The Rajas of the Punjab by Lepel H. Griffin/The History of the Jhind State

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (Retd.), Jaipur |

Printed by the Punjab Printing Company, Limited, Lahore 1870

The History of the Jhind State

Contents

- 1 The origin of the family of Jhind

- 2 Alam Singh, the eldest son of Sukhchen

- 3 The family of Gajpat Singh

- 4 Jhind attacked by the Governor of Dehli

- 5 Raja Bhag Singh

- 6 He joins General Ochterlony

- 7 His excesses and their result

- 8 The draft will by which the elder son was dispossessed

- 9 The helpless State of Raja Bhag Singh

- 10 Pratab Singh flies from Jhind to Balawali

- 11 The death of Raja Bhag Singh, 1819

- 12 Raja Sangat Singh installed

- 13 The collateral relatives and the law of escheat

- 14 Division of the ancestral state by the Phulkian Chiefs

- 15 The installation of Raja Sarup Singh AD 1837

- 16 The action of the Raja of Jhind during the war of 1845-46

- 17 His rewards

- 18 Exchange of Dadri villages for others in Hissar

- 19 The precedence of Jhind and Nabha

- 20 The question of precedence

- 21 Ragbhir Singh his successor

- 22 The family of Raja Raghbir Singh

The origin of the family of Jhind

Until the time of Chaudhri Phul (Sidhu - Jat clan), the history of the Pattiala and the Jhind families are the same, and there is no occasion to repeat here what has already been recorded regarding it.* (See:The Rajas of the Punjab by Lepel H. Griffin/The History of the Patiala State)

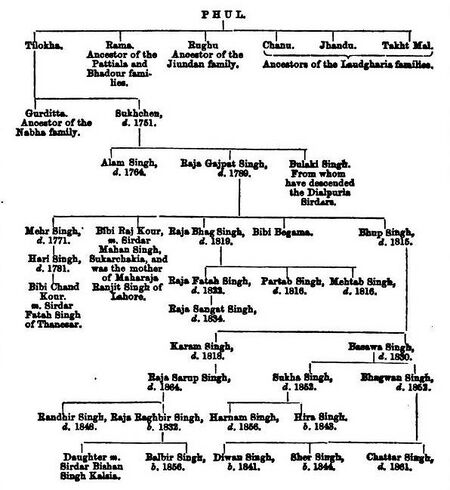

Tilokha, the eldest son of Phul, had two sons, Gurditta and Sukhchen, from the elder of whom has descended the Nabha family, and from the younger the Chiefs of Jhind, Badrukhan and Bazidpur. Tilokha succeeded his father as Chaudhri, but although he thus became the head of the family, he was not a man of any energy, and made no attempt to increase his share of the estate. Sukhchen, the second son, was a simple zamindar, and nothing worthy of record is known of him, except his marriage to Agan, the daughter of Chuhr Singh, a Bhullar Jat of Mandi, who bore him three sons, Alam Singh, Gajpat Singh and Bulaki Singh. He founded several new villages, one of which, called after his own name, he gave to his youngest son Bulaki Singh ; and a second, Balanwali, to Alam Singh. After having made his division of his estate, he continued to reside with his second son Gajpat Singh, at the ancestral village of Phul, where he died, aged seventy-five, in the year 1758.

* Anie, pp. 2-9

The following is the genealogy of the Jhind family (as pictured).

It is with Gajpat Singh that Jhind history is specially concerned, and the briefest notice is required of the other sons of Sukhchen.

Alam Singh, the eldest son of Sukhchen

Alam Singh, the eldest, was a brave soldier, and distinguished himself in many fights With the Imperial troops.

After the conquest of Sirhind, in 1763, he took possession of a considerable tract of country, but was killed the following year by a fall from his

horse. He left no children, though he had married three times. His first wife was of a Gill family of Cholia Chubara, his second the daughter of Man zamindar of Maur Saboki, and the last a girl, Mala by name, whom he had induced to elope from the house of her Either a Dhaliwal zamindar.

Bulaki Singh, the youngest son of Sukhchen, was the ancestor of the Dialpuria Sirdars, of whom a notice has been already given in the chapter on the Minor Phulkian Houses.* He died in 1785.

Gajpat Singh, the " second son, was born about the

year 1783 and grow up a fine handsome youth, well skilled in all military exercises. He lived with his father at

Phul, till the latter's death, assisting him against his rival and brother Gurditta, in whose time commenced the feud between the Jhind and Nabha

houses, which is even now hardly healed. The great subject of dispute was the possession of Rampura Phul, the ancestral village, which each branch of the family naturally desired to own, and to which Chaudhri Gurditta's claims, as head of the Phulkian house, were perhaps the stronger. It was at the instigation of Gurditta, that, in 1743, when Gajpat Singh was five years old, both he and his mother Agan were captured by the Imperial troops and carried prisoners to

Dehli as hostages for Sukhchen, who had fallen into arrears with his revenue collections, and who

contrived to escape the troops sent to seize him.

The mother and child were fortunate enough to

soon escape through the fidelity and courage of one

* Vide ante p. 307.

of Agan's slave girls, who disguised her mistress in her own dress and remained behind in her place in the prison.

The family of Gajpat Singh

Gajpat Singh married, in 1754, one of the widows of his brother Alam Singh, and succeeded to his estate of Balawanli. This wife bore him one daughter, Begama. Previous to this he had married the daughter of Kishan Singh of Monshia, of whom were born four children, Mehr Singh, Bhag Singh, Bhup Singh, and a daughter Raj Kour, who was married to Sirdar Mahan Singh Sukarchakia and became the mother of Maharaja Ranjit Singh of Lahore.

His conquests and misfortunes:

Gajpat Singh joined the Sikh army in 1768, when Zin Khan the Afghan Governor of Sirhind was defeated and slain ; and he then seized a large tract of country, including the districts of Jhind and Safidon, overrunning Panipat and Karnal, but he was not sufficiently strong to hold them. Yet, in spite of this rebellion, he did not deny altogether the authority of the Dehli Court. He remained, as before, a Malguzdr of Dehli, paying revenue to the Emperors; and, in 1767, having fallen a lakh and a half into arrears, he was taken prisoner by Najib Khan, the Muhammadan Governor, and carried to Dehli, where he remained a prisoner for three years, only obtaining release by leaving his son, Mehr Singh, as a hostage for the punctual payment of what was due. He then returned to Jhind, where, after great difficulties and delay, collecting three lakhs of Rupees he carried them to Dehli and not only freed his son, but obtained the title

He obtains the title of Raja AD 1768:

of Raja, under a Royal Firman or grant.* From this time Gajpat Singh assumed the style of an independent prince, and coined money in his own capital.†

The marriage of Raj Kor to Sirdar Mahan Singh:

In 1774, the marriage of Sirdar Mahan Singh Sukarchakia was celebrated with Raj Kour, the daughter of Raja Gajpat Singh, at Bhadra Khan, then the capital of Jhind. The Gujranwala Chief came with a large retinue, and all the Phulkian Chiefs were assembled in honor of the occasion. A trifling incident which occurred during the festivities was the cause of a serious quarrel between Nabha and Jhind. The Sirdar of the former State, Hamir Singh, had a valuable grass preserve or "Bir" in the neighbourhood of Bhadra Khan, in which the Baratis or attendants of the bridegroom, were permitted to cut grass for their horses. But no

* This Firman is dated 25th Shawal 1185 A. H. (A. D. 1772) under the Seal of the Emperor Shah Alam.

† The right of coining 18 a privilege which belongs to independent Chiefs alone, as the term “independent” is technically used in Indian politics.

The following Information regarding the Mints in the three Phalkian States of Pattiaia, Nabha and Jhind, was collected by Major General B. G. Taylor, C. B., C. S. I., Agent to the Lieutenant Governor Cis-Satlej States, at the request of the Foreign Secretary to the Government of India. The only other recognized mints in the States in political dependence on the Punjab Government are in Maler Kotla and Kashmir.

I. Political condition.— No trace is ascertainable of any communication having been held with this office regarding the Mint. The Pattiaia authorities have alluded to an application made, on the occasion of Lord Dalhousie holding a Durbar at Pinjor in 1851, by the Pattiaia Government for permission to remodel the Pattiaia State Mint. To this the Pattiaia Officers say no definite answer was given, and they presume that the record must be in this office, but I have had it searched for without success.

The Mint of Pattiaia is said to have been established by the order of Ahmad Shah Durani, when the Patiala State was ruled by Maharaja Amar Singh, this would have been about 100 years ago; in fact, in another place in the Pattila reports, Sambat 1820 (A. D., 1763 ) is mentioned as the year

sooner had they commenced operations than Yakub Khan, the Agent of Hamir Singh, more zealous than hospitable, attacked them and a fight was the result, of which no notice was taken till after ceremony and departure of the bridegroom.

