Isle of Man

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Isle of Man is a self-governing British Crown dependency, an island in the Irish Sea between Great Britain and Ireland. The head of state is Queen Elizabeth II, who holds the title of Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Governor. Defence is the responsibility of the United Kingdom.

Variants of name

- Ellan Vannin (Manx) [ˈɛlʲən ˈvanɪn])

- Mann (/mæn/; Manx: Mannin [ˈmanɪn])

- Mannin

- Man

- Mana

- Manu

- Manau

- Mano

- Manaw

- Mona

- Monapia

- Monabia

- Monarina

- Mevania

- Mænavia

- Eubonia

- Eumonia

Location

The Isle of Man is located in the middle of the northern Irish Sea, almost equidistant from England, Northern Ireland, Scotland (closest), and Wales (farthest). It is 52 kms long and, at its widest point, 22 kmes wide. It has an area of around 572 square kilometres .[1] Besides the island of Mann itself, the political unit of the Isle of Man includes some nearby small islands: the seasonally inhabited Calf of Man,[2] Chicken Rock on which stands an unmanned lighthouse, St Patrick's Isle and St Michael's Isle. The last two of these are connected to the main island by permanent roads/causeways.

Jat clans

Name

The Manx name of the Isle of Man is Ellan Vannin: ellan (Manx pronunciation: [ɛlʲən]) is a Manx word meaning 'island'; Mannin (IPA: [manɪn]) appears in the genitive case as Vannin (IPA: [vanɪn]), with initial consonant mutation, hence Ellan Vannin, "Island of Mann". The short form often used in English, Mann, is derived from the Manx Mannin,[3] though sometimes the name is written as Man. The earliest recorded Manx form of the name is Manu or Mana.[4]

The Old Irish form of the name is Manau or Mano. Old Welsh records named it as Manaw, also reflected in Manaw Gododdin, the name for an ancient district in north Britain along the lower Firth of Forth.[5] The oldest known reference to the island calls it Mona, in Latin (Julius Caesar, 54 BC); in the 1st century, Pliny the Elder records it as Monapia or Monabia, and Ptolemy (2nd century) as Monœda (Mοναοιδα, Monaoida) or Mοναρινα (Monarina), in Koine Greek. Later Latin references have Mevania or Mænavia (Orosius, 416),[6] and Eubonia or Eumonia by Irish writers. It is found in the Sagas of Icelanders as Mön.[7]

The name is probably cognate with the Welsh name of the island of Anglesey, Ynys Môn,[8] usually derived from a Celtic word for 'mountain' (reflected in Welsh mynydd, Breton menez, and Scottish Gaelic monadh),[9][10] from a Proto-Celtic *moniyos.

The name was at least secondarily associated with that of Manannán mac Lir in Irish mythology (corresponding to Welsh Manawydan fab Llŷr).[11] In the earliest Irish mythological texts, Manannán is a king of the otherworld, but the 9th-century Sanas Cormaic identifies a euhemerised Manannán as "a famous merchant who resided in, and gave name to, the Isle of Man".[12] Later, a Manannán is recorded as the first king of Mann in a Manx poem (dated 1504).[13]

History

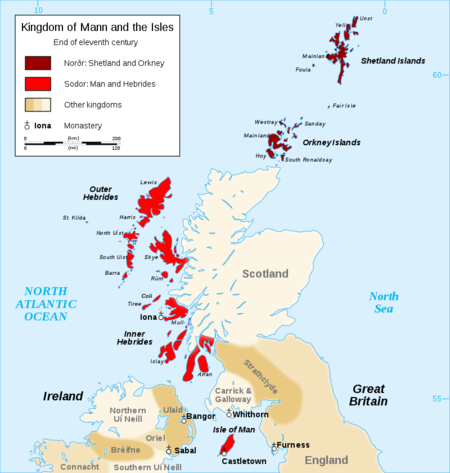

The island has been inhabited since before 6500 BC. Gaelic cultural influence began in the 5th century and the Manx language, a branch of the Gaelic languages, emerged. In 627, Edwin of Northumbria conquered the Isle of Man along with most of Mercia. In the 9th century, Norsemen established the Kingdom of the Isles. Magnus III, King of Norway, was also known as King of Mann and the Isles between 1099 and 1103.[7]

In 1266, the island became part of Scotland under the Treaty of Perth, after being ruled by Norway. After a period of alternating rule by the kings of Scotland and England, the island came under the feudal lordship of the English Crown in 1399. The lordship revested into the British Crown in 1765, but the island never became part of the 18th-century Kingdom of Great Britain or its successors the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the present-day United Kingdom: it retained its status as an internally self-governing Crown dependency.

