Kuwait

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

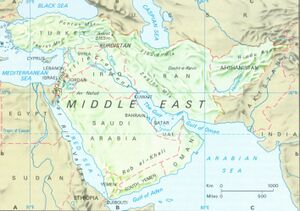

Kuwait (कुवैत) is an Arab country in Western Asia.

Location

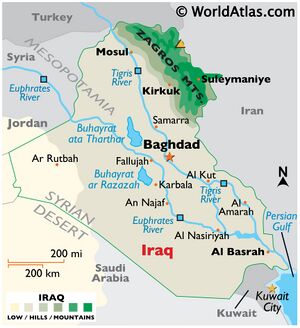

Situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, it shares borders with Iraq and Saudi Arabia.

Etymology

The country's name is from the Arabic diminutive form of كوت (Kut or Kout), meaning "fortress built near water".

History

The geographical region of Kuwait has been occupied by humans since antiquity, particularly due to its strategic location at the head of the Persian Gulf. Historically, most of present-day Kuwait was part of ancient Mesopotamia.[1]

Following the post-glacial flooding of the Persian Gulf basin, debris from the Tigris–Euphrates river formed a substantial delta, creating most of the land in present-day Kuwait and establishing the present coastlines.[2]

One of the earliest evidence of human habitation in Kuwait dates back to 8000 BC where Mesolithic tools were found in Burgan.[3]

Historically, most of present-day Kuwait was part of ancient Mesopotamia.[4]

Kuwait was historically the site of settlements from the Ubaid period (c. 6500 to 3800 BC).[5][6] The earliest evidence of sailing has been found in Kuwait: the world's oldest reed boat was found in Subiya in northern Kuwait.[7]

During the Ubaid period (6500 BC), Kuwait was the central site of interaction between the peoples of Mesopotamia and Neolithic Eastern Arabia,[8] including Bahra 1 and site H3 in Subiya.[9] The Neolithic inhabitants of Kuwait were among the world's earliest maritime traders.[10]One of the world's earliest reed-boats was discovered at site H3 dating back to the Ubaid period.[36] Other Neolithic sites in Kuwait are located in Khiran and Sulaibikhat.[11]

Mesopotamians first settled in the Kuwaiti island of Failaka in 2000 B.C.[12] Traders from the Sumerian city of Ur inhabited Failaka and ran a mercantile business. [13] The island had many Mesopotamian-style buildings typical of those found in Iraq dating from around 2000 B.C.[14]

In 4000 BC until 2000 BC, Kuwait was home to the Dilmun civilization.[15]Dilmun included Al-Shadadiya,[26] Akkaz,[39] Umm an Namil,[16][17] and Failaka.[18] At its peak in 2000 BC, Dilmun controlled the Persian Gulf trading routes.[19]

During the Dilmun era (from ca. 3000 BC), Failaka was known as "Agarum", the land of Enzak, a great god in the Dilmun civilization according to Sumerian cuneiform texts found on the island.[20] As part of Dilmun, Failaka became a hub for the civilization from the end of the 3rd to the middle of the 1st millennium BC.[21] After the Dilmun civilization, Failaka was inhabited by the Kassites of Mesopotamia,[22] and was formally under the control of the Kassite dynasty of Babylon.[23] Studies indicate traces of human settlement can be found on Failaka dating back to as early as the end of the 3rd millennium BC, and extending until the 20th century AD.[24] Many of the artifacts found in Falaika are linked to Mesopotamian civilizations and seem to show that Failaka was gradually drawn toward the civilization based in Antioch.[25]

Under Nebuchadnezzar II, the bay of Kuwait was under Babylonian control.[26]Cuneiform documents found in Failaka indicate the presence of Babylonians in the island's population.[27] Babylonian Kings were present in Failaka during the Neo-Babylonian Empire period, Nabonidus had a governor in Failaka and Nebuchadnezzar II had a palace and temple in Falaika.[28]] Failaka also contained temples dedicated to the worship of Shamash, the Mesopotamian sun god in the Babylonian pantheon.[29]

Following the Fall of Babylon, the bay of Kuwait came under the control of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550‒330 BC) as the bay was repopulated after seven centuries of abandonment.[30] Failaka was under the control of the Achaemenid Empire as evidenced by the archaeological discovery of Achaemenid strata.[31]There are Aramaic inscriptions that testify Achaemenid presence.[32]