The quarrel with Nabha:

Raja Gajpat Singh then resolved to avenge the insult, and feigning to be at the point of death, sent to his cousin of Nabha requesting him to come and see him before he died. The unsuspecting Sirdar arrived in haste, with Yakub Khan, and to his great surprise was arrested and placed in confinement, while his officer was put to death. The Raja then sent a force against Imloh and Bhidson, two strong places in Nabha terri-

II. The nature, title and character of the coinage.- The Pattiala rupee is known as the Rajah Shahi rapee ; it is three-fourths of an inch in circumference, and weighs 11-1/4 mashas : it is of pure silver. The coin is really five ruttees less in weight than the British Government rupee, but the amount of actual silver in each is the same, and consequently the Pattiala rupees fetches the full 16 annas, but is subjected some times to arbitrary discount by the shrafhs in British territory, and its value also fluctuates with the value of silver in the markets; fetching in this way some times more than the 16 annas.

The Pattiala Gold-Mohur weighs 10-3/4 mashas, and is of pure gold.

No copper coin is struck in Pattiala.

The inscription on the gold and silver coin is the same : it runs—

- "Hukm shud az Qadir-i-bechun ba Ahmad Badshah

- Sikha zan bar sim-o-zar az ouj-i-mahi ta ba Mah :

- Jahu Meimunut Manus zarb Sirhind,"

The translation of which is : “ The order of God, the peerless, to Ahmad Badshah : Strike coin on silver and gold from earth to heaven," (this is the real meaning of the passage ; the actual words are “ from the height of the fishes back to the moon”) " in the presence, favored of high fortune “ ( here would follow the date ) " the Sirhind coinage."

No alteration has ever been made in the inscription : certain alterations are made in the marks to mark the reign of each Chief.

Thus, Maharaja Amar Singh's rupee is distinguished by the representation of a Kulffi ( small aigrette plume ) ; Maharaja Sahib Singh's by that of a Saif, (or two edged sword) ; Maharaja Karam Singh’s had a Shamsher ( bent sabre ) on his coin ; Maharaja Narindar Singh’s coin had a Katta (or straight sword) as his distinguish mark.

The present Maharajah's rupee is distinguished by a dagger.

The inscription being long, and the coin small, only a small portion of the inscription finds on each coin

tory, and attacked Sangrur, which was defended for four months by Sirdarni Deso, wife of Hamir Singh. At length, seeing her cause desperate, she begged the Raja of Pattiala to interfere. This Chief, who had encourage, the attack in the first place, hoping to weaken both Jhind and Nabha and consequently increase his own power, had no wish to see the former become too powerful, and interposed with other Sikh Sirdars, compelling Raja Gajpat Singh to restore Imloh and Bhadson and release Hamir Singh. Sangrur was retained and has ever since been included in the Jhind territory.

Jhind attacked by the Governor of Dehli

The next year Rahim Dad Khan, Governor of by Hansi, was sent against Jhind by the Dehli Governor Nawab Majad-ul-dowla Abdulahd Khan, and Raja Bhag Singh summoned to his assistance the Phulkian Chiefs.

II. The annual out-turn of the establishment, and the value of the coinage as compared with that of the British Government, — The annual out- turn is in fact evidently uncertain ; the striking of the coin being only capriciously carried out on especial occasions, or when actually wanted.

The officials report that the Pattiala Mint could strike 2,000 coins per diem, if necessary ; always supposing that there be sufficient grist for the mill.

The value, with reference to British Government coin, has been given above in replying to question No. II.

IV. The process of manufacture, and any particulars as to the artificers employed. — The Mint is supervised by a Superintendent, a Mohurrir, two Testers, one Weigher, 10 Blacksmiths, two Coiners, four Refiners of Metal, and one Engraver.

The Metals are refined carefully, and thus brought up to the standard of the gold and silver kept as specimens in the Mint ; the metal is tested and then coined.

The chief implements are anvils, hammers, scales, dies, pincers, vices, &c.

V. The arrangements for receiving bullions and the charges (if any) levied for its conversion into Coin.— Metal brought by private individuals is coined at the following rates : —

Silver, 1 rupee 1 anna for 100 coins, of which the State dues amount to 10-1/2 annas, and 6-1/2 go to the establishment.

Raja Amar Singh of Pattiala, who sent a force under Diwan Nanun Mal, Sirdar Hamir Singh of Nabha with the Bhais of Kythal assembled for its defence, and compelled the Khan to raise the siege and give them battle, in which he was defeated and killed. Trophies of this victory are still preserved at Jhind, and the tomb of the Khan is to be seen within the principal gate.

The conquest to the south:

After this, Gajpat Singh, accompanied by the Pattiala detachment, made an expedition against Lalpur in Rohtak, and obtained, as his share of the conquered country, the district of Kohana. But Zalita Khan, the son of the Rohilla Chief Najib-ud-dowlah, (Najib Khan), marched with Ghulam Kadir against the allied Chiefs with so strong a force that they saw it was hopeless to resist, and, at an interview at Jhind, the Raja was compelled to

Gold 24 Rs. Per 100 coins

State.... 17 Rs 2-1/2 anas

Establishment dues,.... 1 Rs 2 anas

Miscellaneous expenses, 5 Rs 11-1/2 anas

VI. The currency is principally confined to the area of the State, but there are a good many Pattiala rupees about in the neighbouring districts, but not probably beyond the limits of the civil Division.

I. Political conditions etc.- The Jhind Mint would seem to have been established at the same time as that of Pattiala, as the inscription is exactly the same. There does not appear to have been any correspondence with this Agency or the British Government regarding its continuance or conditions.

II. Nature, title, and character of the coinage, The rupee is called the " Jhindia ; " it is 11-1/4 mashas in weight.

The inscription is, as in the case of the Patiala Rajah Shai rupee,

- "Hukm shud az Qadir-i-bechun ba Ahmad Badshah

- Sikha zan bar sim-o-zar az ouj-i-mahi ta ba Mah"

The the third sentence which appears on the Pattiala coin is omitted in the Jhind inscription.

Translation of the inscription has been given above.

III. The out-turn is quite uncertain; on the occasion of marriages large sums are coined, but otherwise only the actual quantity considered

give up A portion of Kohana, though he was allowed to retain certain villages known as Panjgiran, and Pattiala had also to abandon a great part of its conquests in Hisar, Rohtak and Karnal.*

The relation of Raja with Pattiala:

Raja Gajpat Singh Was a constant ally of the the Pattiala Chief and accompanied him on many of his expeditions. He Joined in the attack on Sirdar Hari Singh of Sialba ; aided in subduing Prince Himmat Singh, who had risen in revolt against his brother Raja Amar Singh; and, in 1780, marched with a force composed of Pattiala and Jhind troops to Meerat, were the Sikhs were defeated by Mirza Shafi Beg, Gajpat Singh being taken prisoner, and only released on payment of a heavy ransom.

necessary is struck. The value of the coin is said to be about 12 annas, but I have been unable to procure a specimen in Ambala, and the shrafs in our markets know little about this coin.

IV. Process of manufacture, etc— The only point noted is, that the die is entrusted to the care of the State Treasurer, the process of manufacture and arrangements of the workshops, &c, is not noticed.

V. The arrangements for the receipt of bullion, — Bullion has never been tendered for coining at the Jhind Mint, so no rates for conversion have been fixed.

VI. The general area of currency- Only Within the State of Nabha.

I. Political conditions etc— This Mint appears to have been established under Sikh rule ; there has never been any correspondence on the subject with the British Government.

II- Nature, title, and character of the coinage. — The rupee is called the “Nabha” rupee; its full weight is 11-1/4 mashas, of which 10 mashas 4-1/4 ruttees is pure silver. It is thus 5 ruttees in actual weight, and 2-1/2 ruttees in pure silver less than the British Government rupee.

Gold Mohurs are occasionally struck by the Nabha Government for its own use. The weight of the Mohor is 9-3/4 mashas, and it is of pure gold.

The description on both coins is the same, viz :—

- "Deg, teg-0-fatah nasrat be dirang;

- Yaft az Nanak Guru Govind Singh.

- Julus meimunat manue Sirkar Nabha, samhai 1911."

The above may be rendered :—

- "Food, sword, and victory, were promptly obtained from Nanak by Gurd Govind Sing."

* Vide ante p. 44.

