Parshu

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

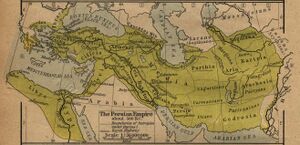

Parshu (पर्शु) was an ancient republic of Ayudhjivi Sangha known to Panini (V.3.117) and mentioned as Parshva (पार्श्व) in Mahabharata (VI.10.54). Persis is mentioned by Arrian[1] and Pliny[2].Persis was more properly a portion only or province of the ancient kingdom of Persia. It gave name to the extensive Medo-Persian kingdom under Cyrus, the founder of the Persian empire, B.C. 559.[3]

Variants of name

- Parsā (Old-Persian form Parsā as given in Behistun Inscription)

- Parshava/Parsava/Pārśava (a single member)

- Parshvah/Pārśavaḥ (whole tribe)

- Parshva (पार्श्व) Mahabharata (VI.10.54)

- Parśu

- Parsu

- Par-su (Babylonian form)

- Parsa/Pārsa/Pârsa (Persian)

- Par-sa-a-a (Babylonian)

- Sparsus (Baudhayana)

- Persis (Arrian Anabasis Book/6b,ch.xxviii)

- Persis (Pliny.vi.28, Pliny.vi.31)

- Persæ (Pliny.vi.29, Pliny.vi.39)

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Parsane = Persis (Pliny.vi.28)

- Parswal = Persis (Pliny.vi.28)

- Parswan = Persis (Pliny.vi.28)

Mention by Panini

Parshu (पर्शु) is mentioned by Panini in Ashtadhyayi. [4]

Parsava (पार्शव) is mentioned by Panini in Ashtadhyayi. [5]

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[6] mentions The Persian And The Arabian Gulfs. ....Here Persis begins, at the river Oratis13, which separates it from Elymais.14 Opposite to the coast of Persis, are the islands of Psilos, Cassandra, and Aracia, the last sacred to Neptune15, and containing a mountain of great height. Persis16 itself, looking towards the west, has a line of coast five hundred and fifty miles in length; it is a country opulent even to luxury, but has long since changed its name for that of "Parthia."17 I shall now devote a few words to the Parthian empire.

13 Now the Tab, falling into the Persian Gulf.

14 A district of Susiana, extending from the river Euleus on the west, to the Oratis on the east, deriving its name perhaps from the Elymæi, or Elymi, a warlike people found in the mountains of Greater Media. In the Old Testament this country is called Elam.

15 Ptolemy says that this last bore the name of "Alexander's Island."

16 Persis was more properly a portion only or province of the ancient kingdom of Persia. It gave name to the extensive Medo-Persian kingdom under Cyrus, the founder of the Persian empire, B.C. B.C. 559.

17 The Parthi originally inhabited the country south-east of the Caspian, now Khorassan. Under Arsaces and his descendants, Persis and the other provinces of ancient Persia became absorbed in the great Parthian empire. Parthia, with the Chorasmii, Sogdii, and Arii, formed the sixteenth satrapy under the Persian empire. See c. 16 of this Book.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[7] mentions ....It is requisite in this place to trace the localities of the Medi also, and to describe in succession the features of the country as far as the Persian Sea, in order that the account which follows may be the better understood. Media8 lies crosswise to the west, and so presenting itself obliquely to Parthia, closes the entrance of both kingdoms9 into which it is divided. It has, then, on the east, the Caspii and the Parthi; on the south, Sittacene, Susiane, and Persis; on the west, Adsiabene; and on the north, Armenia. The Persæ have always inhabited the shores of the Red Sea, for which reason it has received the name of the Persian Gulf. This maritime region of Persis has the name of Ciribo10; on the side on which it runs up to that of the Medi, there is a place known by the name of Climax Megale,11 where the mountains are ascended by a steep flight of stairs, and so afford a narrow passage which leads to Persepolis12, the former capital of the kingdom, destroyed by Alexander. It has also, at its extreme frontier, Laodicea13, founded by Antiochus.

8 Media occupied the extreme west of the great table-land of the modern Iran. It corresponded very nearly to the modern province of Irak-Ajemi.

9 The Upper and the Lower, as already mentioned.

10 Hardouin suggests that this should be Syrtibolos. His reasons for so thinking will be found alluded to in a note to c. 31. See p. 80, Note 98.