In 4th century BC, the ancient Greeks colonized the bay of Kuwait under Alexander the Great. The ancient Greeks named mainland Kuwait Larissa and Failaka was named Ikaros.[33] The bay of Kuwait was named Hieros Kolpos.[34] According to Strabo and Arrian, Alexander the Great named Failaka Ikaros because it resembled the Aegean island of that name in size and shape. Some elements of Greek mythology were mixed with the local cults.[35] "Ikaros" was also the name of a prominent city situated in Failaka.[36]Large Hellenistic forts and Greek temples were uncovered.[37]Archaeological remains of Greek colonization were also discovered in Akkaz, Umm an Namil, and Subiya.[38]

At the time of Alexander the Great, the mouth of the Euphrates River was located in northern Kuwait.[39] The Euphrates river flowed directly into the Persian Gulf via Khor Subiya which was a river channel at the time. Failaka was located 15 kilometers from the mouth of the Euphrates river. By the first century BC, the Khor Subiya river channel dried out completely.[40]

In 127 BC, Kuwait was part of the Parthian Empire and the kingdom of Characene was established around Teredon in present-day Kuwait.[41] Characene was centered in the region encompassing southern Mesopotamia,[42] Characene coins were discovered in Akkaz, Umm an Namil, and Failaka.[43]A busy Parthian commercial station was situated in Kuwait.[44]

The earliest recorded mention of Kuwait was in 150 AD in the geographical treatise Geography by Greek scholar Ptolemy. Ptolemy mentioned the Bay of Kuwait as Hieros Kolpos (Sacer Sinus in the Latin versions).[45]

In 224 AD, Kuwait became part of the Sassanid Empire. At the time of the Sassanid Empire, Kuwait was known as Meshan,[46] which was an alternative name of the kingdom of Characene.[47]Akkaz was a Partho-Sassanian site;[48] the Sassanid religion's tower of silence was discovered in northern Akkaz.[49] Late Sassanian settlements were discovered in Failaka.[50] In Bubiyan, there is archaeological evidence of Sassanian to early Islamic periods of human presence as evidenced by the recent discovery of torpedo-jar pottery shards on several prominent beach ridges.[51]

Most of present-day Kuwait is still archaeologically unexplored.[52] According to several famous archaeologists and geologists, Kuwait was likely the original location of the Pishon River which watered the mythical Garden of Eden.[53] Juris Zarins argued that the Garden of Eden was situated at the head of the Persian Gulf (present-day Kuwait), where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers run into the sea, from his research on this area using information from many different sources, including LANDSAT images from space. His suggestion about the Pishon River was supported by James A. Sauer of the American Center of Oriental Research.[54] Sauer made an argument from geology and history that Pishon River was the now-defunct Kuwait River.[55] With the aid of satellite photos, Farouk El-Baz traced the dry channel from Kuwait up the Wadi Al-Batin.[56]

In 636 AD, the Battle of Chains between the Sassanid Empire and Rashidun Caliphate was fought in Kuwait.[57] At the time, Kuwait was under the control of the Sassanid Empire. The Battle of Chains was the first battle of the Rashidun Caliphate in which the Muslim army sought to extend its frontiers.

As a result of Rashidun victory in 636 AD, the bay of Kuwait was home to the city of Kazma (also known as "Kadhima" or "Kāzimah") in the early Islamic era.[58] Medieval Arabic sources contain multiple references to the bay of Kuwait in the early Islamic period.[92][93][94] According to medieval sources, the city functioned as a trade port and resting place for pilgrims on their way from Iraq to Hejaz. The city was controlled by the kingdom of Al-Hirah in Iraq.[59]In the early Islamic period, the bay of Kuwait was known for being a fertile area.[60] The Kuwaiti city of Kazma was also a stop for caravans coming from Persia and Mesopotamia en route to the Arabian Peninsula. The poet Al-Farazdaq, recognized as one of the greatest classical poets of the Arabs, was born in the Kuwaiti city of Kazma.[61]

Christian Nestorian settlements flourished across the bay of Kuwait from the 5th century until the 9th century.[62] Excavations have revealed several farms, villages and two large churches dating from the 5th and 6th century.[63] Archaeologists are currently excavating nearby sites to understand the extent of the settlements that flourished in the eighth and ninth centuries A.D.[64] An old island tradition is that a community grew up around a Christian mystic and hermit.[65] The small farms and villages were eventually abandoned.[66] Remains of Byzantine era Nestorian churches were found in Akkaz and Al-Qusur.[67] Pottery at the site can be dated from as early as the first half of the 7th century through the 9th century.[68]

In 1613, the town of Kuwait was founded in modern-day Kuwait City. In 1716, the Bani Utubs settled in Kuwait. At the time of the arrival of the Utubs, Kuwait was inhabited by a few fishermen and primarily functioned as a fishing village.[69] In the eighteenth century, Kuwait prospered and rapidly became the principal commercial center for the transit of goods between India, Muscat, Baghdad and Arabia. By the mid 1700s, Kuwait had already established itself as the major trading route from the Persian Gulf to Aleppo.[70]

कुवैत

कुवैत (अरबी: دولة الكويت, दवालात अल-कुवैती) पश्चिम एशिया में स्थित एक संप्रभु अरब अमीरात है, जिसकी सीमा उत्तर में सउदी अरब और उत्तर और पश्चिम में इराक से मिलती है। उत्तर से लेकर दक्षिण तक की अधिकतम दूरी 200 किमी और पूर्व से लेकर पश्चिम तक की दूरी 170 किमी है। कुवैत एक अरबी शब्द है, जिसका अर्थ है पानी के करीब एक महल। करीबन 30 लाख की जनसंख्या वाले इस संवैधानिक राजशाही वाले देश में संसदीय व्यवस्था वाली सरकार है। कुवैत नगर देश की आर्थिक और राजनीतिक राजधानी है। कुवैत में अनेक द्वीप भी शामिल हैं, जिसमें इराक की सीमा से लगा बुमियान सबसे बड़ा है।

1990 में कुवैत पर इराक ने आक्रमण कर कब्जा जमा लिया था। सात महीने का इराकी कब्जा संयुक्त राज्य अमेरिका नीत सेना द्वारा सीधे आक्रमण के बाद खत्म हुआ था। लौटती हुई इराकी सेना ने करीबन 750 तेल के कुंओं को खाक में मिला दिया, जो एक बड़ी आर्थिक और पयार्वरण त्रासदी के रूप में परिणीत हुई। युद्ध में कुवैत की आधारभूत संरचना बुरी तरह से क्षतिग्रस्त हुई, जिसे पुनः सुधारना पड़ा।

तेल भंडारण के मामले में कुवैत दुनिया का पांचवां सबसे समृद्ध देश और प्रति व्यक्ति आय के हिसाब से दुनिया का ग्यारहवां सबसे धनी देश है। कुवैत में तेल क्षेत्र की खोज और दोहन की प्रक्रिया 1930 से प्रारंभ हुई। 1961 में यूनाइटेड किंगडम से स्वतंत्र होने के बाद इस क्षेत्र में अभूतपूर्व वृद्धि दर्ज की गई है। आज देश का करीबन 95 प्रतिशत निर्यात और 80 प्रतिशत सरकारी राजस्व तेल से बने उत्पाद से होती है।

External links

References

- ↑ Sissakian, Varoujan K.; Adamo, Nasrat; Al-Ansari, Nadhir; Mukhalad, Talal; Laue, Jan (January 2020). "Sea Level Changes in the Mesopotamian Plain and Limits of the Arabian Gulf: A Critical Review". Journal of Earth Sciences and Geotechnical Engineering. 10 (4): 88–110.

- ↑ "The Post-glacial Flooding of the Persian Gulf, animation and images". University of California, Santa Barbara.

- ↑ "The Archaeology of Kuwait" (PDF). Cardiff University. pp. 1–427.

- ↑ Sissakian, Varoujan K.; Adamo, Nasrat; Al-Ansari, Nadhir; Mukhalad, Talal; Laue, Jan (January 2020). "Sea Level Changes in the Mesopotamian Plain and Limits of the Arabian Gulf: A Critical Review". Journal of Earth Sciences and Geotechnical Engineering. 10 (4): 88–110.

- ↑ "Kuwait-Polish team finds Ubaid era village". arabtimesonline.com.

- ↑ Carter, Robert (2006). "Boat remains and maritime trade in the Persian Gulf during the sixth and fifth millennia BC". Antiquity 80 (307).

- ↑ "Secrets of world's oldest boat are discovered in Kuwait sands". The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ Carter, Robert (2019). "The Mesopotamian frontier of the Arabian Neolithic: A cultural bor

- ↑ Carter, Robert (2019). "The Mesopotamian frontier of the Arabian Neolithic: A cultural borderland of the sixth–fifth millennia BC". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 31 (1): 69–85. doi:10.1111/aae.12145.

- ↑ Carter, Robert (2011). "The Neolithic origins of seafaring in the Arabian Gulf". Archaeology International. 24 (3): 44. doi:10.5334/ai.0613.

- ↑ Carter, Robert (2019). "The Mesopotamian frontier of the Arabian Neolithic: A cultural borderland of the sixth–fifth millennia BC". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 31 (1): 69–85. doi:10.1111/aae.12145.

- ↑ "Failaka Island - Silk Roads Programme". UNESCO.

- ↑ "Failaka Island - Silk Roads Programme". UNESCO.

- ↑ "Failaka Island - Silk Roads Programme". UNESCO.

- ↑ "Kuwait's archaeological sites reflect human history & civilizations (2:50 – 3:02)". Ministry of Interior News.

- ↑ "Kuwait's archaeological sites reflect human history & civilizations (2:50 – 3:02)". Ministry of Interior News

- ↑ Connan, Jacques; Carter, Robert (2007). "A geochemical study of bituminous mixtures from Failaka and Umm an-Namel (Kuwait), from the Early Dilmun to the Early Islamic period". Jacques Connan, Robert Carter. 18 (2): 139–181. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0471.2007.00283.x.

- ↑ "Kuwait's archaeological sites reflect human history & civilizations (2:50 – 3:02)". Ministry of Interior News.

- ↑ Jesper Eidema, Flemming Højlund (1993). "Trade or diplomacy? Assyria and Dilmun in the eighteenth century BC". World Archaeology. 24 (3): 441–448. doi:10.1080/00438243.1993.9980218.

- ↑ "Sa'ad and Sae'ed Area in Failaka Island". UNESCO.

- ↑ "Sa'ad and Sae'ed Area in Failaka Island". UNESCO.

- ↑ Potts, D.T. (2009). "Potts 2009 – The archaeology and early history of the Persian Gulf". p. 35.

- ↑ Potts, D.T. (2009). "Potts 2009 – The archaeology and early history of the Persian Gulf". p. 35.

- ↑ "Sa'ad and Sae'ed Area in Failaka Island". UNESCO.

- ↑ Tétreault, Mary Ann. "Failaka Island: Unearthing the Past in Kuwait". Middle East Institute.

- ↑ "Brill's New Pauly: encyclopedia of the ancient world". 2007. p. 212.

- ↑ "Brill's New Pauly: encyclopedia of the ancient world". 2007. p. 212.

- ↑ Briant, Pierre (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Pierre Briant. p. 761. ISBN 9781575061207.

- ↑ Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia. Trevor Bryce. p. 198. ISBN 9781134159086.

- ↑ Bonnéric, Julie (2021). "Guest editors' foreword". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 32: 1–5. doi:10.1111/aae.12195. S2CID 243182467.

- ↑ Briant, Pierre (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Pierre Briant. p. 761. ISBN 9781575061207.

- ↑ Andreas P. Parpas. "HELLENISTIC IKAROS-FAILAKA" (PDF). p. 5.

- ↑ Ralph Shaw (1976). Kuwait. p. 10. ISBN 9780333212479.

- ↑ "The European Exploration of Kuwait".

- ↑ Makharadze, Zurab; Kvirkvelia, Guram; Murvanidze, Bidzina; Chkhvimiani, Jimsher; Ad Duweish, Sultan; Al Mutairi, Hamed; Lordkipanidze, David (2017). "Kuwait-Georgian Archaeological Mission – Archaeological Investigations on the Island of Failaka in 2011–2017" (PDF). Bulletin of the Georgian National Academy of Sciences. 11 (4): 178.

- ↑ J. Hansamans, Charax and the Karkhen, Iranica Antiquitua 7 (1967) page 21-58

- ↑ George Fadlo Hourani, John Carswell, Arab Seafaring: In the Indian Ocean in Ancient and Early Medieval Times Princeton University Press, page 131

- ↑ "The Archaeology of Kuwait" (PDF). Cardiff University. pp. 1–427.

- ↑ Andreas P. Parpas (2016). Naval and Maritime Activities of Alexander the Great in South Mesopotamia and the Gulf. pp. 62–11

- ↑ Andreas P. Parpas (2016). Naval and Maritime Activities of Alexander the Great in South Mesopotamia and the Gulf. pp. 62–11

- ↑ Andreas P. Parpas (2016). The Hellenistic Gulf: Greek Naval Presence in South Mesopotamia and the Gulf (324-64 B.C.). p. 79.

- ↑ Farrokh, Kaveh (2007). Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. p. 124. ISBN 9781846031083. "With Babylon and Seleucia secured, Mehrdad turned to Charax in southern Mesopotamia (modern south Iraq and Kuwait)."

- ↑ Reade, Julian, ed. (1996). Indian Ocean In Antiquity. p. 275. ISBN 9781136155314.

- ↑ Gregoratti, Leonardo. "A Parthian Harbour in the Gulf: the Characene". p. 216.

- ↑ "The European Exploration of Kuwait".