When Sahib Singh succeeded his father at Pattiala, Raja Gajpat Singh did his best to restore order, and assisted Diwan Nanun Mal to put down the rebellion of Sirdar Mahan Singh who had proclaimed himself independent at Bhawanigarh. He also in person marched against Ala Singh of Talwandi, who had thrown off the authority of Pattiala.

Death of Raja Gajpat Singh and his eldest son, Mehar Singh, with the extinction of this branch of family:

In 1786, while engaged in an expedition against refractory villages in the neighbourhood of Ambala, with Diwan Nanun Mal and Bibi Rajindar, sister of the Raja of Pattiala, he fell ill with fever and was carried to Sufidon, where he died, aged fifty-one. His eldest son, Mehr Singh, died in A. D. 1780, leaving, one son, Hari Singh, who was put in possession of Safidon by Raja Gajpat Singh.

In the above, food is expressed in the couplet by the word deg, signifying the large cooking-pan in use among the Sikhs; but I have found it very difficult to introduce pot or pan into the English rendering ; the spirit of the expression is “abundance, “

III. The out-turn of the establishment, value, etc. The Nabha officials have not noticed the out-turn, but I know that as in the other States, money is only coined on grand occasions, or where there is supposed to be need of it ; so that no rule can be fixed.

The value is exactly 15 annas.

IV. The Mint establishment consists of one Superintendent, one Tester, one Smelter, a silver-smith, and a black-smith.

The silver is carefully refined in presence of the Superintendent, who sees the metal brought up to the proper standard.

V. Silver has often been received from without for coining. Gold has never been tendered.

The mint duty for coining is 14 annas per hundred rupees, which is distributed as follows :—

- To Silversmith....4-3/4 annas percent

- Smelter....2 annas percent

- Blacksmith....1/4 annas percent

- Tester....1 annas percent

- Superintendent....3/4 annas percent

- State dues....5-1/4 annas percent

- Total=14

VI. General area of the currency. — These rupees find their way into the neighbouring markets, but not to any great extent

But he was of dissipated habits, and in a state of intoxication fell from the roof of his house and was killed. This was in 1791, when he was only eighteen years of age. He left a daughter, Chand Kour, who was married to Fatah Singh, the son of Sirdar Bhanga Singh, the powerful Chief of Thanesar. After her husband's death, she, with his mother Mai Jiah, and another widow, Rattan Kour, succeeded to the estate which fell entirely into her possession in 1844, and was held by her in independent right till her death in 1850, when it lapsed to the British Government. The widow of Hari Singh, Dya Kour, retained, till her death, the district of Khanna, which had been given to her by her father-in-law, when it also lapsed.

The fort of Jhind built:

The town of Jhind was much enlarged by Raja Gajpat Singh, who built a large brick fort on its northern side, but at no time was it a place of much strength.

Raja Bhag Singh

The possessions of Gajpat Singh were divided between his sons, Bhag Singh and Bhup Singh, the latter taking the estate of Badrukhan, and the elder, Jhind and Sufidon, with the title of Raja.

His expeditions and wars:

Bhag Singh was twenty-one years old when he became Chief. Much of his history has been given in the history of Pattiala, with which he was generally allied.

In 1786, the districts of Gohana and Khar Khodah, were conferred upon him in jagir by the Emperor Shah Alam, and, in 1794, he joined the Pattiala army under Rani Sahib Kour in the attack on the Mahratta Generals, Anta Rao or Amba Bao, and Lachman Rao, at Rajgarh near Ambala, when a night

Attack was made on the enemy's camp with great success. In the next year the Raja lost Karnal, which was captured by the Mahrattas and made over to George Thomas, who had been of good service in beating back the Sikhs who had crossed the Jamna in force and threatened Saharanpur.

The wars and conquests of Thomas have been related in the history of Pattiala, and the expeditions which he undertook against Jhind and Sufidon in 1798 and 1799.* Supported by kinsmen and neighbours, Raja Bhag Singh was fortunate enough to repulse his enemy, and in 1801, he went to Dehli in company with other Chiefs to ask General Perron, Commanding the Northern Divisions of the Mahratta army, for assistance to crush the the adventurer whose resistance at Hansi, on the southern border of the Jhind State, was perpetual menace to all the Sikh Chiefs in the neighbourhood.

Thomas expelled from the Punjab:

The expedition against Thomas in which Raja Bhag Singh personally joined was successful, and he was driven from Hansi and compelled to seek an asylum in British territory.

Raja Bhag Singh makes friends with the British and joins General Lake, AD 1803:

Raja Bhag Singh was the first of all the great Cis-Satlej Chiefs to seek an alliance with the British Government. Immediately after the battle of Dehli, on the 11th September 1803, he made advances to the British General, which were favorably received; he then joined the English camp and his title to the estate of Gohana and Khar Khodah, in the neighbourhood of Dehli, was upheld by General Lake, who writes of Bhag Singh as

* Ante pp. 81—88.

a friend and ally.* Bhai Lal Singh of Kythal, who had great influence with the Jhind Raja, induced him to declare thus early for the English. He was a remarkably acute man, and saw clearly which would eventually prove the winning side ; on this side be determined to be himself, and induced his friend to be equally wise. After having made their submission, they returned to their respective territories, but in January 1805, after the defeat of the hostile Sikhs by Colonel Burn, they thought that active service would prove more advantageous to their interests, and joined the British army with a large detachment. For several months the Raja remained with the General. His services were not important, but his influence had a good effect, and on one occasion, he, with Bhai Lal Singh, held Saharanpur while Colonel Ochterlony was in pursuit of the Mahratta.†

At length the Sikh Chiefs were tired of a fruitless struggle, and accepting a general amnesty, peace was restored on the North West Frontier.

Raja Bhag Singh joined Lord Lake in his Pursuit of Jaswant Rai Holkar in 1805, accompanying him as far as the Bias, whence he was deputed to Lahore as an envoy to his nephew, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, to warn him of the approach of the English General and against espousing the hopeless cause of Holkar, who was then in the last

* A Sanad from Lord Lake, dated the 26tb September 1808, informing the officers of the Shahajahanabad Suba or Division that paragana Kharkhauda Sonipat has been confirmed to Raja Bhag Singh.

A Sanad from Lord Lake, dated 7th March 1804, informing the officers of the Shahjahanabad Suba, that Parganahs Gohana, Faridpur, and Barsat, have been allowed to Bhai Lal Singh and Raja Bhag Singh.

† Colonel Burn to Colonel Ochterlony, dated 7th, 13th, and 24th, February, and 8th, 18th, and 27th March 1805.

extremities. An agent of Bhai Lal Singh accompanied him, and the mission was conducted entirely to the General's satisfaction. It is probable that Bhag Singh was able to exert considerable influence with his nephew in favor of the English, and at any rate the negotiations, which had been commenced, were broken off, and Holkar was compelled to leave the Punjab.

The grants made to him in reward for service:

Raja Bhag Singh returned with Lord Lake to Dehli, and received the grant of the pargannah of Bawanah immediately to the south-west of Panipat, as a reward for his services : it was a life grant in the name of Kour Partab Singh. Hansi had first been given him, but at his own request this district was exchanged for Bawanah. The villages of Mamrezpur and Nihana Kalan were also granted him in Jagir.*

The disputes between Pattiala, Nabha and Jhind, and the struggle for supremacy at the Pattiala Court between the parties of the Raja and his wife, ending in the mediation of Maharaja Ranjit Singh have been described in the history of Pattiala. † Raja Bhag Singh gained in territory by his nephew's visit; and during the expedition of 1806 he received from the Maharaja the following estates: — Ludhiana, consisting of 24 villages, worth Rs.

* A Sanad from Lord Lake, dated 15th March 1806, allowing Parganah Bawanah to Kour Partab Singh, son of Raja Bhag Sngh, on a life tenure.

A sanad from Lord Lake, dated 19th March 1806, allowing the village of Mamrezpar to Raja Bhag Singh, in jagir on a life tenure.

A sanad from Lord Lake at 20th March 1806, informing the officers of Parganah Khar Khodah that the village of Nihana Kalan formerly enjoyed by Raja Bhag Singh, on payment of Rs. 1200 is granted to him in Jagir for life.

† ante pp 92—104.