11 Or the "Great Ladder." The Baron de Bode states, in his Travels in Luristan and Arabistan, that he discovered the remains of a gigantic causeway, in which he had no difficulty in recognizing one of the most ancient and most mysterious monuments of the East. This causeway, which at the present day bears the name of Jaddehi-Atabeg, or the "road of the Atabegs," was looked upon by several historians as one of the wonders of the world, who gave it the name of the Climax Megale or "Great Ladder." At the time even of Alexander the Great the name of its constructor was unknown.

12 Which was rebuilt after it was burnt by Alexander, and in the middle ages had the name of Istakhar; it is now called Takhti Jemsheed, the throne of Jemsheed, or Chil-Minar, the Forty Pillars. Its foundation is sometimes ascribed to Cyrus the Great, but more generally to his son, Cambyses. The ruins of this place are very extensive.

13 Its site is unknown; but Dupinet translates it the "city of Lor."

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[8] mentions The Tigris....The country on the banks of the Tigris is called Parapotamia19; we have already made mention of Mesene, one of its districts. Dabithac20 is a town there, adjoining to which is the district of Chalonitis, with the city of Ctesiphon21, famous, not only for its palm-groves, but for its olives, fruits, and other shrubs. Mount Zagrus22 reaches as far as this district, and extends from Armenia between the Medi and the Adiabeni, above Parætacene and Persis. Chalonitis23 is distant from Persis three hundred and eighty miles; some writers say that by the shortest route it is the same distance from Assyria and the Caspian Sea.

19 Or the country "by the river."

20 Pliny is the only writer who makes mention of this place. Parisot is of opinion that it is represented by the modern Digil-Ab, on the Tigris, and suggests that Digilath may be the correct reading.

21 Mentioned in the last Chapter.

22 Now called the Mountains of Luristan.

23 The name of the district of Chalonitis is supposed to be still preserved in that of the river of Holwan. Pliny is thought, however, to have been mistaken in placing the district on the river Tigris, as it lay to the east of it, and close to the mountains.

History

V. S. Agrawala[9] mentions Sanghas known to Panini which includes - Parshu (पर्शु), under Parshvadi (पर्शवादि) (V.3.117).

V. S. Agrawala[10] mentions the names of Ayudhjivi Sanghas in the Panini's Sutras which include Parśu (V.3.117) – The whole tribe was called Pārśavaḥ, and a single member Pārśava. The Parshus may be identified with the Persians. The Parsus are also known to Vedic literature (Rigveda, VIII.6.46) where Ludwig and Weber identify them with the Persians. Keith discussing Panini’s reference to the Parsus proposes the same identification and thinks ‘that the Indians and Iranians were early connected’. Gandhara; Panini’s homeland, and Pārsa, both occur as

p.446: names of two provinces in the Behustun Inscription, brought under the common sovereignty of Darius (521-586 BC), which promoted their mutual intercourse. Panini knows Gāndhāri as Kingdom (IV.1.169). It seems that soon after the death of Darius Gandhara became independent, as would appear from the manner of its mention by Panini as an independent Janapada. Panini’s Pārśava is nearer to the old Persian form Parsa (cf. The Behistun Inscription) denoting both the country and its inhabitants, and the king Darius calls himself as Pārsa, Pārshahyā pusa, ‘Persian, son of Persian’ (Susa Inscription, JAOS, 51.222).

Baudhayana also mentions the Gandharis along with the Sparsus among western peoples.

Panini and the Parsus

V. S. Agrawala[11] writes that [p.466]: Panini refers to a people called Parsus as a military community (Ayudhjivi Sangha, V.3.117). The Parśu corresponds to to the Old-Persian form Parsā as given in Behistun Inscription. The Babylonian form

[p.467]: of the name in the same Inscription is Par-su which comes closer to Panini’s Parśu (Behistun Inscription, British Museum,pp.159-166). It appears that Parsu was the name of a country as noted in the Babylonian version, and Pārśava was designation of an individual member of that Sangha, a form of the name which corresponds to Babylonian Par-sa-a-a. A part of India was already a province of Achaemenian empire under Cyrus and Darius, which it enriched with its military and material resources. Indians were already serving in the army of Xerxes and fighting his battles about 487 BC, while that very small part of India paid as much revenue as the total revenue of the Persian Empire. There was thus an intimate inter-course between north-west India and Persia, and Panini as one born in that region must have had direct knowledge of such intercourse.