- ↑ Hill, Bennett D.; Beck, Roger B.; Clare Haru Crowston (2008). A History of World Societies, Combined Volume (PDF). p. 165. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. "Centered in the fertile Tigris- Euphrates Valley, but with access to the Persian Gulf and extending south to Meshan (modern Kuwait), the Sassanid Empire's economic prosperity rested on agriculture; its location also proved well suited for commerce."

- ↑ Falk, Avner (1996). A Psychoanalytic History of the Jews. p. 330. ISBN 9780838636602. "In 224 he defeated the Parthian army of Ardavan Shah (Artabanus V), taking Isfahan, Kerman, Elam (Elymais) and Meshan (Mesene, Spasinu Charax, or Characene)."

- ↑ Gachet, J. (1998). "Akkaz (Kuwait), a Site of the Partho-Sasanian Period. A preliminary report on three campaigns of excavation (1993–1996)". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 28: 69–79. JSTOR 41223614. "Tell Akkaz in Kuwait.", The Journal of the American Oriental Society

- ↑ Gachet, J. (1998). "Akkaz (Kuwait), a Site of the Partho-Sasanian Period. A preliminary report on three campaigns of excavation (1993–1996)". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 28: 69–79. JSTOR 41223614. "Tell Akkaz in Kuwait.", The Journal of the American Oriental Society

- ↑ Bonnéric, Julie (2021). "A consideration on the interest of a pottery typology adapted to the late Sasanian and early Islamic monastery at al-Qusur (Kuwait)". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 32: 70–82. doi:10.1111/aae.12190. S2CID 234836940.

- ↑ Reinink-Smith, Linda; Carter, Robert (2022). "Late Holocene development of Bubiyan Island, Kuwait". Quaternary Research. 109: 16–38. Bibcode:2022QuRes.109...16R. doi:10.1017/qua.2022.3. S2CID 248250022.

- ↑ "The Archaeology of Kuwait" (PDF). Cardiff University. pp. 1–427.

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier, The Archaeology of the Bible, Lion Hudson: Oxford, England, 34-35; Carol A. Hill, The Garden of Eden: A Modern Landscape.

- ↑ Sauer, James A. (July–August 1996). "The River Runs Dry: Creation Story Preserves Historical Memory". Biblical Archaeology Review. Vol. 22, no. 4. Biblical Archaeology Society. pp. 52–54, 57, 64.

- ↑ Sauer, James A. (July–August 1996). "The River Runs Dry: Creation Story Preserves Historical Memory". Biblical Archaeology Review. Vol. 22, no. 4. Biblical Archaeology Society. pp. 52–54, 57, 64.

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier, The Archaeology of the Bible, Lion Hudson: Oxford, England, 34-35

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier, The Archaeology of the Bible, Lion Hudson: Oxford, England, 34-35

- ↑ Dipiazza, Francesca Davis (2008). Kuwait in Pictures. Francesca Davis DiPiazza. pp. 20–21. ISBN 9780822565895.

- ↑ "Kāzimah". academia.edu.

- ↑ "Culture in rehabilitation: from competency to proficiency". Jeffrey L. Crabtree, Abdul Matin Royeen. 2006. p. 194. "During the early Islamic period, Kazima had become a very famous fertile area and served as a trading stations for travelers in the region."

- ↑ "Farazdaq center lauds Info. Min. care for youth". Kuwait News Agency. 22 May 2014.

- ↑ "Christianity in the Arab-Persian Gulf: an ancient but still obscure history", Julie Bonnéric

- ↑ "Hidden Christian Community". Archaeology Magazine.

- ↑ "Hidden Christian Community". Archaeology Magazine.

- ↑ "Hidden Christian Community". Archaeology Magazine.

- ↑ "Hidden Christian Community". Archaeology Magazine.

- ↑ "Christianity in the Arab-Persian Gulf: an ancient but still obscure history", Julie Bonnéric

- ↑ Vincent Bernard and Jean Francois Salles, "Discovery of a Christian Church at Al-Qusur, Failaka (Kuwait)," Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 21 (1991), 7–21. Vincent Bernard, Olivier Callot and Jean Francois Salles, "L'eglise d'al-Qousour Failaka, Etat de Koweit," Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 2 (1991): 145–181.

- ↑ "Constancy and Change in Contemporary Kuwait City: The Socio-cultural Dimensions of the Kuwait Courtyard and Diwaniyya". Mohammad Khalid A. Al-Jassar. 2009. p. 64.

- ↑ "Constancy and Change in Contemporary Kuwait City: The Socio-cultural Dimensions of the Kuwait Courtyard and Diwaniyya". Mohammad Khalid A. Al-Jassar. 2009. p. 66.