15,380 a year ; 24 villages of Jhandiala, from the same family, worth Rs. 4370 ; two villages of Kot, and two of Jagraon, worth Rs. 2,000 a year ; all taken from the Rani of Rai Alyas of the Mahammadan Rajput family of Raikot ; while from the widow of Miah Ghos he acquired two villages of the Basia District. During the expedition of the following year, the Maharaja gave him three villages of Ghumgrana, conquered from Gujar Singh of Raipur, and 27 villages of Morinda in Sirhind, conquered from the son of Dharam Singh, and all together worth Rs. 19,255, a year. *

Survey of the Jhind territory:

in April 1807, Raja Bhag Singh readily consented to the survey of his country by Lieutenant F. White, and did all he could to make the expedition successful,† A Survey in Sikh territory was not then so common-place a proceeding as at present, for the people were both ignorant and suspicious and generally imagined that a survey of their country was only a preliminary to its annexation, and two years later, in Pattiala, Lieutenant White's party was attacked and nearly destroy. †† But Raja Bhag Singh was not altogether superior to the prejudices of his country-men. He was well disposed to the English and a faithful ally, but he had not entire confidence in his new friends, and it was through his advice that Maharaja Ranjit Singh did not trust himself

* statement of the conquest of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1806, 1807 and 1808, prepared by Sir D. Ochterlony, vide Appendix A. Archibald Seaton, Resident Dehli, Circular of 1st November 1806. Gosha-i-Punjab, p. 571. Archibald Seton to Genral Dickens, 20th August 1807.

† Resident at Dehli to Lieutenant White, 26th, 28th, of April, 25th of May 1807.

†† Captain White to Resident Dehli, 24th and 25th December 1809. Vide ante p. 133.

in British territory. This Chief, in the spring of 1808, much wished to visit the sacred fair of Hurdwar, on the Ganges. He sent Sirdar Mohr Singh Lamba and Sirdar Bishan Singh to Dehli to obtain the permission of the Resident, and, at Hurdwar, all arrangements for his reception, including an escort of three thousand follower, were made. But, at the last moment, Raja Bhag Singh dissuaded him from the idea. He declared that the Envoys, Mohr Singh and Bishan Singh, were playing him false ; that they were converting all their wealth into notes and Government paper at Dehli, intending to leave the Punjab for Benares ; that their declarations of the security with which the Maharaja would make the journey were untrustworthy, and that he could not travel with any safety unless accompanied by his whole army. The design of visiting Hurdwar was consequently abandoned. There is no knowing on what grounds Bhag Singh considered the Maharaja's servants untrustworthy, but there was probably some season for his belief, since Sirdar Mohr Singh left the Punjab for Benares a year or two later, contrary to the wish and orders of his master.*

The Hardwar fair:

Raja Bhag Singh himself visited Hurdwar, and, after the fair† went to Lahore, where he remained in attendance

* Letter of Maharaja Ranjit Singh to Resident Dehli of 6th August 1808. Resident Dehli to Magistrate Saharanpur, 18th and 32nd March. Circular of Resident 20th March 1808. To C. Metcalfe Esquire, 32nd March, and 2nd April 1808. Gosha-i-Punjab, p. 580. Punjab Chiefs, p. 544.

† Mr. Metcalfe to Resident Dehli 10th April 1808. An extract from this letter may not be without interest, as this was the first large festival at Hurdwar under the management of the British, and the description is not unlike that given of the Great Fair held sixty years later in March 1867.

on Ranjit Singh, and accompanied him in the Cis-Satlej campaign of 1808, undertaken while Mr. Metcalfe, the British Envoy, was with the Sikh camp.*

The Siege of Ghumgrana:

At the beginning of 1808, Raja Bhag Singh with Bhai Lal Singh, the Nabha Raja and a Pattiala contingent, attacked the strong fort of Ghumgrana, owned by Gujar Singh, son of the famous Tara Singh Gheba, who had lately died. The siege proceeded for some time, till Ranjit Singh raised it by a message ordering the besiegers to desist. The Maharaja did not take this course in the interests of the owner, but sent a force of his own against the fort, took it without resistance, and gave it to one of his favorites,

Raja Rajgan Sahib Singh of Patila, Raja Bhag Singh, Sandar Bhai Lal Singh, and Sirdar Gardit Singh, were the principal Sikh Chieftains that came to the Mela; and though not charged with any prescribed duty with respect to these, I thought that the nature of my situation called on me to pay them every suitable attention, with particular reference to the distinguished rank of Raja Rajgan Sahib Singh. All the Sikhs who attended the mela in great numbers, behaved with perfect propriety, and the Chiefs did not express any objection to the application to their own followers of the general prohibition against carrying arms into the place when the mela was held.

“Amongst the innumerable crowds that were assembled at Hardwar there did not take place the slightest disturbance, and the perfect good order that was preserved had a surprising effect upon the multitude. It is not within the line of my duty to dwell on this subject, but I cannot refrain from remarking that the conduct of the vast numbers that came from all quarters was most gratifying to the feelings of an Englishman. Their prayers for the prosperity of the British Government were most fervent ; the respect shown to an Englishman whenever he appeared struck us all as far exceeding anything that we had met with before; their expressions of admiration at the whole arrangement of the mela were unbounded, and they repaid the care bestowed for their comfort with an evidently heartfelt gratitude. I am afraid to attempt to describe what at the place manifest to all, lest yon should suspect that the gratification excited by the universal joy might be carrying me into fields of romance, but I am satisfied that the loud praises and thanks giving of the honest multitude proceeded from the sincere effusions of their hearts; and I am confident that the reports, which they will carry to their distant homes, will considerable extent the fame and reputation of the British Government.”

* C. Metcalfe Esq., to Resident at Dehli, October 1st 1808.

Karam Singh of Nagla. Raja Bhag Singh still retained some of the villages which he had seized in its neighbourhood, and though Karam Singh represented to the Maharaja that they were necessary to the completeness of his jagir, yet the latter did not like to compel his uncle to restore villages, to which, when all were robbers, he had as good a right as any one else. A bitter feud between Raja Bhag Singh and Sirdar Karam Singh was the consequence, and perpetual fighting and bloodshed between the rivals took place around Ghumgrana. The British Envoy had himself an opportunity of observing the state of affairs, for, on one occasion, when he was taking his evening ride in the vicinity of the fort, he was fired upon from one of Bhag Singh's villages, whose defenders believed his escort to be their enemies.*

The ransom of Maler Kotla:

Raja Bhag Singh was one of the Chiefs who were securities for the ransom of Maler Kotla, from which, in October 1808, Ranjit Singh demanded the tribute of a lakh of rupees. Only Rs. 27,000 were at once forthcoming, and for the balance, Pattiala, Nabha, Jhind and Kythal, became security, receiving from Maler Kotla, Jamalpura and other territory in pledge. By the treaty of Lahore the conquests of Ranjit Singh during his last campaign to the south of the Satlej had to be restored, and Jhind, with the other Chiefs, was compelled to resign the lands given by Maler Kotla, and the Maharaja, after some negotiation, absolved them from the necessity of paying the sum for which they had become sureties. †

* Envoy to Labore to Secretary to Government 20th November 1808.

† Mr. C. Metcalfe to Government of India 26th October 1808, and Resident Dehli to Government, lOth Angust and 16th August 1809.

The feelings of Raja Bhag Singh towards the chief of Lahore and his intrigues:

Raja Bhag Singh's confidence in the moderation of his nephew was very much shaken by the unprovoked attack on Maler Kotla, and he perceived that his own possessions would be safe only so long as they were not coveted by his dangerous relation. He accordingly turned to his friends the English with whom he had maintained the most amicable relations, prompted by his adviser Bhai Lal Singh. The Resident at Dehli had addressed, on the 21st November, a letter to the Raja, informing him that although the British Government was not prepared actively to interfere, yet that the Governor General had written to Maharaja Ranjit Singh, and expressed a hope that the Cis-Satlej Chiefs, the friends and allies of the English, would be left unmolested by him. In reply, the Raja declared his unalterable feelings of friendship for the British Government, and his confidence that, under its protection, his power and honor would be secure. The Resident again wrote in general terms, for the idea of a protectorate of the Cis-Satlej States was not yet matured, that the Government had no wish save the perpetuity of the rule of the Sikh Chiefs, and had full confidence in their assurances of good- will.*

The Raja continued to address the Resident and solicit his good offices in his favor, and a translation of a portion of one of his letters will show the mistrust which the Chiefs had began to entertain of Ranjit Singh.

His letter to the Resident to Delhi:

"I have lately received two letters from you, containing assurances of kindness and calculated to

* Letter of Raja Bhag Singh to Resident of 3rd December, and reply of Resident, 4th December 1808.

"tranquillize my mind The perusal of these letters has inspired me with confidence, and filled me with gratitude : may the Almighty reward you.

