Persian sources, while Zoroastrian texts in Persian use Ẋyon for the people called Hūṇa in Sanskrit."[80]

- Étienne de la Vaissière has shown that Xiōngnú and the Sogdian and Sanskrit terms Xwm and Hūṇa were used to refer to the same people.[81] He also demonstrates[82] that the Huns who arrived in Europe are from 370 onward called themselves by the name transcribed in the Chinese as "Xiongnu". Also on the same page (p.181) he argued that if the Rhomaioi of Byzantium could claim to be the political heirs of Roman, then the Huns could equally claim to be the heirs of the "Xiongnu".

- According to Schottky Martin, "The Alchon Huns, meanwhile, identify themselves as ALXONO on their coinage, with xono representing Hun: they were identified as Hūṇa in Indian sources."[83]

- Peter B. Golden wrote[84] The Hephthalites identify themselves as OIONO, a version of Hun, on their coinage.

- As per Kim[85] & Golden[86] "the so-called "White Huns" by the Greek historian Procopius and "White Hūṇa" (Śvēta Hūṇa) by Sanskrit authors are same people."

- P. Atwood further mentiones[87] "The Chinese Wei shu attested a title Wēnnàshā for the Kidarite rulers from Bactria who conquered Sogdia, which Christopher Atwood and Kazuo Ennoki interpret as a Chinese transcription of Onnashāh, meaning king of the Huns; the Byzantines also called these people Huns"

- Both de la Vaissière and Kim regard the apparent use of the same name by the European and Iranian Huns as "a clear indication that they regarded this link with the old steppe tradition of imperial grandeur as valuable and significant, a sign of their original identity and future ambitions no doubt".[88]

- The Greeks states the Kidara's as Ounnoi(Hunnic variant in Greek).[89]

- Rezakhani Khodadad, pointing to the Middle Persian apocalyptic book Zand-i Wahman yasn, argued that a name attested there, Karmīr Xyōn ("red Chionites") could represent a translation of Alkhonno, with the first element, al being a Turkic word for red and the second element representing the ethnic name "Hun".[90]

Historical and textual evidences

- The Hephthalites were descendants "of the Gaoju or the Da Yuezhi" according to the earliest chronicles such as the Weishu and the Beishu.[91]

- The 6th-century Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea (History of the Wars, Book I. ch. 3), related Hephthalites to the Huns in Europe.[92]

- Both Denis Sinor and Maenchen-Helfen, meanwhile, note that Ammianus refers to the Huns having been "little known", not unknown, before they appeared in 370: they connect this with a mention of a people called the Khounoi by the geographer Ptolemy in the mid-second century.[93][94]

- A Buddhist Monk, named Zhu Fahu (233-310 AD) translated the ethnonym "Huṇa" from Sanskrit into Chinese as "Xiongnu".[95]

- In contemporaneous sources in India, the Alchons were mentioned as one of the Hūṇa peoples (or Hunas).[96]

- Referring to this Translation by Zhu Fahu(mentioned avobe), Historian Étienne de la Vaissière argues that "the use of the name Huṇa in these texts has a precise political reference to the Xiongnu".[97]

- A second important piece of textual evidence is the letter of a Sogdian merchant named Nanaivande, written in 313 CE; the letter describes raids by the "Xwn"(Sogdiana Huns) on cities in Northern China. Contemporary Chinese sources identify these same people as the Xiongnu.[98]

- De la Vaissière, therefore, concludes that "'Hun/Xwm/Huṇa' were the exact transcriptions of the name that the Chinese had rendered as 'Xiongnu'".[99]

- Another important historical document supporting the identification is the Wei shu. Scholar Friedrich Hirth (1909) believed that a passage in the Wei Shu identified the Xiongnu as conquering the Alans and the Crimea, the first conquests of the European Huns. Otto Maenchen-Helfen was able to show that Hirth's identification of the people and land conquered as the Alans and the Crimea was untenable, however: the Wei Shu instead referred to a conquest of Sogdia by a group that Maenchen-Helfen identified with the Hephthalites, and much of the text was corrupted by later interpolations from other sources.[100]

- However, De la Vaissière notes that a Chinese encyclopedia known as the Tongdian (of 801 CE) preserves parts of the original Wei Shu, including the passage discussed by Hirth and Maenchen-Helfen: he notes that it describes the conquest of Sogdia by the Xiongnu at around 367, the same time that Persian and Armenian sources describe the Persians fighting the Chionites.[101]

- Hyun Jin Kim also mentioned a "general consensus among Historians that the Chionites and the Huns were one and the same".[102]

- A fifth-century Chinese geographical work, the Shi-san zhou ji by Gan Yi, notes that the Alans and Sogdians were under different rulers (the European Huns and the Chionites respectively), suggesting some believed that they had been conquered by the same people.[103]

- Using numismatic evidence, Robert Göbl argued that there were four distinct invasions or migrations of Hunnic people into Persia.[104]

- The people who invaded Iran, are according to Martin Schottky are directly connected to the european Hun.[104]

- De la Vaissière has challenged this interpretation through his use of Chinese sources. He argues that all of the Hunnic groups migrated West in a single migration in the middle of the fourth-century, rather than in successive waves as other scholars have argued. He further argues that "the different groups of Huns were firmly based in Central Asia at the middle of the fourth century. Thus they bring a unity of time and place to the question of the origins of the Huns of Europe".[105]

- Buddhist translator Dharamraksha (Ch. Zhu Fahu, 竺法護), in his translating works of Buddhist sutras namely, Tathagatacintyaguhyanirdesha-sutra (of 288 AD) and Lalitavisatara (of 308 AD) translated the term Hun into chinese as Xiongnu.[106] According to De la Vaissière[107] "As a man of Yuezhi ancestry working at Dunhuang, he would presumably well informed about these things(of translation).

- Around 450 CE, Procopius styled the Hephthalites as White Huns.[108]

- de la Vaissière further notes that according to many later chronicles "the Hephthalites were descends from Yuechi people.[91]

- The Armenian historian Faustus (5th Century) of Byzantium mentions, "Persian King Shahpur II was fighting with Chionite Huns on the eastern front in 358 CE.[109]

Archaeology evidences

The most significant potential archaeological link between the European Huns and the Xiongnu are the similar bronze cauldrons used by the Huns and the Xiongnu. The cauldrons used by the European Huns appear to be a further development of cauldrons that had been used the Xiongnu.[110][111]

- Kim argues that these cauldrons shows that the European Huns preserved the Xiongnu cultural identity.[112]

- Toshio Hayashi has argued that one might be able to track the westward migration of the Huns/Xiongnu by following the finds of these cauldrons.[113]

- Heather notes that both groups made use of similar weapons.[114]

- According to Kim, "the practices of Artificial cranial deformation is used by the Hephthalites and the European Huns, which indicates a connection between them."[115]

- More recent archaeological finds suggest that the first-century so-called "Kenkol group" from around the Syr Darya river performed artificial cranial deformation and might be associated with the Xiongnu.[116]

Ethnographic and Linguistic evidences

- The Xiongnu were bearded people.[117] And the Iranian Huns are also had Beards.[58] and these Iranian Hunas also shaves their beard as mentions in a Sankrit work, Sahitya Darpana.[118]

- As a cultural similarity between Huns of Europe and Xiongnu, we should must remember that they both use to carry a Sword Cult namely Kenglu and "Sword of Mars" in Xiongnu and Hunnic records respectively.[119]

- de la Vaissière considers that the Hepthalites were part of the great Hunnic migrations of the 4th century CE from the Altai region that also reached Europe, and that these Huns "were the political, and partly cultural, heirs of the Xiongnu".[120][121]

- This massive migration was apparently triggered by climate change, with aridity affecting the mountain grazing grounds of the Altay Mountains during the 4th century CE.[122]

- The Hephthalites use to appoint vassal kings in their region as inherited from Xiong-Nu, european Huns also have the similar system of ruling.[123]

Genetics

I thought that after this, all your doubts will be clear; I hope so!

