Maldives

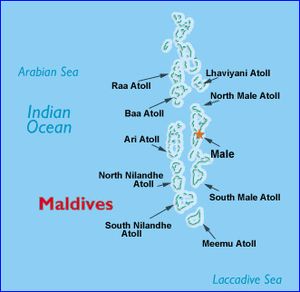

Maldives, officially the Republic of Maldives, is an island nation consisting of a group of atolls in the Indian Ocean.

Contents

Location

The Maldives are located south of India's Lakshadweep islands, and about seven hundred kilometers (435 mi) south-west of Sri Lanka. The twenty-six atolls encompass a territory featuring 1,192 islets, roughly two hundred of which are inhabited by local communities. Islands housing Hotels, antennae, fuel tanks, and other such premises, are not counted as inhabited islands by the administration.

Variants of name

- Mahal Dibiyat (Ibn Batuta)

- Mahiladipaka (Mahavansa/Chapter 6)

- Maladvipa (Sanskrit)

- Mahila dvipa

- Mahiladvipa

- Mahiladiva

Origin of name

The name "Maldives" derives from "Maale Dhivehi Raajje" [The island Kingdom (under the authority of) Male']. A few scholars like to believe that the name "Maldives" derives from the Sanskrit maladvipa, meaning "garland of islands", or from "mahila dvipa", meaning "island of women", but these names are not found in ancient Sanskrit literature. Instead, classical Sanskrit texts mention the "Hundred Thousand Islands" (Lakshadweep); a generic name which would include not only the Maldives, but also the Laccadives and the Chagos island groups. Some medieval Arab travellers like Ibn Batuta called the islands "Mahal Dibiyat" (from Mahal "palace" in Arabic) and this is the name presently inscribed in the scroll of the Maldive State emblem.

The ancient Sri Lankan chronicle Mahawamsa refers to an island called Mahiladiva ("Island of Women", महिलादिभ) in Pali, which is probably a mistranslation of the same Sanskrit word meaning "garland".

Geography

It consists of approximately 1,190 coral islands grouped in a double chain of 26 atolls, spread over roughly 90,000 square kilometers, making this one of the most disparate countries in the world.

For administrative purposes the Maldives government organized these atolls into nineteen administrative divisions.[1]

The largest island of Maldives is Gan, which belongs to Laamu Atoll or Hahdhummathi Maldives.[2] In Addu Atoll the westernmost islands are connected by roads over the reef and the total length of the road is 14 km.

The Maldives has no hills, but some islands have dunes which can reach 2.4 meters above sea level, like the NW coast of Hithadhoo (Seenu Atoll) in Addu Atoll. Islands are too small to have rivers, but small lakes and marshes can be found in some of them.

On average, each atoll has approximately 5 to 10 inhabited islands; the uninhabited islands of each atoll number approximately 20 to 60. Some atolls, however, consist of one large, isolated island surrounded by a steep coral beach. The most notable example of this type of atoll is the large island of Fuvahmulah situated in the Equatorial Channel.

History

A strong underlying layer of Dravidian population and culture survives in Maldivian society, with a clear Dravidian-Malayalam substratum in the language, which also appears in place names, kinship terms, poetry, dance, and religious beliefs. Malabari seafaring culture led to Malayali settling of the Laccadives, and the Maldives were evidently viewed as an extension of that archipelago. Some argue (from the presence of Jat, Gujjar Titles and Gotra names) that Sindhis also accounted for an early layer of migration. Seafaring from Debal began during the Indus Valley Civilisation. The Jatakas and Puranas show abundant evidence of this maritime trade; the use of similar traditional boat building techniques in Northwestern South Asia and the Maldives, and the presence of silver punch mark coins from both regions, gives additional weight to this. There are minor signs of Southeast Asian settlers, probably some adrift from the main group of Austronesian reed boat migrants that settled Madagascar.[3]

The earliest written history of the Maldives is marked by the arrival of Sinhalese people, who were descended from the exiled Magadha Prince Vijaya from the ancient city known as Sinhapura. He and his party of several hundred landed in Sri Lanka, and some in the Maldives circa 543 to 483 BC.

Sinhala history traditionally starts in 543 BCE with the arrival of Prince Vijaya or Singha, a semi-legendary prince who sailed with 700 followers on eight ships 860 nautical miles to Sri Lanka from the southwest coast of what is now the Rarh region of West Bengal.[4] He established the Kingdom of Tambapanni, near modern-day Mannar. Vijaya (Singha) is the first of the approximately 189 native monarchs of Sri Lanka described in chronicles such as the Dipavamsa, Mahāvaṃsa, Cūḷavaṃsa, and Rājāvaliya.

According to the Mahavansa, one of the ships that sailed with Prince Vijaya, who went to Sri Lanka around 500 BC, went adrift and arrived at an island called Mahiladvipika, which is being identified with the Maldives. It is also said that at that time, the people from Mahiladvipika used to travel to Sri Lanka. Their settlement in Sri Lanka and the Maldives marks a significant change in demographics and the development of the Indo-Aryan language Dhivehi, which is most similar in grammar, phonology, and structure to Sinhala, and especially to the more ancient Elu Prakrit, which has less Pali.

Alternatively, it is believed that Vijaya and his clan came from western India – a claim supported by linguistic and cultural features, and specific descriptions in the epics themselves, e.g. that Vijaya visited Bharukaccha (Bharuch in Gujarat) in his ship on the voyage down south.[5]

Philostorgius, a Greek historian of Late Antiquity, wrote of a hostage among the Romans, from the island called Diva, which is presumed to be the Maldives, who was baptised Theophilus. Theophilus was sent in the 350s to convert the Himyarites to Christianity, and went to his homeland from Arabia; he returned to Arabia, visited Axum, and settled in Antioch.[6]

Buddhist period: The Buddhist Stupa (the best preserved, the largest and the last of the Buddhist temples that were destroyed) at Kuruhinna in Gan Island (Haddhunmathi Atoll).

Buddhism came to the Maldives at the time of Emperor Ashoka's expansion, and became the dominant religion of the people of the Maldives until the 12th century AD. The ancient Maldivian Kings promoted Buddhism, and the first Maldive writings and artistic achievements, in the form of highly developed sculpture and architecture, are from that period. Before embracing Buddhism as their way of life, Maldivians had practised an ancient form of Hinduism, ritualistic traditions known as Śrauta, in the form of venerating the Surya (the ancient ruling caste were of Aadheetta or Suryavanshi origins).

The first archaeological study of the remains of early cultures in the Maldives began with the work of H.C.P. Bell, a British commissioner of the Ceylon Civil Service. Bell was first ordered to the islands in late 1879[7] he returned twice to the Maldives to investigate ancient ruins. He studied the ancient mounds, called havitta or ustubu (these names are derived from chaitiya and stupa) (Maldivian: ހަވިއްތަ) by the Maldivians, which are found on many of the atolls. Although Bell asserted that the ancient Maldivians had followed Theravada Buddhism, many local Buddhist archaeological remains now in the Malé Museum in fact also display elements of Mahayana and Vajrayana iconography.

Isdhoo Lōmāfānu is the oldest copper-plate book to have been discovered in the Maldives to date. The book was written in AD 1194 (590 AH) in the Evēla form of the Divehi akuru, during the reign of Siri Fennaadheettha Mahaa Radun (Dhinei Kalaminja).

In the early 11th century, the Minicoy and Thiladhunmathi, and possibly other northern Atolls, were conquered by the medieval Chola Tamil emperor Raja Raja Chola I, thus becoming a part of the Chola Empire.

According to a legend from Maldivian folklore, in the early 12th century AD, a medieval prince named Koimala, a nobleman of the Lion Race from Sri Lanka, sailed to Rasgetheemu island (literally "Town of the Royal House", or figuratively "King's Town") in the North Maalhosmadulu Atoll, and from there to Malé, and established a kingdom. By then, the Aadeetta (Sun) Dynasty (the Suryavanshi ruling cast) had for some time ceased to rule in Malé, possibly because of invasions by the Cholas of Southern India in the 10th century. Koimala Kalou (Lord Koimala), who reigned as King Maanaabarana, was a king of the Homa (Lunar) Dynasty (the Chandravanshi ruling cast), which some historians call the House of Theemuge.[8]

The Homa (Lunar) dynasty sovereigns intermarried with the Aaditta (Sun) Dynasty. This is why the formal titles of Maldive kings until 1968 contained references to "kula sudha ira", which means "descended from the Moon and the Sun". No official record exists of the Aadeetta dynasty's reign. Since Koimala's reign, the Maldive throne was also known as the Singaasana (Lion Throne).[9]

Before then, and in some situations since, it was also known as the Saridhaaleys (Ivory Throne).[10]

Some historians credit Koimala with freeing the Maldives from Chola rule.

Several foreign travellers, mainly Arabs, had written about a kingdom of the Maldives ruled over by a queen. This kingdom pre-dated Koimala's reign. al-Idrisi, referring to earlier writers, mentions the name of one of the queens, Damahaar, who was a member of the Aadeetta (Sun) dynasty.

Following the introduction of Islam in 1153, the islands later became a Portuguese (1558), Dutch (1654), and British (1887) colonial possession. In 1965, Maldives obtained independence from Britain (originally under the name "Maldive Islands"), and in 1968 the Sultanate was replaced by a Republic. However, in 38 years, the Maldives have had only two Presidents, though political restrictions have loosened somewhat recently.

Maldives is the smallest Asian country in terms of population. It is also the smallest predominantly Muslim nation in the world.

Visit of Ibn Battuta

Ibn Batutah (1304 – 1369) , a Moroccan explorer, arrived India in 1333-1334. In 1342 Ibn Batutah leaves Delhi on his mission to China.

From the Rajput Kingdom of Sarsatti, he visited Hansi in India, describing it as "among the most beautiful cities, the best constructed and the most populated; it is surrounded with a strong wall, and its founder is said to be one of the great infidel kings, called Tara".[11]

En route to the coast at the start of his journey to China, Ibn Battuta and his party were attacked by a group of bandits.[12] Separated from his companions, he was robbed and nearly lost his life.[13] Despite this setback, within ten days he had caught up with his group and continued on to Khambhat in the Indian state of Gujarat. From there, they sailed to Kozhikode (Calicut), where Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama would land two centuries later. While Ibn Battuta visited a mosque on shore, a storm arose and one of the ships of his expedition sank.[14] The other ship then sailed without him only to be seized by a local Sumatran king a few months later.

Afraid to return to Delhi and be seen as a failure, he stayed for a time in southern India under the protection of Jamal-ud-Din, ruler of the small but powerful Nawayath sultanate on the banks of the Sharavathi river next to the Arabian Sea. This area is today known as Hosapattana and lies in the Honavar administrative district of Uttara Kannada. Following the overthrow of the sultanate, Ibn Battuta had no choice but to leave India. Although determined to continue his journey to China, he first took a detour to visit the Maldive Islands.

He spent nine months on the islands, much longer than he had intended. As a Chief Qadi, his skills were highly desirable in the formerly Buddhist nation that had recently converted to Islam. Half-kidnapped into staying, he became chief judge and married into the royal family of Omar I. He became embroiled in local politics and left when his strict judgments in the laissez-faire island kingdom began to chafe with its rulers. In the Rihla he mentions his dismay at the local women going about with no clothing above the waist, and the locals taking no notice when he complained.[15] From the Maldives, he carried on to Sri Lanka and visited Sri Pada and Tenavaram temple.

Jats History

There is a sizable population of Jats in Maldives. It is a matter of research how and when Jats came to Maldives.

Jat clans

Notable persons

- Om Prakash Moond - Moh. Maldives Maldives Govt., Date of Birth : 1.2.1979, VPO - Jassi Ka Bass, Teh.- Neem Ka Thana, Dist- Sikar, Rajasthan ,India- 332713, Present Address : TRH, Gdh. Thinadhoo rep. of Maldives, Mo: 9607861596, Email:opmoond@gmail.com

External Links

External Links

Back to Places

- ↑ Muhammadu Ibrahim Lutfee, Divehiraajjege Jōgrafīge Vanavaru. G.Sōsanī. Malé 1999

- ↑ Hasan A. Maniku, The Islands of Maldives. Novelty. Male 1983

- ↑ Maloney, Clarence. "Maldives People". International Institute for Asian Studies.

- ↑ The Mahavamsa

- ↑ Maloney, Clarence. "Maldives People". International Institute for Asian Studies.

- ↑ Philostorgius, Church History, tr. Amidon, pp.41–44; Philostorgius' history survives in fragments, and he wrote some 75 years later than these events.

- ↑ This was in order to care for a shipwrecked British steamer's load. Bell moreover had the chance to spend two or three in Malé, on same occasion. See: Bethia Nancy Bell, Heather M. Bell: H.C.P. Bell: Archaeologist of Ceylon and the Maldives, p.16.

- ↑ "The Lion Throne Coronation Proclamation of King Siri Kula Sudha Ira Siyaaka Saathura Audha Keerithi Katthiri Bovana". Maldives Royal Family. 21 July 1938.

- ↑ "The Lion Throne Coronation Proclamation of King Siri Kula Sudha Ira Siyaaka Saathura Audha Keerithi Katthiri Bovana". Maldives Royal Family. 21 July 1938.

- ↑ "Legend of Koimala Kalou". Maldives Royal Family.

- ↑ André Wink, Al-Hind, the Slave Kings and the Islamic Conquest, 11th-13th Centuries, Volume 2 of Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World. The Slave Kings and the Islamic Conquest 11th-13th Centuries, (BRILL, 2002), p.229.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 215; Gibb & Beckingham 1994, p. 777 Vol. 4

- ↑ Gibb & Beckingham 1994, pp. 773–782 Vol. 4; Dunn 2005, pp. 213–217

- ↑ Gibb & Beckingham 1994, pp. 814–815 Vol. 4

- ↑ Jerry Bently, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993),126.