Parsu are Persians

Parsus are considered to be Persians by Dr. Buddha Prakash.[12][13]

The Parsus have been connected with the Persian people, though this view is disputed by some.[14] This is based on the evidence of an Assyrian inscription from 844 BC referring to the Pesians as Parsu, and the Behistun Inscription of Darius I of Persia referring to Parsa as the origin of the Persians.[15]

In Mahabharata

Bhisma Parva, Mahabharata/Book VI Chapter 10 describes geography and provinces of Bharatavarsha. Parshva (पार्श्व) is included in the list of provinces in verse (VI.10.54). [16]

Jat History

Bhim Singh Dahiya[17] gives details about a Rigvedic tribe named Parsu : (RV X/86/23, Vlll/6/48) Parsava (1/105/8). A great donor King named Tirindira of this clan is mentioned in RV Vlll/6/46. Prithu Parsva, the great donor king is mentioned in Vlll/6/46. They are to be identified with Parsval clan of the Jats; gave their name, Pars, Persia to Iran. They are also mentioned by Panini (V/3/117).

Bhim Singh Dahiya[18] tells....The Parsvah of Panini are the modern Parsawal Jats. V.S. Agarwala quotes Rig Veda (VIII, 6, 46) to show that they were known at that time also.[19] His identification of Paravah with the Persians may well be correct but it only shows the long association of the Parswal Jats with Iran.

Bhim Singh Dahiya[20] has provided us Clan Identification Chart:

| Sl | West Asian/Iranian | Greek | Chinese | Central Asian | Indian | Present name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 113. | Parsua | - | - | - | Parsava | Parswal |

Ch 6.29: Alexander in Persis — tomb of Cyrus repaired

Arrian[21] writes.... He himself then marched to Pasargadae in Persis, with the lightest of his infantry, the Companion cavalry and a part of the archers; but he sent Stasanor down to his own land.[1] When he arrived at the confines of Persis, he found that Phrasaortes was no longer viceroy, for he happened to have died of disease while Alexander was still in India. Orxines was managing the affairs of the country, not because he had been appointed ruler by Alexander, but because he thought it his duty to keep Persia in order for him, as there was no other ruler.[2] Atropates, the viceroy of Media, also came to Pasargadae, bringing Baryaxes, a Mede, under arrest, because he had assumed the upright head-dress and called himself king of the Persians and Medes.[3] With Baryaxes he also brought those who had taken part with him in the attempted revolution and revolt. Alexander put these men to death. He was grieved by the outrage committed upon the tomb of Cyrus, son of Cambyses; for according to Aristobulus, he found it dug through and pillaged. The tomb of the famous Cyrus was in the royal park at Pasargadae, and around it a grove of all kinds of trees had been planted. It was also watered by a stream, and high grass grew in the meadow. The base of the tomb itself had been made of squared stone in the form of a rectangle. Above there was a stone building surmounted by a roof, with a door leading within, so narrow that even a small man could with difficulty enter, after suffering much discomfort.[4] In the building,lay a golden coffin, in which the body of Cyrus had been buried, and by the side of the coffin was a couch, the feet of which were of gold wrought with the hammer. A carpet of Babylonian tapestry with purple rugs formed the bedding upon it were also a Median coat with sleeves and other tunics of Babylonian manufacture. Aristobulus adds that Median trousers and robes dyed the colour of hyacinth were also lying upon it, as well as others of purple and various other colours; moreover there were collars, sabres, and earrings of gold and precious stones soldered together, and near them stood a table. On the middle of the couch lay the coffin[5] which contained the body of Cyrus. Within the enclosure, near the ascent leading to the tomb, there was a small house built for the Magians who guarded the tomb; a duty which they had discharged ever since the time of Cambyses, son of Cyrus, son succeeding father as guard. To these men a sheep and specified quantities of wheaten flour and wine were given daily by the king; and a horse once a month as a sacrifice to Cyrus. Upon the tomb an inscription in Persian letters had been placed, which bore the following meaning in the Persian language:

- " man, I am Cyrus, son of Cambyses, who founded the empire of the Persians, and was king of Asia. Do not therefore grudge me this monument."