- There is a scientific Journal publishing weekly in London, namely "Nature". According to a genetic study in May 2018, published in it, " the Huns were of mixed East Asian and West Eurasian origin. The authors of the study suggested that the Huns were descended from Xiongnu who expanded westwards and mixed with Sakas."[124][125]

- In November 2019, Neparáczki Endre studied on their DNA reports, and had examined the remains of three males from three separate 5th century Hunnic cemeteries in the Pannonian Basin. They were found to be carrying the paternal haplogroups Q1a2, R1b1a1b1a1a1 and R1a1a1b2a2. In modern Europe, Q1a2 is rare and has its highest frequency among the Székelys. All of the Hunnic males studied were determined to have had brown eyes and black or brown hair, and to have been of mixed European and East Asian ancestry. The results were consistent with a Xiongnu origin of the Huns.[126]

- Christine Keyser found that the Xiongnu shared certain paternal and maternal haplotypes with the Huns, and suggested on this basis that the Huns were descended from Xiongnu, who they in turn suggested were descended from Scytho-Siberians.[127]

- A genetic study published in a Journal namely, "Nature" in May 2018 examined the remains of five Xiongnu. The four samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroups R1, R1b, O3a and O3a3b2, while the five samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroups D4b2b4, N9a2a, G3a3, D4a6 and D4b2b2b. The examined Xiongnu were found to be of mixed East Asian and West Eurasian origin, and to have had a larger amount of East Asian ancestry than neighboring Sakas, Wusun and Kangju. The evidence suggested that the Huns emerged through westward migrations of East Asian nomads (especially Xiongnu tribal members) and subsequent admixture between them and Sakas.[128]

- According to a genetic study published in Journal "Scientific Reports" in november 2019, the remains of three individuals buried at Hunnic cemeteries in the Carpathian Basin in the 5th century AD. The results from the study supported the theory that the Huns (of europe too), were descended from the Xiongnu.[129]

- As per a genetic study published in Journal "Human Genetics" in July 2020 which examined the remains of 52 individuals excavated from the Tamir Ulaan Khoshuu cemetery in Mongolia propose the ancestors of the Xiongnu as an admixture between Scythians and Siberians and support the idea that the Huns are their descendants.[130]

Conclusion

The Huns of Europe are descend from Xiongnu people whom were in India are the Henga Jats.

Then Why History Illustrates an Illusion?

As we have already shown that, The Xiong-nu and Huns were one and same people, even genetically proved; but there stills a numerous varieties of characteristics variations (like, in appearance) found in between them, how could we explain this?

For example, as we have already wrote; with reference to the Sanskrit work "Sahitya Darpana" that, the Iranian Hunas have long beards but what about European Huns? And their Great leader namely "Attila"? As described by Priscus (Greek Historian, 5th Century CE) mentions that Attila had a thin beard.[131]

As for this, I would like to recall the writings of B S Dahiya as under "The Sakas, the Hunas, called themselves Jats because they were Jats and they never dreamed of changing their names. Therefore, we may say with confidence that Hunas were Indo-Europeans by race, as is supported by recent excavations in Outer-Mongolia, Central Asia and other parts of Asia and Europe. But this does not exclude the possibility of some Mongoloid camp followers, or even mixing of blood. We know for certain that a Jat is proverbially liberal in the choice of life partners - he may take as wife a woman from almost any source. Any woman taken by a Jat is called Jatni, (Jāṭ Ke Āai, Jāṭni Kahalāi)."[132]

Here, author Dahiya mentions a very important notice that the Inter-caste marriage or marrying in another ethnicity was not only a Jat custom but of Aryans too, due to which, when these people reaches to different places and established different Dynasties were persistently taking Queens/Wives from other tribes as their ancestral traditions; So, it's quite obvious of variation (in appearance) between the same people of different regions.

For whom, that still having doubts, let me ask, does you and your brother or sister (same as your gender) were looking identicals to each other? Obviously not, So for the authors whom they tried to differentiate between Huns, Kidar(ite)s, Hephthalites, and Xiong-nu on the basis of their appearance, I would like to ask the same question. If there is a lot of difference between Father and his own Son, then how could these people (Huns) have similar Faces? Whom actually taking girls from other tribes too?

Point to be noted is whether, the mother and father belongs to same ethnicity dose not matters as, if we take an example of nowadays; I would like to ask that how many people belongs to a pure stock (i.e., mother, father and even ancestors have same ethnicity), are looking similar in their appearance? This is because that the mother and father both belongs to different Sects (Gotras) of same ethnicity, i.e., of different in their clan/blood in "Jats" this is the reason that why father and his children looks so differ from each other (because, child gets heritage traits from both Father and Mother, so they looks differ from both), these variations are occurs during the process of Zygote formation, a fact well known.

Leave their appearance and have a look towards their traditions, i.e., same weapons, cauldrons, transcription by ancient people etc. So, we could finally concludes that, the Huna and Xiong-nu were one and the same people, belonging to the race of Ta-Yue-che, which means Great Jats.

Further Readings in their relation

- “The Steppe World and the Rise of the Huns,” in M. Maas (dir.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Cambridge, 2014, p. 175-192 by Etienne de la Vaissière

- Kim, Hyun Jin (2013). The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107009066.

- Christopher P. Atwood's "Huns and Xiongnu, New Thoughts on an old Problem"

- Y-chromosome haplogroups from Hun, Avar and conquering Hungarian period nomadic people of the Carpathian Basin - A genetic study.