“The state of matters in this quarter is as follows : — Previously to the receipt of your letters, Raja Sahib Singh had, with a view to his own safety, made an arrangement for meeting Maharaja Ranjit Singh, and he accordingly proceeded, by successive marches, to the camp of the Maharaja, and a meeting took place. In conformity to the custom of interchanging turbans, which is established among Sikh Chiefs, the Maharaja and Raja Sahib Singh, exchauged theirs, and seemingly settled everything. But in truth, we four Sardars* are inwardly the same as ever, and adhere to the same sentiments to-wards the British Government which we left and expressed on the first day of our being dependant upon it, and which all repeated to you when we visited you, and explained the particulars of our situation. This will doubtless he present to your recollection. Under every circumstance, we trust that it is the intention of the British Government to secure and protect us four Sardars. As Sardar Ranjit Singh is now preparing to cross the Satlej, it is probable that he will soon cross that river. Raja Sahib Singh will take leave at Laknow and return to Pattiala, and Bhai Lal Singh and myself, after accompanying Ranjit Singh to the other side of the Satlej, will return to Pattiala, and after consulting together with respect to everything, we will communicate the whole of the result to your, in detail "

Bhag Singh visits Mr. Seton, the resident:

The next month, Maharaja Ranjit Singh having returned to Lahore, Raja Bhag Singh set out for Dehli to have an interview with Mr. Seton, the Resident. He reached Karnal, and from thence he wrote announcing his arrival and requesting permission to proceed. But, at this time, General Ochterlony was advancing with a strong force to the Satlej, to strengthen, by his propinquity, the arguments of Mr. Metcalfe, the Envoy at Lahore, whose tedious negotiations seemed still far from any satisfactory conclusion, and the Resident, thinking Bhag Singh's presence with the English force would have a good effect, advised him to join it, which he at once did with his troops, overtaking the General at Buria.*

The reason which induced this action on the Bhag Singh, was that he had heard that an agent of the Lahore Maharaja was on his way to Pattiala, to summon him, Jaswant Singh of Nabha, and Cheyn Singh, the confidential agent of the Pattiaja Chief, to Lahore. To a journey to Lahore Bhag Singh had at this time a strong and natural objection. He was an independent Chief and at liberty to make such friends as pleased him ; but his conscience told him that his conduct to Ranjit Singh, who had always treated him with the greatest consideration and had much enlarged his territories, was somewhat questionable, and he had no wish, at present, to meet him. The Lahore agent, accordingly, on his arrival to Pattiala, found Bhag Singh absent, and this was an excuse for

* Letters from Raja Bhag Singh to Resident Dehli, 13th and 25th January 1809.

Resident to Raja Bhag Singh, 15th Jannary, and to Government of India, 15th January 1809.

Maharaja Sahib Singh to decline to send his own agent, an excuse of which he was ready enough to avail himself.*

He joins General Ochterlony

Raja Bhag Singh was received by General Ochterlony with great kindness, and the information which he was able to give with regard to the disposition of the several Sikh Chiefs was of much value. All of them were, according to the Raja, disposed to welcome the English and joyfully accept their protection, though one or two, like Sirdar Jodh Singh of Kalsia, were under too heavy obligations to Ranjit Singh to come forward at once and declare against him. It was explained to the Raja that the restitution of conquests during the late campaign must in justice be enforced against the friends of the British as against the Maharaja; with which the Raja fully agreed, the more readily that he would by this act of justice lose no more than territory worth Rs. 4,000 a year, which had been taken from Rani Dya Kour and conferred upon him.†

And marches with him to Ludhiana:

The Raja continued with General Ochterlony till his arrival at Ludhiana, at which place the detachment was ordered to halt, and acted as a mutual friend in the negotiations which were necessary between the General and the Lahore agent On the 10th of February, at Ghumgrana, he received a confidential message from the General, stating that the following

* Resident to Government of India, dated 18th and 19th January 1809. Vide ante p. 24

† Resident Dehli to Government dated 25th January. Raja Bhag Singh to Resident dated 25th January. Government of India to Resident dated 13th and 27th February 1809. Sir D. Ochterlony to Government of India, dated 20th January 1809.

He assists in the negotiations:

Day he would have to march to Ludhiana, which the Lahore troops, in spite of the Maharaja's promises, had not yet evacuated, and asked him, as a friend of both parties, to take such measures as he judged best to prevent the occurrence of hostilities, which would be the result, should the Sikhs not cross the river without delay. The Raja urged the General to halt, but this he at first refused, as he had received direct orders to advance, and expressed his belief that Sirdar Gainda Singh, in command at Ludhiana, would evacuate the fort at his approach, in accordance with the promises of the Maharaja. The Lahore agents who were in camp, denied that their master had ever made any promise of the kind, and the assertion, though evidently made only to delay the advance, so staggered the General, that he consented to march to Sirnawal instead of Ludhiana, and there await further orders from General St. Leger, then Commanding the army in the field.* The conduct of General Ochterlony was severely censured by Government in attending to the Lahore agents rather than to their direct orders, but in the advice given by Raja Bhag Singh there was nothing of treachery, and only a weak desire to maintain such friendship as was possible with both sides.

The arrival at Ludhiana, AD 1806:

The detachment arrived at Ludhiana on the 19th of February. This town, well situated on the river Satlej and commanding the principal northern road, had been for only two years in possession of Raja Bhag Singh,

* Colonel Ochterlony to General St. Leger, dated 10th February 1809. Government to Colonel Ochterlony, dated 30th January and 30th March 1809. Colonel Ochterlony to Government dated 14th February 1809, and to Resident Dehli dated 27th January 1809.

and was one of the advantages he had gained from his connection with Ranjit Singh. He was not, however, unwilling to give it up to the English who desired to form there a permanent cantonment, hoping to obtain in exchange the pargannah of Karnal, which had once been in his family. He addressed the Government to this effect, stating that he would not be able to collect the revenues of the forty-one villages round Ludhiana, having lost possession of the fort, and praying that these should be taken by Government, giving him in exchange the pargannah of Karnal, with the right to collect the duties, or, if this were impossible, the pargannah of Panipat. If the revenue of the latter should exceed that of Ludhiana, which was Rs. 17,800, he offered the pargannah of Jhandiala in lieu of the excess. *

General Ochterlony supports his application:

General Ochterlony, who had evidently a strong liking for the Raja, strongly supported his application, writing to the following effect : —

“It would be unjust in me were I to withhold on this occasion an expression of the earnest desire I feel to effect the wishes of the Raja, not merely from a conviction that the loss of the fort will occasion a considerable decrease, if not entire loss of the collections of the Taluqa Ludhiana, but because he has in this, and every other instance, acted with an openness and candour which reflects an honor on his character, showing himself grateful for the benefits derived from the British Government Without affecting to disguise a very warm interest in the fate of his nephew Raja Ranjit Singh, at the same

* Letter of Raja Bhag Singh to the Resident Dehli, 25th February 1809.

" time manifesting a readiness to comply with every request which could be considered of importance, beyond even my most sanguine expectations, — as I certainly was prepared for a little hesitation if not a request for a short delay when I informed him that His Excellency the Commander-in-Chief had directed the interior of the fort to be immediately cleared and levelled ; — and it was most satisfactory to me to observe that without hinting at the request he had before personally urged, he gave an immediate and cheerful acquiescence, observing only that he had experienced too much of British liberality to fear any ultimate loss." *

The reasons in favour of the exchange:

The Karnal pargannah, which was in a very turbulent condition, and which rerequired strong measures to kept its inhabitants in order, had already been conferred on Muhammad Khan, a Patan of the Mandil tribe. The Government acknowledged the services of Bhag Singh, and would have been glad to restore, by an act of justice, the district of Ludhiana to the family of Rai Alyas ; but considered that there was no obligation to reinstate the latter at the hazard of other political interests. Compensation for the absolute loss sustained by Bhag Singh in the cantonment of British troops at Ludhiana was all that was necessary, for he, commendable as his conduct had been, had sacrificed no interest for which he would not receive an equivalent, while, in common with other Sikh Chiefs, he had derived the solicited benefit of British protection.

* General Ochterlony to Resident, 25 February 1809.

An obligation to restore Ludhiana to its former Muhammadan owners could be only maintained With great danger and imprudence.

" To pursue the dictates of abstract justice and benevolence wrote the Governor General by the indiscriminate redress of grievances beyond, the admitted limits of our authority and control, would be to adopt a system of conduct of which the political inconvenience and embarrassment would not be compensated by the credit which might attend it."

The Government consequently declined to entertain the Karnal proposal, but allowed Raja Bhag Singh fair compensation, although it was observed that this was the less necessary, as the occupation of the military post of Ludhiana was only intended to be temporary, and that consequently the fort and the ground at present occupied by the British detachment would revert to “that Chief." * The Military station of Ludhiana has, nevertheless, been retained from that day to this,†

* Resident at Dehli to Government, 24th February and 3rd of March. Government of India to Colonel Ochterlony, 3rd April 1809, and to Resident of Dehli of the same date. Resident Dehli to Colonel Ochterlony, 24th February, 4th and 10th March, and let April 1809.