As soon as Alexander had conquered Persia, he was very desirous of entering the tomb of Cyrus; but he found that everything else had been carried off except the coffin and couch. They had even maltreated the king's body; for they had torn off the lid of the coffin and cast out the corpse. They had tried to make the coffin itself of smaller bulk and thus more portable, by cutting part of it off and crushing part of it up, but as their efforts did not succeed, they departed, leaving the coffin in that state. Aristobulus says that he was himself commissioned by Alexander to restore the tomb for Cyrus, to put in the coffin the parts of the body still preserved, to put the lid on, and to restore the parts of the coffin which had been, defaced. Moreover he was instructed to stretch the couch tight with bands, and to deposit all the other things which used to lie there for ornament, both resembling the former ones and of the same number. He was ordered also to do away with the door, building part of it up with stone and plastering part of it over with cement and finally to put the royal seal upon the cement. Alexander arrested the Magians who were the guards of the tomb, and put them to the torture to make them confess who had done the deed; but in spite of the torture they confessed nothing either about themselves or any other person. In no other way were they proved to have been privy to the deed; they were therefore released by Alexander.[6]

1. Aria. See chap. 27 supra.

2. Curtius (x. 4) says Orxines was descended from Cyrus.

3. See iii. 25 supra.

4. Cf. Strabo, xv. 3, where a description of this tomb is given, derived from Onesioritus, the pilot of Alexander. See Dean Blakesley's note on Herodiotus i. 214.

5. Just a few lines above, Arrian says that the couch was by the side of the coffin.

6. Cf. Ammianus, xxiii. 6, 32, 33. The Magi were the priests of the religion of Zoroaster, which was professed by the Medes and Persians. Their Bible was the Avesta, originally consisting of twenty-one books, only one of which, the twentieth (Vendidad), is still extant.

पर्शुस्थान

विजयेन्द्र कुमार माथुर[22] ने लेख किया है ...पर्शुस्थान (AS, p.534) पर्शु नामक एक युयुत्सु जाति का पाणिनि ने ने उल्लेख किया है (अष्टाध्याई 5,3,117) जो भारत के उत्तर पश्चिम के प्रदेश में, संभवत है काबुल के निकटवर्ती भूभाग में निवास करती थी. पर्शुस्थान इन्हीं के देश का नाम था. यहीं अलसंदा की स्थिति थी. पर्शु या पार्शव का संबंध पारस या ईरान देश से भी हो सकता है. (देखें अलसंदा)

External links

See also

References

- ↑ Arrian Anabasis Book/6b,ch.xxviii

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 28

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 28, fn.16

- ↑ V. S. Agrawala: India as Known to Panini, 1953, p.445, 446, 467

- ↑ V. S. Agrawala: India as Known to Panini, 1953, p. 446, 467

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 28

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 29

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 31

- ↑ V. S. Agrawala: India as Known to Panini, 1953, p.500

- ↑ V. S. Agrawala: India as Known to Panini, 1953, p.445-446

- ↑ V. S. Agrawala: India as Known to Panini, 1953, p.466-467

- ↑ Political and Social Movements in Ancient Punjab, p. 103

- ↑ Tej Ram Sharma: Personal and geographical names in the Gupta inscriptions/Tribes,p.173

- ↑ A. A. Macdonell and A. B. Keith (1912). Vedic Index of Names and Subjects.

- ↑ Radhakumud Mookerji (1988). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times (p. 23). Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 8120804058.

- ↑ वध्राः करीषकाश चापि कुलिन्दॊपत्यकास तदा, वनायवॊ दशा पार्श्वा रॊमाणः कुश बिन्दवः (Mahabharata,VI.10.54)

- ↑ "Aryan Tribes and the Rig Veda". (1991) Dahinam Publishers, 16 B Sujan Singh Park, Sonepat, Haryana, India.

- ↑ Jats the Ancient Rulers (A clan study)/The Jats,p.73

- ↑ Rig Veda, VIII. 6,46

- ↑ Jats the Ancient Rulers (A clan study)/Appendices/Appendix II,p. 325, S.No.113

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/6b, Ch.29

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.534

Back to Mahabharata People