The Xiong-Nu Empire

Shanyi-yu(Chan-yu) was their Title (adopted) meaning, "The Great Chief"[134] and Shao means King(p.31)

List of rulers

00. Touman - not a Chanyu → 01. Modu, 201-174 BC → 02. Laoshang, 174-160 BC → 03. Junchen, 160-127 BC → 04. Yizhixie, 127-114 BC → 05. Wuwei, 114-104 BC → 06. Zhanshilu, 104-102 BC → 07. Goulihu, 102-101 BC → 08. Judihou, 101-96 BC → 09. Hulugu, 96-85 BC → 10. Huyendi, 85-70 BC → 11. Xulüquanqu, 70-60 BC → 12. Woyenqudi, 60-58 BC → 13. Huhanye, 58-31 BC → 14. Zhizhi, 56-36 BC → 15. Fuzhulei Ruodi, 30-20 BC → 16. Souxie Ruodi, 20-11 BC → 17. Cheya Ruodi, 11-7 BC → 18. Wuzhuliu Ruodi, 7 BC-AD 14 → 19. Wulei Ruodi, AD 14-19 → 20. Huduershidaogao Ruodi, AD 19-47 →

Rulers of the Northern Xiongnu: 21. Punu, AD 47-84 → 22. Sanmulouzhi, AD 84-89 → 23. Yuchujian, AD 89-93 → 24. Aojianrizhuwangfenghou, AD 93-123 →

Rulers of the Southern Xiongnu: 01. Huhanye, AD 48-56 → 02. Chufuyudi, AD 56-58 → 03. Yifayuliudi, AD 58-59 → 04. Xiandongshizhuhoudi, AD 59-63 → 05. Qiuchuzhulindi, AD 63-64 → 06. Houyeshizhuhoudi, AD 64-85 → 07. Yituyuliudi, AD 85-88 → 08. Xiulanshizhuhoudi, AD 88-93 → 09. Anguo, AD 93-94 → 10. Tingdushizhuhoudi, AD 94-98 → 11. Wanshishizhuhoudi, AD 98-124 → 12. Wujihoushizhudi, AD 124-128 → 13. Chuderuoshizhuzi, AD 128-140 → 14. Cheniu, AD 140-143 → 15. Hulanruoshizhuzi, AD 143-147 → 16. Yilingshizhujiu, AD 147-172 → 17. Tuderuoshizhujiu, AD 172-178 → 18. Huzhen, AD 178-179 → 19. Qiangqiu, AD 179-188 → 20. Techishizhuhou, AD 188-195 → 21. Hushuchuan, AD 195-216 → 22. Liubao, AD 216-279 → 23. Liuyuan, AD 279-304.

Source- Article "The Xiongnu Empire" written by the author Ihsan. (2015)

Former Zhao Dynasty

Besides Liuhan, the former Zhao, later Zhao, northern Liang, and Daxia were established by Xiongnu descendants[135]

Though Liu Yuan's own ethnicity, especially whether he was a “pureblood” Xiongnu person, is open to debate, the Former Zhao has been generally regarded as a Xiongnu regime.[136]

Later Zhao

The founder of this dynasty was Shi Le, who was according to book of Jin, was a descend from multi-ethnic Xiongnu tribe known as Qiāngqú (羌渠).[137]

Northern Liang Dynasty

It was founded by Juqu clan of Xiong-nu tribe.[138]

Xia Kingdom

The Xia Kingdom during the rule of Sixteen Kingdoms in China was established by Helian Bobo.

The Hunnic Empire

A Huge Empire From about 370 to 469A.D. stands through over the Central Asian region of Steppe to modern Germany, althrough also extendedly stretched from Danube River to Baltic Sea. Ancient accounts suggest that the Huns had settled in the lands north-west of the Caspian Sea as early as the 3rd Century. By the latter half of the century, about 370, the Caspian Huns mobilized, destroying a tribe of Alans to their west. Pushing further westward the Huns ravaged and destroyed an Ostrogothic kingdom. In 395, a Hun raid across the Caucasus mountains devastated Armenia, there they captured Erzurum, besieged Edessa and Antioch, even reaching Tyre in Syria.

In 408, the Hun Uldin invaded the Eastern Roman province of Moesia but his attack was checked and Uldin was forced to retreat. The Huns were excellent archers, firing from their horses. They engaged in hand to hand combat wearing heavy, strong armor. They employed fake retreat and ambush tactics. They preferred fighting on flat grounds (steppe) where they could maneuver their horses and fire their arrows upwards to rain down on the enemy from above, sitting low on the horse to do so. They are said to have slept and eaten on horseback.

From 420, a chieftain named Oktar began to weld the disparate Hunnic tribes under his banner. He was succeeded by his brother, Rugila who became the leader of the Hun confederation, uniting the Huns into a cohesive group with a common purpose. He lead them into a campaign in the Western Roman Empire, through an alliance with Roman General Aetius. This gave the Huns even more notoriety and power. He planned a massive invasion of the Eastern Roman Empire in the year 434, but died before his plans could come to fruition. His heirs to the throne were his nephews, Bleda and Attila, who ruled in a dual kingship. They divided the Hunnic lands between them, but still regarded the empire as a single entity.

Bleda died in 445 CE. & Attila rules the empire then till his death in 453 CE.

Kings of the Huns

List of kings and ruler of european Hunnic Empire with reigned timeline.

- Balamber/Valamir (died circa 345C.E.)

- Uldin (390-411 C.E.)

- Donatus (d 412 C.E.)

- Charato (411-430C.E.)

- Octar (d. 431 C.E.)—Shared power with Rua.

- Rua/Ruga (d. 434 C.E.)—Sole ruler in 432

- Bleda (434- 445 C.E.) Dual kingship with Attila

- Attila (434-453 C.E.)

- Ellac (453-455 C.E.)

- Dengizik (d. 469 C.E.)

Great Attila

Main article: Attila

Attila(r.434-March 453A.D.) was KIng of the Huna Jats from 434A.D. to his death in March 453A.D. According to an accreditation he was born in 406 A.D. but in support of this, no official records are available for any justification. Hence it's just an accreditation!

His Father was named as, Mundzuk brother of rulers Uldin and Octar and Attila's elder brother was Bleda.

Attila was a great ruler, under him the Hunas had shaken over the roots of both of the Roman Empires.

According to Capt.DS Ahlawat, "Attila was descend from Jat Chief Balamir Hun and having connection with the branch of Jats to which the Indo-Scythians had connected."[139]

Author Michael A. Babcock writes in his famous book 'The Night Attila Died' that, "Before Saddam, before Hitler, before Napoleon— there was Attila. “Born to shake the nations,” the feared and reviled leader of the Huns cut a wide and bloody swath of death and destruction across fifth-century Europe".