† Lndhiana is a town of small intrinsic value as a military poet, and, in 1868, only 800 Native troops were stationed there, with sixty British artillery men in the fort of Philor on the opposite bank of the Satlej. When the English first occupied Ludhiana, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who seemed to know better than the Government that the occupation would not be temporary, directed his General, Diwan Mokham Chand, to build the fort of Philor on the opposite bank on the site of an Imperial Serai.

That the Government had no intention of retaining Lndhiana as a Military Station when it was first occupied, is evident from the despatch above quoted, and also from former despatches of the 18th of March 1809, from the Governor General in Council to Colonel Ochterlony and Lieutenant General Hewett, the Commander-in-Chief. The right to advance to the Satlej at any time could not, however, be surrendered, and this

A second attempt of Raja to obtain Karnal:

Raja Bhag Singh was not at all pleased with the refusal of the Government to allow him Karnal, which, as an old possession of his father's, he much desired to regain, and the next year made another attempt to possess himself of the coveted territory.

The Estate of Dharampur:

Bhara Singh, the jagirdar of Dharampur, or in Karnal, a valuable estate worth Rs. 12,000 a year, died early in 1810, and the Raja at once claimed to resume the property. He pleaded that the whole pargannah had belonged to his father, Gajpat Singh, and that the estate in question had continued in the family, though in the name of Bhara Singh, one of its dependants ; and in support of the claim he produced a petition from Bhara Singh to Lord Lake, to the effect that the petitioner had long entertained 50 horse for the service of the rulers of Dehli, in consideration of which he had held in jaidad, Moranah and four other villages in Karnal, and had, moreover.

was one of the reasons that Ranjit Singh was not pressed to relinquish the Cis-Satlej conquests of 1806, 1807.

Ludhiana remained a Political Agency till the close of the first Sikh war, generally in charge of an Assistant Agent. Sir David Ochterlony and Sir C. Wade being the only officers with the full powers of Agents.

- 1808 to 1815, Sir David Ochterlony.

- 1815 „ 1816, Captain Brown.

- 1816 „ 1823, Captain W. Murray.

- 1823 „ 1838, Sir C. Wade.

- 1838 „ 1839, Captain E. Robinson.

- 1839 „ 1840, Lieutenant J. D. Cunningham.

- 1840 „ 1841, Mr. H. Vansittart.

- 1841 „ 1842, Mr. P. Melvill.

- 1842, Captain C. Mills.

- 1842 to 1843, Mr. H. Greathed.

- 1843 „ 1844, Captain C. Mills.

- 1844, do. & Abbott.

- 1844 to 1845, do. C. Mills.

- 1845 „ 1846, do. E. Lake.

enjoyed a pension of Rs. 189, per mensem for the confirmation of which he solicited a Sanad.

The order of Lord Lake:

This petition was endorsed by Lord Lake as follows : —

- “On consideration of service and fidelity, the arrangement which prevailed in time of M. Perron, is hereby continued.”

Now it is evident that Lord Lake could not have bound himself to more than He was cognizant of; and his endorsement could thus be only considered as granting that which was solicited on the face of the petition, Viz., the continuance to Bhara Singh of the possession of the estate in question so long as he should furnish the 50 horsemen ; find, indeed, jaidad grant is scarcely capable of any other construction. Besides, Raja Bhag Singh, by subsequent admissions, destroyed his own case. It may have been quite true that Dharampur was held by him after the loss of the rest of Karnal, but he also stated that it has been twice wrested from him by the Mahrattas, find that, after this second occupation, it was restored by George Thomas at the time that he received Karnal in jaidad. Now it is notorious that Thomas received Karnal in 1795, both as a reward for his successful opposition to the Sikhs at Saharanpur and to enable him to maintain a force to act against them in conjunction into the Mahrattas. It is impossible that he should have allowed Raja Bhag Singh to retain the villages, unless he was an ally of the Mahrattas, and he was on the contrary, in opposition to them. But even dmitting that these villages did not revert to the Mahrattas, yet their right to dispose of them was admitted by

Bhag Singh himself, since he did not deny the grant under which Bhara Singh held them, but, on the contrary, identified, by date and description, his own grant with that of Sindhia of the 23rd of April 1800, about which time Bhag Singh asserted that he bestowed the villages on Bhara Singh, when George Thomas invested Jhind in 1799. The service of the body of horse, moreover, as specified in the grant, was not due to Bhag Singh, but to the Mahrattas, and the pension was paid by them.

The claims of Raja rejected:

The Government were satisfied that the Raja possessed no title whatever to the estate, and seeing no reason for alienating it in his favour, directed it to be resumed.*

The attitude of Raja of Pattiala:

During all the troubles which came on the Pattiala family t in the imbecility of the Maljaraja, the Regency, and the intrigues and quarrels among the young Prince ; Raja Bhag Singh showed himself the best friend of the house. He was not a man of ability or force of character sufficient to restore order and save the State from the worst evils of misgovernment and anarchy ; but what he could do he did, and was almost the only disinterested adviser Pattiala could consult.††

His excesses and their result

But his health was now fast breaking. Like most of the Sikhs Chiefs he was a man of dissipated habits and a hard drinker. Finding that his excesses endangered his

* Resident Delhi to Mr. Fraser 28th June. Mr. Fraser to Resident 8th March and 17th April 1810. Resident to Government 32nd Aagut and 10th September. Government to Resident 18th October 1811,

† Vide pp. 135—138.

†† General Ochterlony to Government of India 12th July 1811, 3rd April 1813.

life, he was induced to give up drinking for a short time, but the habit was too confirmed to be abandoned, and the result of resuming it was a paralytic stroke, in March 1813, which deprived him of speech and almost of the power of motion. There was no doubt that his illness would have a fatal termination, and it became necessary to think of his successor.*

The draft will by which the elder son was dispossessed

About a year before, when the Political Agent was at Pattiala, the Raja had given Draft Will, containing the arrangements which he desired to take effect at his death. By this he left to his younger son, Partab Singh, the Fort and district of Jhind, and declared him his successor, leaving to the elder son, Fatah Singh, only the districts of Sangrur and Basia, with a request to the British Government that he might continue to hold the jagirs he enjoyed from them for life. When the Raja made this will he was in sound health, both of body and mind, and it was the expression of his deliberate intention and wishes. He had no particular cause of complaint against Prince Fatah Singh, but the younger son was his favourite, the child of a woman to whom he had been much attached and who had long been dead.

The Agent tried to induce the Raja to change his determination. He pointed out that certain ill-feeling and disputes must be the result between the brothers, and that the State would suffer thereby, while the British Government was strongly in favour of the rule of promogeniture ; but the

* Sir D. Ochterlony to Government, 20th April 1813.

Raja’s arguments in its favour:

Raja had set his heart on the arrangement. He urged that the father had the right of nominating his own successor and bequeathing his lands as he pleased. That he was, himself, a second son, and had been preferred by his father, and that the custom of the Jhind family was not in opposition to the disposition he had made. The contents of the will, which the Raja then made over to Sir David Ochterlony, he desired to be kept secret, and it was only after his paralytic attack that the Agent forwarded it to the Resident at Dehli for transmission to the Government of India.* The secret had now become known, and Prince Fatah Singh with Jaishi Ram and Shadi Ram, the very men who had been privy to the will, were now intriguing to set it aside, for Partab Singh was universally disliked, and very few, save his immediate followers and favourites, regarded his succession without apprehension.

The refusal of the Government to sanction the proposed arrangement:

The Governor General was unwilling to sanction the Raja's will, considering that there was no proved custom in the Jhind family of an elder son being superseded by a younger.

The despatch of the Governor General:

" Whatever doubt the Governor General might entertain the despatched continued with respect to the justice or propriety of Opposing the will of Bhag Singh, if there were good reasons to suppose that it was warranted by the laws and usages of his tribe and family, His Lordship in Council can have no hesitation, under the contrary impression which exists

* General Ochterlony to Government 2lst April 1813.