The island was cut off from the surrounding islands around 8000 BC, and was colonised by sea some time before 6500 BC.[14] The first residents were hunter-gatherers and fishermen. Examples of their tools are kept at the Manx Museum.[15]

The Neolithic Period marked the beginning of farming, and megalithic monuments began to appear, such as Cashtal yn Ard near Maughold, King Orry's Grave at Laxey, Meayll Circle near Cregneash, and Ballaharra Stones at St John's. There were also the local Ronaldsway and Bann cultures.[16]

During the Bronze Age, burial mounds became smaller. Bodies were put in stone-lined graves with ornamental containers. The Bronze Age burial mounds created long-lasting markers around the countryside.[17]

The ancient Romans knew of the island and called it Insula Manavia[18] although it is uncertain whether they conquered the island. Around the 5th century AD, large-scale migration from Ireland precipitated a process of Gaelicisation evidenced by Ogham inscriptions, giving rise to the Manx language, which is a Goidelic language closely related to Irish and Scottish Gaelic.[19]

Vikings arrived at the end of the 8th century. They established Tynwald and introduced many land divisions that still exist. In 1266 King Magnus VI of Norway ceded the islands to Scotland in the Treaty of Perth; but Scotland's rule over Mann did not become firmly established until 1275, when the Manx were defeated in the Battle of Ronaldsway, near Castletown.

In 1290 King Edward I of England sent Walter de Huntercombe to take possession of Mann. It remained in English hands until 1313, when Robert Bruce took it after besieging Castle Rushen for five weeks. A confused period followed when Mann was sometimes under English rule and sometimes Scottish, until 1346, when the Battle of Neville's Cross decided the long struggle between England and Scotland in England's favour.

English rule was delegated to a series of lords and magnates. The Tynwald passed laws concerning the government of the island in all respects and had control over its finances, but was subject to the approval of the Lord of Mann.

In 1866, the Isle of Man obtained limited home rule, with partly democratic elections to the House of Keys, but an appointed Legislative Council. Since then, democratic government has been gradually extended.

External links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queen%27s_House#/map/0

References

- ↑ "Geography – Isle of Man Public Services". Gov.im.

- ↑ Archer, Mike (2010). Bird Observatories of Britain and Ireland (2nd ed.). A&C Black. ISBN 1-4081-1040-7.

- ↑ Jeffcott, J.M. Manx Miscellanies Vol.II, Manx Society, 1880,

- ↑ Kinvig, R. H. (1975). The Isle of Man: A Social, Cultural and Political History (3rd ed.). Liverpool University Press. p. 18. ISBN 0-85323-391-8.

- ↑ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 676. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- ↑ Rivet, A. L. F.; Smith, Colin (1979). "The Place Names of Roman Britain". Batsford: 410–411.

- ↑ Moore 1903:84 Sacheverell 1859:119–120 Waldron 1726:1 Kinvig, R. H. (1975). The Isle of Man. A Social, Cultural and Political History (3rd ed.). Liverpool University Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-85323-391-8.

- ↑ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 676. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- ↑ Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch: Record number 1277 (Root / lemma: men-1)

- ↑ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 679. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- ↑ Kneale, Victor (2006). "Ellan Vannin (Isle of Man). Britonia". In Koch, John T. Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 676.

- ↑ Cited after Catholic World 37 (1883) p. 261.

- ↑ The Dublin Review 57 (1865), 83f.

- ↑ Bradley, Richard (2007). The prehistory of Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-521-84811-3.

- ↑ Manx Museum Mesolithic collections

- ↑ Manx Museum Neolithic collections

- ↑ "Home - Manx National Heritage". Manx National Heritage.

- ↑ Esmonde Cleary, A.; Warner, R.; Talbert, R.; Gillies, S.; Elliott, T.; Becker, J. "Manavia Insula". Pleides. Pleiades.

- ↑ Manx Museum Celtic Farmers (Iron Age) collections