White Hunnic Empire

As per author Kim, "Furthermore possessed the familiar Xiongnu Hun system of appointing vassal kings (a practice also found among the European Huns), e.g. the king of Zabulistan who ruled an almost autonomous fief within the empire and was instrumental in spearheading the Hephthalite conquest of northwestern India. As in the old Xiongnu Empire collective governance of the state was practised by several high ranking aristocrats (with new titles such as yabghus (borrowed probably from either the Kangju or Kushans) and tegins). In India the Kidarites and then the Hephthalite Huns also introduced the rule of multiple rajas who held territories in ‘fief ’ to their common overlord the Hunnic supreme king or emperor. Thus a form of quasi-feudalism was introduced to India and a transformation in the administration of revenues took place. The Kidarites are known to have created conditions favourable to international trade and they maintained the monetary and economic system of the regions they conquered without disturbing them. In fact Hunnic rule of Central Asia marked the beginning of the golden age of Sogdian cities such as Samarkand, Bukhara, Paykend and Panjikent, which in many ways exposes the hollowness of the legend of Hunnic ‘destructiveness’. In Khwarezm (northwestern Uzbekistan) at sites such as Barak-tam Hunnic rulers erected two-storey castles with ceremonial halls and carpets in a style that is, according to the great Inner Asian archaeologist Tolstov who excavated the site, distinct and different from previous local structures. The symbiosis and also dichotomy between the dominant ruling steppe pastoralist, i.e. the Huns who constituted much of the imperial army and high-ranking nobility, and the conquered sedentary local population seems to have persisted throughout the Hunnic period (both Kidarite and Hephthalite). However, the upper elite of the White Huns seems to have adapted to local conditions and traditions fairly quickly, readily absorbing elements of Kushan-Indian, Sassanian Persian and Sogdian cultures, especially in their art and architecture. Many Hephthalites, as Litvinsky has shown, were also only semi-nomadic/pastoralists as evidenced by archaeological sites such as the town of Kafyr-qala (southern Tajikistan) in which large quantiies of Hephthalite coins, sealings and even inscriptions have been discovered, clearly indicative of an extended Hephthalite presence. The famous giant Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan, which tragically were destroyed by the infamous Taliban, were probably built under White Hunnic rule and these Buddhas together with other marvellous artefacts discovered in the same area are a testament to White Hunnic religious pluralism, cultural sophistication and cosmopolitanism. The coinage of the White Huns shows an astonishing multi-lingualism employing legends inscribed in

Sogdian, Middle Persian, Bactrian and Brahmi. The Hephthalites are also known to have used Bactrian, Pahlavi, Kharosthi and Brahmi. Like the Hunnic-Germanic kings of Europe, Huns of Central Asia were keen to present themselves as legitimate heirs to the preceding rulers of the regions they conquered. In the case of the Kidarites in particular, as mentioned briefly above, the legacy of the Kushans seems to have been treated with particular care and attention, so much so that these Hunnic kings claimed to be the heirs to the Kushan kings. The rhetoric of the restoration of the Kushan state may have been a very clever propaganda tool employed by the Kidarite Huns to gain the loyalty of their new subjects. Just a century prior to the Hunnic arrival the Kushans had been overwhelmed by the Persian Sassanians. The propaganda suited the new Hunnic conquerors well and gave them a certain legitimacy in the eyes of the local population.

HUNNIC IMPACT ON IRAN AND INDIA

"The conquest of the White Huns had a lasting impact on the histories of both Iran and India. The Sassanian Persians suffered not only military humiliation and vassalage at the hands of the Huns, but also as a direct consequence of their defeats suffered a crisis of legitimacy. Before the Hunnic period the Sassanians had legitimated their overthrow of the preceding Parthian Arsacid dynasty and their usurpation of royal power by appealing to their record of military success against the Romans. Victory over the traditional aggressor (Rome), which had repeatedly sacked the Iranian capital of Ctesiphon in the second and third centuries AD and against whom the Arsacids had been increasingly impotent, was held up as the legitimizing standard of the new Sassanian dynasty. However, the embarrassing defeats suffered by the Sassanians at the hands of the Huns and the reality of the self-proclaimed ruler of both Iran and non-Iran, the Sassanian king, having to play second fiddle and pay tribute to his Hunnic overlord seriously shook the very foundations of Sassanian legitimacy based on the notion of being the victorious defender of a superior Iran against foreign enemies. The Sassanians had to come up with a new ideology to buttress their legitimacy in the eyes of the Iranian aristocracy and people. What appeared was the ‘national’ history (or rather propagandistic pseudo-history) of Iran constructed around the mythical deeds of the legendary forebears of the Sassanians, the Kayanian kings. This legendary history was recast and reshaped to address pressing contemporary concerns. The Sassanians manipulated the traditional religion of Iran, Zoroastrianism, to reinvent themselves as the legitimate descendants of the legendary Kayanian kings, whom they argued were universal kings from whom even the Romans were ultimately derived. The eventual triumph of the Kayanians, after many hardships, in these legends over their arch enemies the Turanians (now equated with the Turkic peoples threatening Iran to the east, i.e. the Kidarite and Hephthalite Huns) helped alleviate somewhat the humiliating reality of Sassanian vassalage to the Huns and excuse the devastating defeats of the king of kings at the hands of the Huns. The reasoning being that the great holy Kayanians had to undergo a similar ordeal. What mattered was ‘legitimacy’. In India, as mentioned briefly above, the Kidarite and Hephthalite invasions led to the creation of a new political order. The enigmatic, possibly Hunnic states of western India and Afghanistan like the Turk Shahi realm of Kabul and Gandhara also effectively blocked the invasions of the Arab Muslims into India from the northwest. Although it is not certain, it also seems likely that the formidable Gurjara Pratihara regime (ruled from the seventh–eleventh centuries AD) of northern India, had a powerful White Hunnic element. The Gurjara Pratiharas who were likely created from a fusion of White Hunnic and native Indian elements ruled a vast empire in northern India and they also halted Arab Muslim expansion into India via Sind for centuries, thereby safeguarding India’s Hindu religion and cultural traditions from Islamization. The Muslims would eventually break through under the Turkic Ghaznavids when both the Shahis and the Gurjaras began to decline in the tenth century AD. However, by then the militant process of conversions of most of the Near East and the Iranian world, a characteristic feature of the early Caliphate (Rashidun and Umayyad), was a thing of the past and India’s religious and cultural universe, despite the imposition of Muslim overlords, was able to persist and survive the conquest. The Huns of India and their descendants may have contributed to the preservation of India’s Hindu civilization and culture from Islamization. Some of the Hunas (Huns) in India also seem to have been instrumental in the formation of the Rajputs.[141]

Kidarite Huns (Red Hunas)

The Kidarites, or Kidara Huns, were a dynasty that ruled Bactria and adjoining parts of Central Asia and South Asia in the 4th and 5th centuries. From 320 to 467 C.E.

The Kidarites established the first of four major Xionite/Huna states in Central Asia, followed by the Alchon, the Hephthalites and the Nezak.

According to Priscus, the Sasanian Empire was forced to pay tribute to the Kidarites, until the rule of Yazdgird II (ruled 438–457), who refused payment.[142]

The Kidarites based their capital in Samarkand, where they were at the center of Central Asian trade networks, in close relation with the Sogdians. The Kidarites had a powerful administration and raised taxes, rather efficiently managing their territories, in contrast to the image of barbarians bent on destruction given by Persian accounts.[143]

Chinese sources explain however that the Kidarites are the Lesser Yuezhi, which would make them relatives of the Yuezhi, themselves ancestors of the Kushans.[144]

The Sasanian efforts were disrupted in the early 5th-century by the Kidarites, who forced Yazdegerd I (r. 399–420), Bahram V (r. 420–438), and/or Yazdegerd II (r. 438–457) to pay them tribute.[145]

The 5th century Byzantine historian Priscus called them Kidarites Huns, or "Huns who are Kidarites"[146]

Lists of Kidarite rulers

| Yosada | c.335 CE |

| Kirada | c.335-345 |

| Peroz Kidarite | c.345-350 |

| Grumbates | c.353-359 |

| Kidara | c.350-390 r.360-388 |

| Brahmi Buddhatala | fl. c. 370 |

| (Unknown) | fl. 388/400 |

| Varhran (II) | fl. c. 425 |

| Goboziko | fl. c. 450 |

| Salanavira | mid 400s |

| Kunkhas | ca.460s |

| Vinayaditya | late 400s |

| Kandik | early 500s |

- The first known rulers of Kidarites was Kirada (reign. 335-345 CE) of Gandhar in Northwestern-India and Yosada/Yasada both Kidarite rulers ruled together.[147] Altogether they form the first coin issues after the reign of the last Kushan ruler Kipunada (335CE)[148]

Kirada was succeeded by Peroz (Kidarite)

Peroz Kidarite & Grumbates

Peroz Kidarite was preceded by Kirada as the new ruler of the Kidarite dynasty. He ruled from 345-353 CE. He minted his own coinage and used the title of Kushansha, ie "Kings of the Kushans"[149] As per Khodadad Rezakhani suggestion, Peroz Kidarite was at the Siege of Amida (present, Diyarbekir, Turkey) in 359 CE, where a Kidarite army under Grumbates is known to have supported the Sassanian army of Shapur II in besieging the city held by the Romans.[150] The coins of Peroz Kidarite founded up to 360 CE; i.e., before the rule of Kidara I but it has to noted that we find mentions of a Xiyon Ruler providing leadership to the Kidarites from 353 to 359 CE against the Sassanids' eastern front. And per Rezakhani[151] Peroz Kidarite was in the siege of Amida 359 CE but those Huns/Chionites were led by Grumbates. We can clearly say that Peroz Kidarite was the rightful heir of the Kidarite throne after the their first known ruler Kirada in 350 CE, but Grumbates is the new ruler may chosen by Hunas or he may forcefully took the leadership, however the suitable theory should be that Grumbates was chosen as a new leader in 353 and continued the coins issued by the Peroz Kidarite. As he should be more capable than Peroz Kidarite as a ruler? This theory is more relievable because we finds mentions in 359 CE they both took arms in a same battle "Siege of Amida" from same side in which the leader was Grumbates and Peroz Kidarite was part of Hunnic army. Now if Grumbates have taken the rule forcefully it is not likely to be easily accept the fact that they both fought together along with Sassanids against the Romans. Grumbates may be a descend from the Kidarite ruler Yosada (ca.335 CE). He was a king of Chionites (Huns) from 353 AD to 358/9 AD, and his tribe, that is Chionitæ said to have come from Transoxiana. As per Ammianus Marcellinus, he was the king of the Chionitae, a man of moderate strength, it is true, he has certain greatness of mind and distinguished by the glory of many victories.[152]

This, Grumbates was a chief/king of Chionites (Huns) whom first attacked Sassanian emperor Shahpur II between 353 AD and 358 CE, the Xionites under Grumbates attacked in the eastern frontiers of Shapur II's empire along with other nomad tribes. However Xiyonites agreed to support Emperor Shahpur II against the romans at Siege of Amida 359 CE. They were first described by the Roman historian, Ammianus Marcellinus, who was in Bactria during 356–357 CE; he described the Chionitæ as living with the Kushans.[153] Ammianus indicates that the Xionites had previously lived in Transoxiana and, after entering Bactria, became vassals of the Kushans, were influenced culturally by them and had adopted the Bactrian language. They had attacked the Sassanid Empire.[154][155] Ammianus Marcellinus reports that in 356 CE, Shapur II was taking his winter quarters on his eastern borders, "repelling the hostilities of the bordering tribes" of the Xionites and the Euseni, a name often amended to Cuseni (meaning the Kushans).[156][157] Later Shapur II made a treaty of alliance with the Chionites and the Gelani in 358 CE.[158] Here Chionites or Xiyonites were a tribe of the Hunas.[159]

Siege of Amida 359 CE

The siege of Amida has taken place in 359 CE, when the Sassanian Emperor Shahpur II make a decision to invade Roman territories in 359 CE. Amida is a town today known as Diyarbakır, Turkey. It was a strong Roman hold and the walls of the fortress of Amida was made by Roman emperor Contantious II (r.337-361)

Ammianus Marcellinus, a Roman army officer, provided a vivid description of the siege in his work (Res Gestae). Ammianus served on the staff of Ursicinus, the Magister Equitum (master of horse) of the East, during the events of the siege.[160] The son of Grumbates lost his life while inspecting the defences of Amida, was shot and killed with an arrow shot by the city garrison. Ammianus described how Grumbates, outraged at his son's death, demanded revenge from the Romans: he compares the death to that of Patroclus at Troy. The Sassanids began the attack with siege towers and attempted to take the city quickly, but were largely unsuccessful.[161]

After the capture of the city, most of the Roman leaders were executed, the city was sacked, the residential areas were destroyed, and the population was deported to Khuzestan province in Persia. Autumn having arrived, the Persians could advance no further. Aside from having spent the campaign season in the reduction of a single city, Shapur II had lost as many as 30,000 in the siege, and his barbarian allies from the east deserted him due to the heavy casualties.[162]

Kidara

Kidara was the famous and first major ruler of the Kidarite Kingdom, which replaced the Indo-Sasanians in northwestern India, in the areas of Kushanshahr, Gandhara, Kashmir and Punjab.[163] It is thought the Kidarites had initially invaded Sogdiana and Bactria from the north circa 300 CE. Kidara invaded the Indo-Sassanian territories of Turkharistan and Gandhar. He was a Hun(a) descend.[164] He led the Huns from 350 to 390 CE. He ruled as a sovereign ruler from 360 to 385-90 CE. Kidara having established himself in Tukharistan and Gandhara, took the title of Kushanshah which until that time had been used by the rulers of the Indo-Sasanian kingdom.[165] He thus founded the eponymous new dynasty of the Kidarites in northwestern India. The Kidarites also claimed to have been successors of the Kushans, possibly due to their ethnic proximity.[166]

The Kushano-Sasanian ruler Varahran (Bahram Kushashah, ca.330) during the second phase of his reign, had to introduce the Kidarite tamga in his coinage minted at Balkh in Bactria, circa 340-345. The tamgha replaced the nandipada symbol which had been in use since Vasudeva I (Kushan emperor)[167] suggesting that the Kidarites had now taken control, first under their ruler Kirada. [168] Then ram horns were added to the effigy of Varahran on his coinage for a brief period under the Kidarite ruler Peroz, and raised ribbons were added around the crown ball under the Kidarite ruler Kidara.[169] In effect, Varahran has been described as a "puppet" of the Kidarites.[170] By 365, the Kidarite ruler Kidara I was placing his name on the coinage of the region, and assumed the title of Kushanshah. In Gandhara too, the Kidarites minted silver coins in the name of Varahran, until Kidara also introduced his own name there.[171]

Some of the Kidarites apparently became a ruling dynasty of the Kushan Empire, leading to the epithet "Little Kushans".[172]

Kidara Successors

In their Indian territories the Kidarites also issued gold coins based on the model of the Late Kushan dinars with the name of Kanishka (III or, if one follows Göbl, II). The Kidarite coins of this group bear the name of Kidara written in Brahmı script, together with the names of dependent rulers or successors of Kidara, on the obverse. The earliest coins are the early Sogdian issues with the name of Kidara (not earlier than the mid-fourth century).[173]

The original nucleus of the Kidarite state was the territory of Tokharistan (now northern Afghanistan and southern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan), which was previously part of the Kushan Empire and subsequently of the Kushano-Sasanians. The capital of the Kidarites, the city of Ying-chien-shih, was probably located at the ancient capital of Bactria, near Balkh. The lands of the Kidarites were known in Armenian sources as ‘Kushan lands’.

The Pei-shih relates that Kidara, having mustered his troops, crossed the mountains and subjected Gandhara to his rule, as well as four other territories to the north of it. Thus, during Kidara’s reign, the Kidarite kingdom occupied vast territories to the north and south of the Hindu Kush. According to another passage from the Pei-shih, referring to the Lesser Yüeh-chih, the principal city of the Kidarites south of the Hindu Kush was situated near present day Peshawar and called (in its Chinese transcription) Fu-lou-sha (Ancient Chinese, pyəu-ləu-sa, which probably represents Purushapura). Its ruler was Kidara’s son, whose name is not mentioned.[174]

Historians have found it difficult to determine the exact period of Kidara and his successors' reign, one reason being that, from the second half of the third century to the fifth century, news reaching China about events in the Western Regions was generally sporadic and patchy. Li Yennien, the author of the Pei-shih, writes that ‘from the time of the Yan-wei (386–550/557) and Chin (265–480), the dynasties of the “Western Territories” swallowed each other up and it is not possible to obtain a clear idea of events that took place there at that time’. A painstaking textual analysis enabled Enoki (and Matsuda before him) to establish that information about Kidara in the Pei-shih was based on the report of Tung Wan sent to the West in 437. From this we can infer that, although the Chinese sources do not provide any dates in connection with Kidara, the Pei-shih describes the situation as it existed in c. 437. On the other hand, Kidara’s rise to power, the founding of his state and the annexation of the territories to the south of the Hindu Kush (including Gandhara) should be dated to an earlier period, that is to say, some time between 390 and 430, but probably before 410. The Kidarites’ advance to the south-east apparently continued even in the middle of the fifth century. This is indirectly proved by Indian inscriptions depicting the events which befell the Gupta king, Kumaragupta I (413–455), when a considerable portion of central and western Panjab was under Kidarite rule. Thus, it was in the first half of the fifth century that the greatest territorial expansion of the Kidarite state occurred.[175] However, as generally Author Dahiya again gives a beautiful account of the genealogy and succesions made during this period as under, "

The Chinese work Pei-She, refers to a king of a Ta Yue-che (i.e., Great Jats) and called him Ki-to-lo which has been rendered by historians as Kidara, perhaps, because in the Chinese language, 't' is used for 't', 'th', 'd', etc. But, the Chinese name She-ki-lo is rendered as Sakala where both Ki and Lo are rendered as Ka and La. So, Ki-to-lo can be rendered, as Katara with equal justification. In fact the word Kedara, was taken as Ketara in Eastern India, as per Brihat-Kalpa Sutra Bhasya.[176] Paul Pelliot supposed that they (the Kidarites) were a clan of Tukhars (Takkhars), perhaps, because they were settled in Turkharistan area.[177] It is generally agreed that Ki-to-lo (Katara or Kidara) is a dynastic name. In fact, it is a clan name and Katariya Jats are even now found in Rohtak district, e.g., in village Samchana. This is further proved from the Chinese annals Pei She itself as it says that Ki-to-lo, the king, was attacked by Jujuan and further it says that another Ki-to-lo was pressed westwards by the Hiungnu (Hunas or Henga Jats). Again Ki-to-lo is the name of a country whose ambassador visited China in 477 A.D. according to Wei Shu. This is the same story of a clan name used for the king as well as for the people and the country over which he ruled. This thing happened, with Kasvans (Kusanas) the Gorayas, the Takkhars and so on. But the important thing is that this clan name Katara/Kidara, was used for a very long time on coins in Kashmir, by king Pravarasen II, son of Toramana and also in Punjab by kings named Bhasvan, Kusala, Prakasa, Siladitya, Kritavirya, etc., about whom nothing else is known. Only their coins show that they were Kidarites or Katariya Jats. The first Jat king called Ketara/Kidara, when pressed by another Jat tribe, named Janjuan (Jujuan of the Chinese), came to Balkh and from there attacked. India, occupying Gandhara and four other kingdoms, while his son took Purushpura, i.e., Peshawar, before 436 A.D. Altekar however, holds on numismatic evidence, that Kidarites rose to power in about 340 A.D. In 356/57 A.D. Shahpuhr II of Iran attacked them in Gandhara and the Katariya Jats sought help from Dharan Jats under Samudragupta, and in 367/68 A.D. they crushed the power of the Iranian king in a fierce battle. In 375 A.D. the first king Kidara/Kitara was succeeded by his son, named Piru, who extended his power further into India and again Piru is a Jat clan. He was succeeded by Varaharan. Barhana a village in Rohtak district, seems to have been named after him. Piru and Kedar are personal names of many Jats of today."[178]

Tobazini

Tobazini, Gobazini or Goboziko (ca. 450 CE.) was a ruler of Kidarites in southern Central Asia. He is only known from his coinage, found in Bactria and Northern Afghanistan. The legends on his coins are in Bactrian, but they are often difficult to read: a typical legend reads t/gobazini/o šauo "King Tobazini". After Tobazini, the Hephthalites adopted the coinage of Peroz I as their model for their own coinage in Bactria, without inscribing the name of their rulers, contrary to their predecessors the Kidarites and the Alchon Huns.[179] His coins often use a symbol, which is similar as one of the symbols of the Alchon Huns in Gandhara and Kabul (besides), but also the symbol of the Imperial Hephthalites, and is a possible indicator of the control of Samarkand, where it was used extensively in the local coinage.[180]

King Kunkhas, Vinayaditya and Kandik

Kunkhas is a notable name to be found in names of successors of Kidara I, he is mentioned by Priscus as ruling in Balkh in 460s. As per E.V. Zeimal, in 460s "the ruler of the Kidarites was Kunkhas, whose father (the source does not name him) had earlier refused to continue to pay tribute to the Sasanians. Peroz (Sassanian emperor), however, no longer had the strength to continue the eastern campaign; in 464, according to Priscus, the envoys of Peroz turned to Byzantium for financial support to ward off invasion by the Kidarites but it was refused. In an attempt to put an end to the war, Peroz made peace overtures to King Kunkhas, offering him his sister’s hand in marriage, but sent him a woman of lowly birth instead. The deception was soon discovered and Kunkhas decided to seek revenge. He asked Peroz to send him experienced Iranian officers to lead his troops. Peroz sent 300 of these ‘military instructors’, but when they arrived Kunkhas ordered a number of them to be killed and sent the others back mutilated to Iran, with the message that this was his revenge for Peroz’s deception. The ensuing war against Kunkhas and the Kidarites ended in 467 with the capture of their capital city of ‘Balaam’. It appears that the Hephthalites were again Peroz’s allies, as they had been in his struggle with Hormizd for the throne of Iran. This put a final end to Kidarite rule in Tokharistan. After their defeat the Kidarites were probably forced to retreat to Gandhara, where, as previously mentioned, the Hephthalites again caught up with them at the end of the fifth century."[181]

So, the history goes like, Kunkhas's father {may be lord Ularg of Samarkand, see section, Kidarite king Ularg of Samarqand (5th century CE).} refused to pay tributes to the Sassanids; the Sassanian Emperor Peroz was not strong enough to confront with Kunkhas in a single stand battle, and as resulted the envoys of Peroz turned to Byzantium for financial support to ward off invasion by the Kidarites but it was refused in order to avoid war Peroz made peace treaty with the Kidarite ruler Kunkhas in 464/5? And offers his sister's marriage with Kunkhas but sent some other woman, When Kunkhas got to know about this he asked militarry personals from Peroz to train his cavalry however the 300 men sent were mostly killed and few left alive returned with the news that Kunkhas killed rest of men in order to avenge the situation when Peroz sent some other woman by saying that she's his sister. And in 466/7 Peroz with the help of his old allies Hephthalites (a rising power) under their King Mahema, confronted and defeated Kunkhas in 467 CE and captured the Kidara state's capital Baalam (or Balkh) and the King Kunkhas retreated to Gandhara and then may to Kashmir as one of thier successors King Vinayaditya late 5th century CE, coins found in Jammu & Kashmir whose successor was King Kandik (early 5th Century CE). At one point, the Kidarites withdrew from Gandhara, and the Alchons took over their mints from the time of Khingila.[182] By 520, Gandhara was definitely under Hephthalite (Alxono) control, according to Chinese pilgrims.[183] In 477 the Kidarites in Gandhara had sent an embassy to China, but the Chinese pilgrim Sung Yün, who visited Gandhara in 520, noted that the Hephthalites had conquered the country and set up their own ruler. ‘Two generations then passed.’ On this basis, Marshall assumes that the invasion took place earlier (reckoning one generation to be 30 years: 520 – 60 = 460).[184]

Alchon Hunas (White Hunas)

Alchon Huns had established estate Empire during 4th & 6th Century C.E.They were first mentioned as being located in Paropamisus, and later expanded south-east, into the Punjab and central India, as far as Eran and Kausambi. They had Ruled about 370 or 400 to 670 CE. Khingila (c.430 CE) was recognized as the founder of the Empire! The Alchons have long been considered as a part or a sub-division of the Hephthalites, or as their eastern branch[185][186] They were a branch of Hephthalites or White Hunas in the time of Toramana, the Hephthalites in India began to operate independently of the Central Asian branch, though the link between them does not seem to have been broken.[187]

Alcono Huna rulers List

| Ruler | reign |

|---|---|

| anonymous rulers | (370s - 430 CE) |

| Khingila | (c. 430 – 490 CE) |

| Ramanila | (circa. 455 - 490 CE) |

| Mehama | (c. 461 – 493 CE) |

| Javukha/Zabocho | (c. mid 5th – early 6th CE) |

| Lakhana Udayaditya | (c. 490's CE) |

| Aduman | ? |

| Toramana | (c. 490 – 515 CE) |

| Mihirakula | (c. 515 – 540 CE) |

| Pravarasena | (c. 530 – 590 CE) |

| Gokarna | (c. 590/1 – 597 CE) |

| Narendraditya Khinkhila (Toramana II) | (c. 597 – 633 CE) |

| Yudhishthira | (c. 633-666 CE) |

Anonymous rulers

It is believed that Hephthalites (Alkans/Alxono-s) took over Bactria around 370 CE under their anonymous chiefs or Kings, the name of these chiefs have not been inscribed in the history. They took control of Bactria from Sassanians (& Kushano-Sassanids) and Kidarites first the Kidarites took this control around 335 CE, then the Alchon Huns from around 370 CE, who would follow up with the invasion of India a century later, and lastly the Hephthalites from around 450 CE.[188]

Through their coinage of the earlier design has yielded the name Thujana (*Thuṃjina) and is attributed to the first ruler, Tunjina. Then we find coins inscribed Shahi Javukha or Shahi Javuvla.[189]

Khingila

Khingila I (Bactrian: χιγγιλο Khingilo, Brahmi script: Khi-ṇgi-la, Middle Chinese: 金吉剌 Jīnjílà, Persian: شنگل Shengel; c.430-490) was the founding king of the Hunnic Alchono dynasty. Another Hunnic chief/king Khushnavaz (or Akhshunwar, ca.458 CE.) was contemporary with him.

In response to the migration of the Wusun (who were hard-pressed by the Rouran) from Zhetysu to the Pamir region, Khingila united the Uars (Avars) and the Xionites (Xiyon Hunas) in 460AD, establishing the Hepthalite dynasty.

According to the Syrian compilation of Church Historian Zacharias Rhetor (c. 465, Gaza – after 536), bishop of Mytilene, the need for new grazing land to replace that lost to the Wusun led Khingila's "Uar-Chionites" to displace the Sabirs to the west, who in turn displaced the Saragur, Ugor and Onogur, who then asked for an alliance and land from Byzantium. In his coin in the Brahmi script, Khingila uses the legend "God-King Khingila" (or Deva Shahi Khingila).[190] Khingila is also mentioned on a Brahmi inscription, the Talagan copper scroll dated 492/3 CE; as a donator to a Buddhist reliquary stupa.[191]

Around 430 CE King Khingila, the most notable Alchon ruler, and the first one to be named and represented on his coins with the legend "χιγγιλο" (Chiggilo) in Bactrian, emerged and took control of the routes across the Hindu Kush from the Kidarites.[192][193] Coins of the Alchons rulers Khingila and Mehama were found at the Buddhist monastery of Mes Aynak, southeast of Kabul, confirming the Alchon presence in this area around 450-500 CE.[194] Khingila, under the name Shengil, was called "King of India" in the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi.[195]

Ramanila

Ramanila (Lae-lih) (circa. 455 - 490 CE), Chinese ambassador Song Yun visited the Hephthalites/Yetha(s) and mentioned that they had conquered the Gandhar two generations ago. And Lae-lih was there first ruler thus Lae-lih have ruled in the latter half of the fifth century AD. Cunningham regards Lae-lih as the father of Toramana. Ramanila the Huna chief of Zabula is known from some of his coins.[196] From another account we learn that the name of the king was Che-le, not Laelih The word Che-le is the Chinese transliteration of the words, T-shawl, T-shaul or Jaula (Jauvla).[197] Author B. S. Dahiya postulated, "The Chinese sources further say that one, Laelih was made ruler of Gandhara by the Yetha. Now the name Laelih has not come down in coins or other literary works. However, the coins of a king named, Ramanila have been found and these coins are related to this very period. We know that the paramount ruling clan was the Jaula, the 'gotra' of Toramana and Mihiragula. It is also known that the ruler of Gandhara was a Tegin meaning Governor- a subordinate title. From these facts it is easy to conclude that paramount rulers had appointed Ramanila, a Jat of Lalli clan (Laelih of the Chinese) as Governor of Gandhara. Thus we find that 'Sung-yun was correct in naming the ruler of Gandhara but, as often, he gave the clan name and not the personal name of the ruler, the latter being Ramanila of the coins. This however, does not mean that Gandhara, Kabul and Gazni were not under the Jats earlier. We know that up to the first century B.C. it was continuously ruled by them and the Jaulas had only replaced the Kasvan Jats, the so-called later Kushana/Kidarites.[198]

As per author Upendra Thakur, "There is yet another controversy regarding the identity of Toramana. The Ephthalite coins bear the name of a king, Ramanila whose portrait on the. coins is depicted facing left, not right, which speaks of his independent status. Ghirsman identifies this king with Toramana but hardty advances any argument in favour of his contention. It's also suggested by another writer that probably Ramanila flourished earlier than Toramana and founded the new kingdom of Zabulistan in c. 455-56 A.D."[199] As per Cunningham he was father of Toramana.[200] As per scholar Buddha Prakash, "Through coins, however reveals the existence of another King Rāmānīlā who called himself Ramanila, king of Zabul, and whose bust faces the left instead of right on his coins is token of his independent status. It is likely that Rāmānīlā was a predecessor of Toramāna and founded the Jauvla empire while the Hephthalites scored victories over the Sassanids and swept into India under Hepthal II. It is also not unlikely that Rāmānīlā belonged to a family that was different from Toramāna."[201]

Mahema, Lakhana Udayaditya & Adomano

Mehama (Bactrian: Meyam, Brahmi: Me-ha-ma), ruled c.461-493, was a king of Alchon Huns dynasty. He is little known, but the Talagan copper scroll mentions him as an active ruler making a donation to a Buddhist stupa in 492/93.[202] Mehama is named Maha Shahi Mehama (Great Lord Mehama) in the Talagan copper scroll.[203] Mahema ruled as a governor of Sassanian emperor Peroz I (r.459-484 AD) from year 461/2 CE this can be clarified by the a letter in the Bactrian language he wrote in 461-462 CE. The letter comes from the archives of the Kingdom of Rob (in southern Bactria, from 5th-7th century atleast), located in southern Bactria. In this letter he presents himself as, "Meyam, King of the people of Kadag, the governor of the famous and prosperous King of Kings Peroz." Kadag is Kadagstan, an area in southern Bactria, in the region of Baghlan. Significantly, he presents himself as a vassal of the Sasanian Empire king Peroz I.[204]

Mehama (r.461-493) allied with Sasanian king Peroz I (459-484) in his victory over the Kidarites in 466 CE, and may also have helped him take the throne against his brother Hormizd III. It is thought that Mehama, after being elevated to the position of Governor for Peroz, was later able to wrestle autonomy or even independence.[205]

Mahema died in 493 CE and succeeded by Lakhana Udayaditya (r.493-?) and Aduman/Adomano (Mid-late 5th century - Early sixth century ?) in unknown dates of the sixth century CE. Adomano identify himself as the ‘Kings of the East’, a designation quite vague in geographical terms. If we consider the Gandhara region as the center of Alkhan rule, on the basis of the issues of their coins and the written sources, the ‘east’ would mean that rulers such as Zabokho or Adomano indeed ruled over the regions of northern Kashmir, including Srinagar.[206] Kings Mahema, Javukha (Zobocho) and Adumana were sub-kings of the Hephthalite empire under their supreme lord Khingila (r.430-490 CE).[207]

Javukha

Javukha (Brahmi: Ja-vu-kha, Bactrian: Zabocho, or Zabokho) was king of the Alchon Huns, in the 5th century CE. Javukha issued coins in the Bactrian script as well as in the Brahmi, suggesting a regnal claim to areas both north and south of the Hindu Kush, from Bactria to Northern Pakistan.[208] He is described as such in the Talagan copper scroll inscription, where he is also said to be Maharaja ("Great King"), and the "son of Sadavikha". In the scroll he also appears to be rather contemporary with Toramana.[209] the Khwera (Kura) inscription records the construction of the monastery from the reigns of Mahārājādhirāja Torāmaṇa and Saha Jauvlah/Shahī Javukha, showing the contemporary rule of these two authorites. Toramana's title of Mahārājādhirāja (King of Kings), harkening back to an Iranian origin, is different from the title he holds in the Schøyen copper scroll, where he is called devarāja (god-king) while Javukha is called Mahārājā (great king) in the same inscription.[210] Zabokho, the other authority with the title of ‘the King of the East’, issued rare silver coins that were minted over a short period of time. These include a regular Alkhan type, with the king’s bust on the obverse and the fire altar (often obliterated by the ‘blind spot’) on the reverse. The philological correspondence of Bactrian Zabokho and Brahmi Javukha, showing that Javukha/Zabokho were the same authority.[211] Zabokho identify himself as the ‘Kings of the East’, a designation quite vague in geographical terms. If we consider the Gandhara region as the centre of Alkhan rule, on the basis of the issues of their coins and the written sources, the ‘east’ would mean that rulers such as Zabokho indeed ruled over the regions of northern Kashmir, including Srinagar. As per Rezakhani, Javukha son of Sādavikhā was younger than Khingila and Mahema, and Adomano was younger than him (Javukha).[212]

Toramana

Toramana I also called Toramana Shahi Jauvla[213] (Gupta script: Toramāṇa,[214] ruled circa 500-515 CE) was a king of the Alchon Huns who ruled in northern India in the late 5th and the early 6th century CE.[215]

Toramana consolidated the Alchon power in Punjab (present-day Pakistan and northwestern India), and conquered northern and central India including Eran in Madhya Pradesh. Toramana used the title "Great King of Kings" (Mahārājadhirāja), equivalent to "Emperor"[216], in his inscriptions, such as the Eran boar inscription.[217] The Sanjeli (presently in Gujarat) inscription of Toramana speaks of his conquest and control over Malwa and Gujarat. His territory also included Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Kashmir[218] He probably went as far as Kausambi, where one of his seals was discovered. As per the Rīsthal inscription, discovered in 1983, the Aulikara king Prakashadharma of Malwa defeated him.[219] In the Khurā inscription (495-500, from the Salt Range in Punjab and now in Lahore), Toramana assumes the Indian regnal titles in addition to central Asian ones: Rājādhirāja Mahārāja Toramāṇa Shahi Jauvla[220][221] A seal from Kausambi associated with Toramana, bears the title 'Hūnarāja' ("Huna King"),[222] Toramana is also described as a Huna (Hūṇā) in the Rīsthal inscription.[223][224][225]

- In the Gwalior inscription, from northern Madhya Pradesh, India, and written in Sanskrit, Toramana is described as:

- "A ruler of [the earth], of great merit, who was renowned by the name of the glorious Tôramâna; by whom, through (his) heroism that was specially characterized by truthfulness, the earth was governed with justice."