"in his mind, in refusing to afford the countenance of the British Government to an arrangement which is, in this Lordship's estimation, no less unjust in its principle than likely to be pernicious in its effects. You are authorized therefore to declare to the parties concerned, and to the surviving friends of the family, after the death of Bhag Singh, that the succession of Kour Partab Singh cannot be recognized by the British Government. You are authorized, moreover, to employ the influence of the name and authority of Government in support of the claims of the elder son to the Raj, and to the possessions generally of Bhag Singh, or rather to that superior portion of them, which, by the terms of the Will, has, together with the Raj, been bequeathed to the second son, signifying at the same time, that care will be taken to secure to Partab Singh a suitable provision, as well as to see the bequest to the younger son duly carried into effect. Your own judgment and local knowledge will suggest to you the most proper means of rendering the influence of Government most effectual in sustaining the rights of the eldest son, without invoking the necessity of its authoritative interposition, which the Governor General in Council will be desirous of avoiding, and which ought on no account to be resorted to without the express sanction of Government ; and it will no doubt occur to you that the aid and cooperation of Bhai Lal Singh and other friends of the family, will be profitably employed for the purpose. It may be expected that their discernment will perceive the many advantages attending a fixed and definite rule of accession, and, unless they are misled by

" some personal interest of their own, that they will be disposed to support the retentions of the elder son of Bhag Singh, in preference to up holding the provisions of a will Which appears to have been dictated Only by the caprice or Injustice of the testator. It is superfluous to observe that in communicating on this subject with Bhai Lal Singh and others, it will be proper carefully to avoid anything that can be construed into an admission of their right to interfere in the regulation of the succession or management of the affairs of the family. A just and Simple arrangement would be, either to reverse the provisions of the will in favor of the eldest and second son, or to assign to the latter other lands equal in value to those designated in the will as the provision of the elders" *

The grants made by the British Government to the Raja:

Regarding the Jagirs granted by the British Government to the Raja, and which he desired to be confirmed to his elder son during his life, the Governor General reserved his opinion.

These grants were four in number : first was Gohana and Faridpur, situated to the south west of Barwanah, and granted, in 1804, to Raja Bhag Singh and Bhai Lal Singh jointly, in recognition of their services against the Mahrattas.

Barwanah was granted to Bhag Singh in 1806, in the name of his son Partab Singh ; Kharkhoda and Mumrezpur in the Hansi purgannah were granted him in Jagir in March 1806, having formerly been held by him on istimrari† tenure.

* Government of India to Colonel Ochterlony, 15th May 1813.

† On fixed rates.

These Jagirs, which were situated in the midst of British territory, had been placed under efficient police supervision in 1810, the inhabitants of the Karnal pargannah having at that time a bad reputation for violence and lawlessness.*

It was decided by the Government that these grants were merely life grants, and should be resumed at the death of Bhag Singh; and, moreover, that the provision made for Partab Singh was so ample, that he was not entitled to any new grant either in land or money on account of those resumed.†

The estate held in co-parcenary with Bhai Lal Singh:

With regard to the estate held, in co-parcenary with Bhai Lal Singh, it was clear that it was not intended to be granted for their joint lives, with benefit of survivorship, nor indeed, did this appear to be the view of the Chiefs themselves, and the Raja's share was consequently resumed on his death.††

The helpless State of Raja Bhag Singh

Raja Bhag Singh lingered in a paralytic state for many months. His intellect did not appear to suffer very much, but he was practically incapable of business, and it became necessary to make arrangements for carrying on the administration of the State. At this time the family of the Raja consisted of three sons and two wives. Fatah Singh, the eldest son, was Separated from his father who had a dislike to him, and it was thus almost impossible for him to act as Regent during

* Resident Delhi to Mr. Fraser 30th January 1810.

† Resident Dehli to Government of India, 18th June 1813. Government of India to Resident, 9th July 1818.

†† Sir D. Ochterlony to Government, 16th July 1817. Government to Sir D. Ochterlony 9th July 1818.

the Raja's illness. The second son, Partab Singh, whom the Raja desired to succeed him, had been declared by the British Government incompetent for succession, and it was manifestly undesirable to entrust him with even temporary power. The third son, Mehtab Singh, was still very young. The objection to the Regency of the eldest son applied equally to that of his mother, who was also disliked by the Raja and lived separate from him on a portion of the territory assigned for her maintenance. The mother of Partab Singh had long been dead, and Rani Sobrahi, the mother of Mehtab Singh, seemed the person against whose appointment as Regent the fewest objections could be urged. The Raja was not opposed to this arrangement and the Ministers desired it.

Rani Sobrahi appointed Regent AD 1814:

This lady was, accordingly, with the sanction of Government, appointed Regent. She engaged to respect and advance the wishes of the British Government with regard to the succession, and to abstain from any interference with the eldest son or his mother, who were to be permitted to resided on their estates, without molestation, during the remainder of the reign of Raja Bhag Singh.* Sir David Ochterlony was directed to proceed to Jhind, and himself superintend the new arrangements.† The Rani was installed in the presence of the Raja, Bhai Lal Singh, and all the confidential servants of the State, and the Raja, by most unmistakable signs, showed his full concurrence in the measure.††

* Resident to Secretary to Government 28th November. Resident to Colonel Ochterlony, 29th November. Colonel Ochterlony to Resident 15th October, and Government to Resident 23rd December 1813.

† Resident to Sir D. Ochterlony, 2nd February 1814.

†† Sir D. Ochterlony to Resident 29th August 1814. Government to Resident 4th March 1814.

The dissatisfaction of Prince Partab Singh:

But Prince Partab Singh was thoroughly dissatisfied. He had for long believed that on the death of his father the power would become his, and the present arrangements convinced him that he was intended to be excluded. He intrigued against the Regent, raised troops secretly, and, in June 1814, the Rani wrote that there could be no doubt that he meditated rebellion and that her life was no longer safe. The Prince was warned that the consequence of rebellion would be only to lose him the provision which would otherwise be made for him, and that he could not hope successfully to oppose the measures which had been determined on by Government.

He rebels, captures Jhind, and murders the Regent:

But, he would accept no warming, and, on the 23rd of August, took the fort of Jhind by surprise, and put to death the Rani, Munshi Jaishi Ram her principal adviser, the Commandant of the Fort, and many other persons.*

The action of the British authorities:

The Agent of the Governor General at once wrote to the officer in command at Karnal to hold himself in readiness to march at once to Jhind, on receipt of orders from the Resident of of Dehli, and the force at Hansi was also directed to move to Jhind, if the Prince, as anticipated, should attempt resistance. Sir Charles Metcalfe, the Resident, took instant action, and issued the following memorandum of instructions for the re-establishment of a legitimate Government at Jhind.†

* Sir D. Ochterlony to Government 3rd July 1814, and 24th August 1814.

† Sir D. Ochterlony to Lient Colonel Thompson, Commanding at Karnal, 26th August 1814, and to Sir C. Metcalfe of same date.

The memorandum of instruction for the re-establishment of a legitimate Government at Jhind:

" In consequence of the imbecility of Raja Bhag Singh, a provisional Government was lately established at Jhind under the authority of His Excellency the Governor General in Council. The Rani Sobrahi was placed in the management of affairs, though the Government was carried on in the name of the Raja as before.

“This arrangement was at the time judged most advisable for several reasons.

“The Raja's eldest son and lawful successor was not appointed to the management of affairs because he was known to be obnoxious to the Raja. A similar reason operated against the appointment of the Rani, the mother of the eldest son.

" The Raja's second son could not be appointed because it was known that the Raja wished to establish the succession in favor of the second son to the exclusion of the eldest. The same consideration would have prevailed against the Rani, the mother of the second son, had she been living.

" Rani Sobrahi, the mother of a third son, a youth since dead, from whose claims no apprehensions were entertained, was appointed to the Regency, under the idea that this arrangement united a sufficient degree of security for the succession of the eldest son, with a suitably degree of attention to the feelings of the Raja, more than any other that could be adopted.

" The second son, Kour Partab Singh, has now murdered the Rani, and her Chief Minister, and the Commandant of the Fort of Jhind and others.

He has obtained possession of the fort, and has usurped the Government.

" The Raja has been an unresisting or a willing instrument in the hands of Kour Partab Singh in these atrocious transactions.

“It is now necessary to subvert the usurped authority of Kour Partab Singh, and to re-establish a legitimate Government under the protection of the British Power,

" The following arrangements are therefore to be effected : —

" 1st. Kour Fatah Singh, the eldest son of Raja Bhag Singh, to be appointed to the entire management of affairs ; but the Government to be carried on in the name of his father the Raja.

“2nd. Suitable arrangements to be made for the dignity and comfort of the Raja, who, in every respect but the exercise of power with which he is not to be trusted, is to be considered and treated as heretofore.

“ 3rd. Kour Partab Singh, and the most notorious of his accomplices in the late murders, to be seized and sent in confinement to Dehli to await the orders of His Excellency the Governor General.

“It is most desirable that these arrangements should be accomplished without opposition, but if opposition be attempted, it must be defeated by the most prompt, decisive and energetic measures.

“Raja Bhag Singh, the eldest son Kour Fatah Singh, and the second son Kour Partab Singh, will be severally desired to wait on Colonel Arnold and Mr. Fraser. All the officers of the Jhind Government, Civil and Military, will also be ordered to put

" themselves under the orders of Colonel Arnold and " Mr. Fraser. I fall these requisitions be complied with, the arrangements prescribed will probably be carried into full effect without resistance.

“Kour Fatah Singh resides on his own estate at a distance from Jhind, and to that circumstance is probably indebted for his safety during the late murders. He will no doubt attend in conformity to the summons, and will also be directed to collect his adherents.

" The conduct of the Raja may probably depend on the will of Partab Singh, and may, therefore, as well as that of Partab Singh's be considered doubtful. Yet if there are about the Raja's person any Of those Councilors who have advised him hitherto during his connection with the British Government, it is to be expected that he will comply with the requisition, and submit without resistance to the arrangements prescribed.

" It is even possible that Partab Singh may do the same, though it is perhaps more probable that he will either determine to resist or endeavour to effect his escape.

" In the former case his opposition must be overcome by the most decisive measures, as before mentioned, whether it be supported or disavowed by the Raja. In the latter case the escape of Partab Singh will facilitate the unresisted accomplishment of the arrangements in view, but every exertion must be made to apprehend him and his accomplices.

“It has already been stated that Kour Fatah Singh is obnoxious to the Raja. It is therefore to be apprehended that the Raja will never be reconciled to the Regency of Fatah Singh. The most

“desirable arrangement is that the Raja should be reconciled to the eldest son, and should continue to reside at Jhind, and that Fatah Singh should treat the Raja with the utmost respect and attention. If this arrangement be impracticable owing to the Raja's strong aversion for his eldest son, the Raja may in that case be allowed to choose another place of residence, and such arrangement, as may be requisite can afterwards be adopted to make the remainder of his life easy and comfortable.

" It will be advisable to recommend Fatah Singh to employ in the transaction of the affairs of his Government the the old and faithful servants of his family, accustomed to business against whom there may not be any objection founded on participation in the recent atrocities.

" The utmost promptitude in the execution of the arrangements proposed is desirable. A detachment should advance at soon as possible to Jhind. No time should be lost in negotiation. But the first appearance of an inclination to resist should be followed on our part by the most decisive measures, consistent with the maxims of military prudence, on which point Colonel Arnold will be the sole judge.

" All the arrangements prescribed are of course to be understood to be subject to the revision of His Excellency the Governor General."

The Prince tries to implicate Raja in the murder:

An attempt was made by Partab Singh to persuade the world that the murder of Munshi Jaishi Ram and the Rani had been directed by the Raja himself, and was the punishment for, an intrigue which dishonored the family, but of this

there was no shadow of proof, and the fact of so many other persons interested in the continuance of the Regency being murdered at the same time sufficiently explained the reasons for the crime.

Pratab Singh flies from Jhind to Balawali

Prince Fatah Singh now took charge of the administration, and Partab Singh, knowing that British troops were marching from all sides against him, left Jhind and retired to Balawali, a fort in the wild country about Bhatinda. The zemindars of Balawali were a turbulent race, and Partab Singh had no difficulty in persuading them to adopt his cause. But he was at once followed by several troops of English cavalry who were directed to surround Balawali and prevent Partab Singh's escape, until a force, composed of five companies of infantry and three guns, which marched from Ludhiana on the 30th September, should arrive.

Then he crossed the Satlej and Joins Phula Singh Akali:

The Prince saw that it was dangerous to remain at Balawali, where his capture Was Certain, and, the day after he had entered the fort, he abandoned it, carrying off fifteen or twenty thousand rupees with other valuables that had been lodged there ; and after a long and circuitous march, crossed the Satlej at Makhowal, with forty followers, and joined Phula Singh Akali who was in force on the opposite bank.*

This famous outlaw † had taken up his residence at Nandpur Makhowal and defied the whole power of the Sikhs to expel him. He had with

* Sir D. Ochterlony to Resident Dehli 30th September 1814. Sir G. Clerk to Agent Governor General 20th March 1836.

† Phula Singh was the leader of the Akalis of the Amritsar temple, who attacked Mr. Metcalfe’s party in 1809, and also Lieutenant

him about seven hundred horse and two guns. With this man Partab Singh remained for two months, then persuading him to cross the Satlej and actively assist him at Balawali, which remained in open rebellion against the Raja of Jhind. When it became known that Phula Singh had crossed the Satlej, the Agent at Ludhiana wrote without delay to Raja Jaswant Singh of Nabha and the Khans of Maler Kotla, directing them to combine their forces and attack him, though such was the veneration in which Phula Singh was held by the Sikhs that there appeared little chance of the Nabha troops loyally acting against him, and Maler Kotla was not sufficiently strong to act alone.*

Partab Singh reaches Balawali, but Phula Singh compelled to retire:

Balawali, at this time, was invested by Pattiala troops, and was almost pared to Surrender, when its defenders heard of the approach of Phula Singh. They at once broke off negotiations, while Partab Singh went in advance and with a few men threw himself into the fort. Seven hundred of the Pattiala troops marched to intercept Phula Singh, who was unable to relieve the fort, and retired

While on survey duty, and, who, for his numerous crimes, had been outlawed by Ranjit Singh on demand of the British Government.

Vide ante p. 128, 132—84.

* Phula Singh had, as an Akali, (a Sikh ascetic class), great influence with his countrymen. The Maharaja tried for years, with half sincerity to capture him, and the English drove him from place to place, but could never seize him. At this very time, when Partab Singh joined him at Makhowal, the Maharaja had sent the most positive orders for the Philor troops to drive him out of his territories. The garrison was accordingly marched against him, but when they approached, Phula Singh sent to ask them if they would kill their Guru, (spiritual teacher). The Sikhs would not molest him ; and the whole force was kept out some two months to prevent his plundering, marching where be marched, more like a guard of honor than anything else. Numberless stories of the same kind can be told of Phula Singh, who was a very remarkable man. He was a robber and an outlaw, but he was nevertheless a splendid soldier, and a brave, enthusiastic man. He made friends with Ranjit Singh later, and won for him the great battle of Teri, in which he was killed, in 1823.

toward the Satlej, taking refuge in a village belonging to two Sirdars, Dip Singh and Bir Singh, who reproached the troops for attempting to offer violence to a poor fakir and their Guru. The Pattiala General did not know what to do in this emergency, and wrote to the Political Agent, who warned the Sirdars against protecting an outlaw whom all the Cis-Satlej Chiefs had been ordered to expel from their territories. The Chiefs of Nabha and Kythal were directed to send their forces to Balawali to co-operate with those of Pattiala, as the latter were afraid of the odium that would ever afterwards attach itself to them should they be the only assailants of Prince Partab Singh.

The fort of Balawali at last surrendered and Pratap Singh taken prisoner:

The Pattiala authorities wished a British force to be sent to Balawali, but this was unnecessary, for the garrison was reduced to great straits and the fort surrendered on the 28th of January. Prince Partab Singh was taken prisoner, but was placed under merely nominal restraint, and declared his intention of proceeding to Dehli to throw himself on the protection of the British Government. His ally, Phula Singh, was more fortunate. He marched to Mokatsar, in the Firozpur district, and there levied contributions, and being joined by Sirdar Nihal Singh Attariwala, gave battle to the Philor garrison, which he defeated with a loss of three hundred killed and wounded, the Akali not losing more than fifty men. The Maharaja was much annoyed at this affair, and thinking Phula Singh might be made useful if he took him into his service, invited him to Lahore, where he declined to go, demanding that Mokatsar, which was a sacred place of pilgrimage

among the Sikhs, should be given him for his residence.*

Pratap Singh seeks an asylum at Lahore in vain:

Pratab Singh fled to Lahore, but Maharaja Ranjit Singh refused to shelter a murderer, and gave him up to the English authorities who placed him in confinement at Dehli.

His death at Delhi AD 1816:

He died at Delhi in June 1816, and the estate of Barwana, which was granted in his name, lapsed to Government.† Partab Singh married two wives, Bhagbari, the daughter of Kirpal Singh of Shamghar, and the daughter of Sadha Singh, Kakar of Philor, but neither bore him any children.

Death of Prince Mehtab Singh:

His younger brother, Mehtab Singh, died a few mouths before him, when only sixteen years of age.

Prince Fatah Singh as Regent:

The administration of Jhind was now carried with tolerable tranquility. Prince Fatah Singh acting as Regent, and Raja Bhag Singh haying no other son, did not oppose an arrangement which was nevertheless distasteful to him.

The disputes regarding the villages Dabri and Danauli: